Orion (Lacoste)

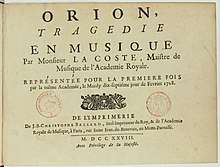

Orion is an opera by the French composer Louis Lacoste on a libretto by Joseph de Lafont and Simon-Joseph Pellegrin. It was first performed at the Paris Opera (at the time known as "Académie royale de Musique") on 19 February 1728[1] and was performed for the last time on 12 March 1728.[2] The reduced score was printed in quarto by Christophe Ballard and is today available for consulting on the website of the Bibliothèque nationale de France. Orion only received a modest success and was never staged nor performed again for another season. However, extracts have already been played by the ensemble Fuoco e Cenere in 2019.[3]

| Orion | |

|---|---|

| tragédie en musique by Louis de La Coste | |

Title page of the reduced score | |

| Librettist | Joseph de La Font, Simon-Joseph Pellegrin |

| Language | French |

| Based on | Orion (mythology) |

| Premiere | 19 February 1728 Académie royale de musique |

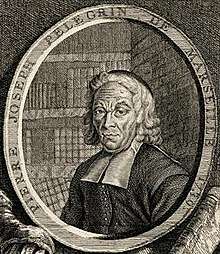

A libretto by La Font, Hypermnestre, won considerable success in 1716 with the music of Charles-Hubert Gervais. Pellegrin has made himself known in 1713 with the tragédie lyrique Médée & Jason (music by François-Joseph Salomon) but his most brilliant success would be Jephté in 1732 (music by Michel Pignolet de Montéclair), followed by Hippolyte & Aricie in 1733 (music by Jean-Philippe Rameau). La Font died in 1725 before the completion of Orion's libretto, which Pellegrin took care of. It was the second and final collaboration between Lacoste and Pellegrin, the first was Télégone (1725).[4]

Mythology

The plot is based on the ancient myth of Orion. A son of Neptune and Euryale, daughter of Minos, he was born in Boeotia. This handsome giant was on the island of Chios when he fell in love with Merope, daughter of Oenopion. That king promised her to him in condition that he gets rid of the wildlife from his island. Orion fullfilled the request but the king rejects his promise. Thus, Orion tried one night to rape Merope and was punished by her father by being blinded. It was only thanks to the blacksmith Cedalion that Orion regained his sight.

The goddess Diana managed to convince him to become her hunting partner. Apollo, fearing that his chaste sister might fall in love with Orion, sent a monstruous scorpion to kill him. Orion plunged into the sea to swim to Delos. However, Apollo designated the swimming giant to Diana as Candaon, a wicked monster who seduced Opis, one of her hyperborean nymphs. Unbeknownst to the goddess, Candaon was Orion's name in Boeotia and so she struck him down with one of her arrows.

When she realised what she's done, Diana implored the gods to revive Orion. Jupiter, unfazed by her wish, torched his body with lightning before he could be resuscitated. Thus, Orion was placed among the stars as a constellation. In other versions of the myth, he was killed due to either loving Diana or trying to rape Opis.

Before Lacoste's Orion, this myth was already adapted to the opera genre. Known examples include Francesco Cavalli's dramma per musica L'Orione (1653), Christian Ludwig Boxberg's Orion (1697) and Gottfried Heinrich Stölzel's Orion (1713).

Cast

Singing roles

| Characters | Voice type | Premiere, 19 February 1728 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Venus | Dessus[5] (Soprano) | Julie Eeremans | |

| Jupiter | Basse-taille[6] (Bass-baritone) | Claude-Louis-Dominique de Chassé de Chinais | |

| Minerva | Dessus[7] | Françoise Antier[8] | |

| Cupid | Dessus[9] | Mlle Julie | |

| A Follower of Minerva | Dessus[10] | Anne Mignier | |

| Diana | Dessus[11] | Marie Antier | |

| Orion, Son of Neptune | Haute-contre[12] (Tenor with mixed voice) | Denis-François Tribou | |

| Pallantus, King of the Scythians | Basse-taille[13] | Claude-Louis-Dominique de Chassé de Chinais | |

| Alphisa, Daughter of Boreas; Nymph of Diana | Dessus[14] | Marie Pélissier | |

| Palemon, Friend of Orion | Basse-taille[15] | Jean II Dun | |

| A Theban | Dessus[16] | Julie Eeremans | |

| Two Nymphs of Diana | Dessus[17] | Mlle Petitpas,[18] Anne Mignier | |

| A Scythian | Basse-taille[19] | Jean II Dun | |

| Aurora | Dessus[20] | Mlle Dun[21] | |

| Phosphorus | Dessus[22] | [23] | |

| Memnon (the Oracle) | Basse-taille[24] | [25] | |

| Hymen | Dessus[26] | [27] | |

Chorus

| Groups of Gods and Heroes, Arts, Lovers, Games, Pleasures, Graces, Chorus of Diana's Nymphs behind the stage | ||

| Groups of Theban Warriors, Diana's Nymphs, Scythians, Nymphs, Pastors and Thebans | ||

| Voice part | Côté du Roy | Côté de la Reine |

|---|---|---|

| Basse-taille | Jean I Dun,[28] Jacques Brémont, François Flamand | René-Jacques Lemire, Gérard Morand, Jacques Saint-Martin, Justin Destouches Dubourg.[29] |

| Taille (Low Tenor) | Levasseur (?), Oudart Duplessis, Combeau | Duchesne, Germain Houbeau |

| Haute-contre | Jacques Deshayes, Jean-Baptiste Buseau, Dubrieul | Bertin, Dautrep, Corail |

| Dessus | Souris-l’aînée, Julie, Dun, Souris-cadette, Dutillié, Anne-Marguerite-Marie de Kerkoffen | Françoise Antier, Claude Laroche, Marguerite Tettelette, Charlard, Petitpas, Marie-Claude-Nicole Cartou |

Dancers

| Characters | Premiere, 19 February 1728 |

|---|---|

| Graces | Marie-Madeleine Ménès, Mlle Duval, Jeanne-Éléonore Tiber, Marie Durocher |

| Pleasures | François-Louis Maltair, Mr Savar, Mr Tabary, Mlle Binet, Mlle la Martinière |

| Games | Antoine-François Botot Dangeville, Claude Javilliers, Mlle de Lisle, Anne-Catherine Cupis de Camargo[30] |

| Male Thebans | David Dumoulin,[31] Henri-Nicolas Dumoulin,[32] Mr Savar, Mr Tabary, Henry-François Pieret, Antoine Bandieri de Laval, François-Louis Maltair |

| Female Thebans | Mlle de Lisle, Marie-Antoinette Petit, Jeanne-Éléonore Tiber, Anne Lemaire, Mlle Verdun |

| Nymphs | Françoise Prévost, Mlle de Lisle, Mlle Duval, Marie-Antoinette Petit, Jeanne-Éléonore Tiber, Marie Durocher, Mlle Binet, Mlle la Martinière |

| Scythians | Michel Blondy, Antoine Bandieri de Laval, Marie-Anne de Camargo, Henri-Nicolas Dumoulin, Mr Savar, Henry-François Pieret, Pierre Dumoulin, Antoine-François Botot Dangeville, Ferdinand-Joseph Cupis de Camargo, Marie-Antoinette Petit, Marie Sallé, Jeanne-Éléonore Tiber, Marie Durocher, Mlle Binet, Mlle la Martinière |

| Pastors | François Dumoulin,[33] Pierre Dumoulin, Mr Picar, Antoine-François Botot Dangeville, François-Antoine Maltair |

| Nymphs | Marie-Anne de Camargo, Marie-Antoinette Petit, Marie Sallé, Jeanne-Éléonore Tiber, Marie Durocher, Mlle Binet, Mlle la Martinière |

| Thebans, Nymphs | N/A[34] |

Plot

Joseph de La Font left the libretto unfinished with its first three acts, to which Simon-Joseph Pellegrin added the prologue and the last two acts[35]. Lafont makes Orion a follower of Diana, who was banished from her presence after the hunter offended her with his love for her. He was pardoned by saving Alphisa (named "Opis" in the mythology), a nymph of Diana[36]. Orion and Alphisa love each other but Diana, this time in love with Orion, opposes to their union.

Prologue

The Theater represents the avenues of Cythera, where the Arts finish raising a Throne for Cupid

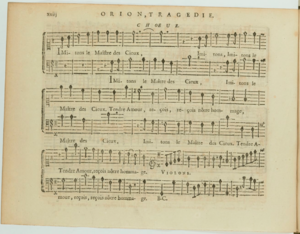

Venus calls for Lovers, Pleasures, Graces and Arts to honor Cupid (“Hâtez-vous, préparez ces lieux”) (1). Other deities descend, ballet for Jupiter and Cupid (2). Minerva approves that her followers be subjected to Love. Behind the theater, Diana's followers declare war on Cupid. Venus and her son swear revenge against Diana ("Que ce superbe cœur...") (3).

Act I

The Theater represents a Countryside, covered with Flowers; we see the Statue of Memnon, turned towards the East; The city of Thebes is revealed. Orion is lying on a bed of greenery in his Hunter outfit, his Bow & his Arrows at his feet.

Palemon discovers Orion agitated by a dream. Orion tells him that he saw in his dream his beloved nymph threatened by Diana ("Je goûtais le repos...") (1). Pallantus, from Scythia, enters and declares to Orion that he is in love with a nymph of Diane and that the goddess, forced by fate, must today grant her nymphs the opportunity to choose a husband. Orion tells him about his dream and informs him that the statue of Memnon, the son of Aurora, animated by the return of his mother, will shed light on their fate (2). Phosphorus comes with Thebans and asks them to pay homage to Memnon ("Joignez les Tambours"), ballet (3). Aurora descends and calls on the oracle of her son (4). Memnon informs Orion and Pallantus that one of them will be blessed with immortal glory and that the other one will perish (5).

Act II

The Theater represents a Forest.

Orion expresses heartwrenching horror in regards to the oracle of Memnon and the dream he made ("Pourquoi, faut-il, hélas !..."). The horns signal Diana's approach (1). Orion sees Alphisa, the nymph he met in his dream, looking for Diane with whom she is hunting a monster. The latter appears and attacks Alphisa but is defeated by Orion. The hunter declares his love for Alphisa but she rejjects him (2). Diana comes and discovers that Orion saved Alphisa. After the nymph has left, she gives thanks to him and invites her to celebrate her triumph ("J'ai triomphé d'un Monstre affreux"), ballet (3). Pallantus is seen by Diana. Orion explains that he has come to find the nymph that he adores. Pallantus then confesses to Diane that he would like to have the love of Alphisa. Orion is struck by this confession while Diane consents to his love (4).

Act III

The Theater represents the opening of the Nile: this River is surrounded by Rocks.

Alphisa who believes that Diana still disdains Orion, expresses her love for the latter despite her duty as a nymph ("Qu'ai-je entendu ?...") (1). Orion arrives and announces that "a King" loves her. The nymph reminds him of his former love for Diana and doubts that Orion can love her. She finally gives in and confesses her mutual love to him. Orion assures that Diana will be favorable to their union (2). Alphisa goes out. Orion, torn between friendship and love, decides to betray Pallantus. (3). Exit of Orion and entry of Diana. The troubled goddess feels subjected to the powers of Cupid ("Vas-tu m'abandonner...") (4). Alphisa enters. Diana confesses to the nymph that she is in love with a mortal and tells her that Orion has told her about her love for someone, which she is in favor of. Alphisa, believing that Diana wants to grant her Orion, accepts Diana's proposition. She is struck by surprise when she learns that it is Pallantus (5). Left alone, Alphisa has no doubt that the mortal that Diane loves is Orion and laments ("Objet de tous mes vœux...") (6). Pallantus arrives and tries to court the nymph (7). Scythian ballet for Alphisa. Alphisa goes out to join Diana. Pallantus informs her that a party is being prepared for their marriage (8).

Act IV

The Theater represents the Temple of Diana: We can see the attributes of the Goddess & those of Cupid, combined together: a Throne is raised in the middle.

Orion regrets having supported Pallantus' love while he prepares the marriage of his rival with Alphisa ("Que tu me fais souffrir...") (1). Alphisa enters, she informs him that Diana loves him. Orion is shocked and confesses to her that he helped Pallantus to confess his love. The two lovers hope that Cupid will be supportive of their forbidden relationship ("Vole, Amour, viens nous secourir") (2). Alphisa exits. Diana enters and announces to Orion that she is no longer opposed to his love. Orion pretends to not understand her. Offended, Diana orders him to go out whilst hiding her sadness (3). Alone, Diana laments Orion's indifference and suspects that she has a rival (“Fatal Auteur de mes alarmes") (4). Pallantus, Orion, shepherds and nymphs enter and celebrate the wedding organized by Diana, ballet. Alphisa refuses to marry Pallantus by saying that she wishes to stay with the goddess. Diana orders everyone to leave but retains Alphisa (5). She is not fooled and reveals to the nymph that she is aware of her love with Orion through the gazes that they exchanged during the party. Thus, she orders Alphisa to marry Pallantus or to be sacrificed ("Tremblez, l'Amour jaloux...") (6).

Act V

The Theater in the following Act represents the interior part of the Temple of Diana. We see there an erected Altar, on which we put on one side, the torch of the god Hymen; & on the other, a deadly knife.

Diana declares her revenge against Cupid and only lets Hatres fill her heart ("Amour, redoutable vainqueur") (1). Orion discovers the altar Alphisa's sacrifice. Diana swears to kill her and Orion swears to defy the goddess to save his beloved (2) ("Transports de haine & de rage"). Enter Alphisa and Pallantus. Diana orders the nymph to make her choice. Alphisa decides to kill herself but Pallantus snatches the knife from her and sacrifices himself (3). The goddess is horrified and touched by the death of Pallantus and thus realises her cruelty. She reunites Orion and Alphisa and renounces her unrequited love ("L'Amour m'a soumise à sa loi"). Alphisa honors the glory of Diana and Orion orders the Thebans to celebrate his triumph aswel as Diana and Cupid's (4). Ballet of Thebans and Nymphs. Diane calls on Hymen to descend (5). Hymen descends and the characters celebrate the wedding of Alphisa and Orion who receive their apotheosis as constellations in the sky (6).

Conditions of performance and critical reception

First scheduled for February 17 1728[37], the first performance of Orion at the Opera took place on February 19[38]. During the premiere, "the Assembly was very crowded and quite tumultuous." The theater was no less full during the performances that followed. However, they were quieter[39].

Orion finished its run on March 12 of the same year, after its fourteenth performance[40]. It was replaced with Bellérophon by Jean-Baptiste Lully. The Prince of Monaco Antoine Ier evoked the failure of Orion in a note addressed to the Marquis of Grimaldi: "It pleases me to hear from you that the actors of the Opera are patching things up, and that we will compensate the public for the failure of Orion with Bellérophon, since Lully is always needed in such an occasion."[41]

Music and libretto

Some vocal pieces were applauded, such as the duet between Orion and Alphisa ("Vole, Amour, viens nous secourir", Act IV, Scene 2)[42] and the one between Orion and Diana ("Transports de haine & de rage", Act V, Scene 2), which was “the greatest beauty” of the scene[43]. The scene 5 of Act III in which Diana reveals to Alphisa that she's in love with Orion was hailed as "one of the most well written" scenes of the opera[44].

The libretto by Lafont and Pellegrin received mixed reviews and two opposing camps were formed[45]. Their debate revolved around:

- The suddenly vengeful character of Diana in act IV, criticized by one party but justified by the other through the pain of love that Cupid imposes on her.

- The character of Pallantus, who was considered by one crowd to be too tender and gullible for a Scythian. The opposing crowd, however, argue that he is an example of how love can tame a savage. His hope that he'll receive Alphisa's mutual love is also justified through the suggestion that Diana may have assured him of the nymph's feelings.

Staging and choreography

The scenery of Act III had greatly pleased the spectators: The cascade which formed the fall of the Nile was "very ingeniously invented" and the sky, painted manually entirely by Giovanni Niccolò Servandoni, was highly applauded[46]. The decoration of the temple of Diana was already used in 1726 for the palace of Ninus in Pyrame & Thisbé by François Francœur and François Rebel. It was "more beautiful than ever"[47].

The ballet, choreographed by Louis Pécour (who died a year after Orion's performances), was much appreciated. The pas de trois danced by Marie-Anne de Camargo and her two colleagues Michel Blondy and Antoine Bandieri de Laval in act III were particularly noticed[48].

Literary analysis

Thematic

A durable tradition

Berain_Jean_btv1b52511001f_1.jpg)

Orion's libretto has a typical plot of a tragédie lyrique:

Two young protagonists love each other (Orion and Alphisa). However, they both have romantic rivals that act as obstacles to their romance (Diana and Pallantus), at least one of them is the main antagonist. This general structure is firmly established since the first operas of Lully, in particular:

- Thésée (1675), words by Philippe Quinault

- Atys (1676), words by Philippe Quinault

- Bellérophon (1679), words by Thomas Corneille and Bernard Le Bouyer de Fontenelle

It remains permanently in the repertoire after the death of Lully and Quinault, e.g.:

- Vénus & Adonis (1697), words by Jean-Baptiste Rousseau

- Idoménée (1712), words by Antoine Danchet

- Pirithoüs (1723), words by Jean-Louis Ignace de la Serre

We thus find in Orion recurring themes in previous libretti:

- The Sommeil (Sleep), as shown opposite in Atys (1676), also present in Circé (1694) and Alcyone (1706)

- The combat with a monster, also present in Cadmus & Hermione (1673) or Manto la Fée (1711)

The comparison with Atys

Orion owes much of its literary influence to Atys. It is even relevant to say that its main characters are based on those of Quinault:

- Orion/Atys, titular character, friend of the king:

- Pallantus/Celenus, who receives the agreement of the powerful goddess:

- Diana/Cybele, to marry the girl:

- Alphisa/Sangaride, however secret lover of her fiancee's confidant.

The goddess, once proud and indifferent in regards to love, also falls in love with the young man. But when she discovers that her feelings are not mutual, Diana decides to take revenge on her rival. The Mercure de France even noted a comparison between Dians and female antagonists of previous operas: Medea and Cybele[49].

Despite these great similarities, Orion can still be distinguished from Atys by:

- The unfolding of plot events:

- Orion and Alphisa, strangers until act II, only confirm their mutual love in act III, while Atys and Sangaride, childhood friends, confess theirs to each other in act I.

- By saving Alphisa, Orion, once rejected and banished by Diane, makes himself adored by her. On the other hand, Atys never had eyes for Cybele, who fell in love with him before the start of the opera.

- The celebratory ballet that forms the happy end of Orion is opposed to the tragic end of the two lovers in Atys.

- The absence of the some characteristic elements of the first tragedies:

- Instead of praising the French regent, the prologue announces the subject of the story.

- The confidants/servants and the secondary storylines, inherited from venetian operas, disappear or are reduced in favor of the main plot.

Adaptation of the myth

Torn between two registers

According to musicologist Cuthbert Girdlestone, the mixed reception of Orion was due to its dramatically inconsistent libretto: According to him, Simon-Joseph Pellegrin, who added the prologue and the acts IV and V to complete the work, combined hardly harmoniously his style and conception of the myth with Joseph de La Font's. For this, Girdlestone qualifies the subject as “without interest” and the structure as “very weak”[50]. The musicologist Thomas Leconte furthers this idea by qualifying the first three acts as light and more suitable for a pastorale héroïque[51]. Pellegrin's final acts, on the other hand, heighten the violence, where the inevitable loss of the young lovers can be felt.

The pastoral tone

The pastoral subject is recurring in french novels and poems between of the XVIth and the XVIIIth centuries, but was already present in medieval literature (e.g. The Game of Robin and Marion). Jean-Baptiste Lully's first opera also features the subject, by the insertion of secondary characters. It soon became the principal theme of an opera with the first pastorale héroïque: Acis & Galatée (1687). The mythological choice of Lafont gives this opera the touches of a typical pastorale héroïque:

- The giant Orion is often attached to the goddess of hunting Diana, whose followers are nymphs and shepherds who refuge in her woods.

- The pastoral name "Palemon" of Orion's confidant, is used for other shepherd characters from previous operas: Vénus & Adonis (1697) or Les Muses (1703).

- Although the character Pallantus is king, the plot of Orion always takes place in a rural context, relating to nature or to Diana: "a Campaign covered with flowers" (act I), "a wood" (act II, V ), "The mouth of the Nile" (act III), "the Temple of Diana" (act IV). Tragédie lyriques, however, take place within a kingdom and often contain a very strong political significance, e.g. Phaéton (1683), Théagène & Cariclée (1695) or Polyxène & Pyrrhus (1706).

The tragic tone

Until the end of act III, the opera is loaded with ballets and on the dramatic level, the characters evoke more the pains of love than the fatal dilemma of the work. The frightening vision of Orion and the deadly oracle of Memnon leave a less important trace in act I than the act's ballet and are rarely mentioned in acts II and III.

The fatal reminder only prominently comes back in act IV, during which the dialogue between the two lovers recalls the death of Orion or Pallantus and the violence of Diana. Then Diana, rejected by Orion, expresses her dilemma in "Fatal Auteur de mes alarmes" and, now the confirmed vilain of the story, unleashes her fury against Alphisa to complete act IV.

The act V amplifies the darkness of the plot with Diana's anger against Cupid and her confrontation with Orion. The scene of the sacrifice is more heartwrenching with Pallantus' death. Nevertheless, after Diana's remorse, the tragedy ends well with an end that brings the two young lovers together.

Dramatic treatment of the characters

Diana

The character of Diana, introduced only in the middle of act II, is undoubtedly the most complex character. A typical example of an enchantress in love, known as a "rôle de baguette" (wand role) (e.g. Armida, Circe, Alcina), the goddess goes through episodes during which her state of mind undergoes a clear evolution in all of its polarity. It is especially in the last two acts that the character of Diana is developed.

Diana's entry into act II acts as a trigger for the ballet, which depicts the "glory" and "victory" of the goddess. Recognized for her inflexible defense against love, Diana is in act III torn between her pride and her attraction to Orion. The virgin deity feels robbed from her heart "the innocent pleasures" which define her chastity. Despite her resistance, she lets herself be overcome and swept away by love when she confides her secret to Alphisa. In act IV, Diana, believing that Orion still loves her, is now confronted with his indifference. Her disappointment with this new dilemma grows to become fury when she discovers her rival. In the final act, Diana complains of the insulting torture which Cupid subjects her to. She finally gives in to her "motions of hate and rage" and only aspires to take revenge. Nevertheless, she lets herself be moved by the sacrifice of Pallantus. Thus, Diana recognizes her loss against Cupid but regains her honor by yielding Orion to her rival: "Love has triumphed over me; I triumph over Love itself".

Alphisa

The nymph Alphisa, like the goddess Diana, was not introduced until act II where her presence was brief. Nevertheless, Lafont devotes the majority of act III to develop her character through several states of mind. Pellegrin also gives her importance in act IV.

When she met Orion, Alphisa was not charmed by the young man. She did not remain insensitive for long after he courageously saved her. The nymph refused his advances, but secretly recognized in her the love that arises: "Alas! the more I see him, the more I fear to see him". In act III, love takes hold of her against her will. Alphisa finally her love to Orion but nevertheless fears Diana. When she discovers that the goddess too is in love, Alphisa tries to keep her cool when she thought that Diana was going to grant her Orion: "I can hardly accept him; But he must be dear to me when he comes from thee". Her mood changes when the ambiguity is clarified. In her poignant monologue which follows, she echoes the verse "Mon cœur trop plein de ce que j'aime" (My heart too full of what I love) as a reference to Bérénice by Jean Racine: "Mon cœur trop plein de votre image".

In act IV, Orion worries about the danger of his beloved, but Alphisa convinces him to rest his faith on Cupid, which "will dictate her answer" when she will be forced to tell Diana the truth. Convinced of her death, Alphisa will answer that she wants Diana to save Orion. Her fidelity is further recalled in act V, "I cannot be with whom I love; I should only seek death".

Orion

The authors reserve to the character of Orion various dramatic moments. As the titular character, he appears in every act. Nevertheless, the development of his character is mainly done in the first two acts.

The original placement at the beginning of act I of Orion's Sleep, which alarms him with a nightmare, serves to expose the drama and build the character of a reckless and gallant young lover, typical in the genre (e.g. Cadmos, Perseus, Athamas). In act II, Orion showcases his horror at the fatal oracle of Memnon. Convinced of his death, he expresses his bravery by begging that the gods to spare the life of his lover. This heroism is physically depicted through his onscene fight against the monster to save Alphisa. Act III shows Orion's resolution to betray his friend Pallantus in favour of love.

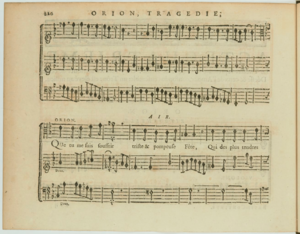

The monologue of Orion that begins act IV marks a shift of the libretto to a darker tone, while the hunter prepares the "sad and pompous Celebration" of the marriage of his "Rival". In act V, the horror that Orion feels when looking at the altar of sacrifice is overcome by his desire to "defy even Jupiter". This aspect also appears in the character of Perseus who, faced with difficult trials, confronts and triumphs over his obstacles with courage (although in the character of Perseus, courage manifests itself more by action than by speech). Thus, his ascent with Alphisa to the stars is reminiscent of that of Perseus and Andromeda's in Lully's opera.

Pallantus

The character of Pallantus, king of the Scythians, is the only character invented by the authors. The warning included in the book justifies the choice to make him king of the Scythians by the intention of putting him more out of reach for having dared to love Alphisa. In mythology, the Scythians live in a world dominated by frimats and are warriors who bear little mind to love in favor of glory. This soldier-like dimension has already been exploited in French opera (Orlando, Hercules or Tancred). Pallantus indeed represents the antithesis of this model, affirming throughout the tragedy his love for Alphisa.

Moreover, his character which was "too tender for a Scythian", coupled with his lack of or limited character dimension may relegate him to the secondary rank. Although he expressed his submission to the "victorious traits" of love in act I, it was not until the end of act III that he declared his love to Alphisa. His confession, however, was split between the nymph's dialogue with him and the ballet. During the party, the librettist entrusts the expression of love not to the king, but to a Scythian who can be considered as his double.

Until the end of act IV, the optimist king hoped to be "the happiest of Mortals". Pellegrin manages to make his character more dramatic by his sacrifice in act V, one of the touching moments of the libretto. While retaining his faithful love, Pallante finally succeeds in death to move Alphisa: "With my blood, I see your tears flowing; My fate is too happy. I die".

Literary posterity: Diana and Cupid

The conflict between Diana and Cupid will be used again by Simon-Joseph Pellegrin in his libretto for Hippolyte & Aricie by Jean-Philippe Rameau. Lucian of Samosata evokes this opposition in his Dialogues of the Gods (IInd century CE) during a discussion between Venus and Cupid. In this dialogue, Cupid evokes his fear towards Minerva, who has "Eyes like Lightning, and wears upon her Breast a Gorgon's Head, with Snakes for Tresses, that frights me out of my Wits"[52]. Ironically, Minerva in the prologue of Orion is in favor of Cupid. Diana in the dialogue is mentioned as being more concerned about her love for hunting, which takes place in her forests where Cupid struggles to follow her. However, Diana shows a violent and jealous love in Orion, justified by the librettists by quoting Noël le Comte. Indeed, the grammarian Diocles (also known as "Tyrannion the Younger") reports that Diana would have liked to marry Orion[53].

In Hippolyte & Aricie, Jupiter and Cupid appear again in the prologue, with Diana as the main character. This time it’s Diana’s place of worship which is invaded and challenged by Cupid. The goddess implores Jupiter to support her, but as in the prologue of Orion, he is favorable to Cupid and justifies himself with the edict of destiny. So, we find again Diana who grants her nymphs the freedom to love and the ballet dedicated to Cupid. The goddess swears to protect Hippolytus and Aricia, but refusing to "lower her pride", does not stay to observe the party. Throughout the opera, she plays the role of protector of love while remaining indifferent to that feeling.

Musical analysis

Unlike most of his contemporaries, like Toussaint Bertin de la Doué, Charles-Hubert Gervais or André Campra, Louis de La Coste rejects Italianism in his music and pays homage to the traditional French style that Jean-Baptiste Lully upholded and monopolized. However, he reappropriates this aesthetic while deploying he originality through a "very fine and characterized"[54] instrumental composition style throughout his career. The vocal composition in Orion differs from Lacoste's first four operas at the Académie de musique by being more virtuoso and lyrical (an approach that dates back to 1725 with Télégone).

Instrumental music

Use of traditional forms

Most of the time, Orion's instrumental composition respects the conventions of a tragédie lyrique: Lacoste shows his understanding of several genres of dance to support the highly developed ballet of the opera: Sarabande, Bourrée, Menuet, Passepieds, Gigue, Chaconne, Passacaille, March.

The tonalities are simple but varied: The ballet of the prologue is bathed in two colours, one in the tones of G, the other in C major. That of act I is in the luminous tone of C major, which contrasts with the C minor of the oracle following the ballet. The contrast between homonymous tones also appears in act III by the modulation from A major to a minor in the Chaconne. Respectively, the ballets of act II and that of act IV are generally in D major and in G minor, tones which according to Jean-Philippe Rameau are "of softness and tenderness". That of act V is entirely in F major.

The composer also uses ritornelli or preludes to introduce airs or characters. The French Overture of the opera also corresponds to the AABB-type structure of two movements: Slow (A) then fast (B).

Instrumental airs

A varied instrumentation

Lacoste employs an instrumentation that gives the opera a rural atmosphere to match the pastoral context of the libretto. Thus, one can spot multiple uses of the oboe, in particular in duet in a trio (Prélude pour Vénus - prologue; Marche pour Diane - act II). The bassoon is used in its high register as a solo timbre, distinguished from the basso continuo (Chaconne - act III).

The composer uses the traverso to cultivate ornate melodies to give character to the torments of Diana (Ritournelle - act V) or of Alphisa (Prélude - act III). It is also found as a solo timbre with basso continuo in a more joyful context ("Triopmhez puissante Déesse" - act V).

The natural trumpet is integrated into the prologue in the Prélude pour Minerve, but it is especially present in act I in the dances (Marche; Gigue) or in the choir "Reçois nos chants de victoire", to which the timpanis are also added. We also find in act II the hunting horn which plays a leitmotif which will be echoed frequently in the act.

Lacoste specifies for several pieces the use of the timbre of the violin and does not hesitate to use the mute (Deuxième Air - act IV). The violin is also used as the low voice in the trios, while two winds take the upper voices.

Harmonic language and melodic composition

The trio Sommeil d'Orion (act I) is an example of musical painting. To characterize the dream, the composer entrusts the soft and reduced orchestration (traverso, violin, bassoon) a rhythmic ostinato composed of half and eighth note values. To this figure, he adds glissandi and elevates the dynamics in order to characterize Diana's violence. Finally, to add anxiety to this figuralism, the composer spices up the orchestra with some chromaticisms (see audio).

On the harmonic level, Orion generally remains conservative and simple. Modulations commonly go towards the minor or major relative, the 5th, 4th or 2nd degree. However, Lacoste sometimes uses chromatism as well as prepared sevenths or ninths to give more expressiveness to the orchestra. These methods are more present in the accompaniment parts of vocal airs than in purely instrumental ones ("Que tu me fais souffrir"; "Fatal Auteur de mes alarmes" - act IV).

The pastoral ballet of this opera is also an opportunity to insert drone basses. From a functional point of view, we note that the bass in the air "Joignez les Tambours" (act I) and the Troisième Air (act III) alternates between the harmony of the tonic and that of the dominant.

Lacoste also plays with intervals with jumps of sixths and octaves, particularly in the Premier Air en Passacaille (act IV). He also uses the diminished third in the bass of Memnon's oracle "Le Destin dont je suis l'interprète" (act I) to signify death, a metaphor that Marc-Antoine Charpentier also attributes to this interval.

|

Prologue

|

Act I

|

|

Act II

|

Act III

|

|

Act IV

|

Acte V

|

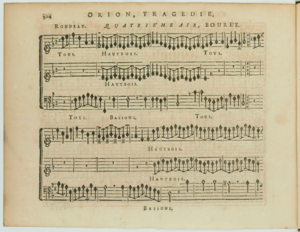

Vocal music

A developed demonstration of polyphonic composition

Lacoste's approach to counterpoint in the choirs of Orion is much more developed than the operas of Lully and his initial successors. He is not unique in this case: we can see that since the XVIIIth century, this style becomes crystallized with composers like André Campra or André Cardinal Destouches. In 1726, the arrival of François Francœur and François Rebel at the Opéra with Pyrame & Thisbé elevates it to a higher level. Despite the fact that all that remains to us is a reduced score, it is observable that the choir "Que du nom de Diane" (act IV), establishes a melismastic dialogue between the Dessus (Soprano) and the Basse-taille (Bass) voices. These long vocalizations are also alternated with homorythmic sections, instrumental parts and a trio with the highest voices : Dessus, Dessus 2 and Haute-contre (Tenor 1).

The fact that the libretto does not offer opportunities to have male trios (Basse-taille, Taille (Tenor 2), Haute-contre) is perhaps regrettable. The duets between Pallantus and Orion in act I, combined or not with the choir, may fill that gap. In regards to the duets, we can find one for two Nymphs, homorythmic and with light accompaniment on the violin: "Sans l'indifférence" (act II).

Exacerbated vocalists

At the start of the XVIIIth century, the French public began to clearly favor vocalizations, which became more and more virtuosic with a penchant for Italianism. The recruited singers receive more and more vocally demanding music. For example, in 1716, during a performance of Ajax by Bertin de la Doué, the Haute-contre Louis/Claude Murayre sang an aria composed for the castrato Nicolini in its original tonality[56].

It is therefore not surprising that Lacoste gives in to this trend, although he demands much less virtuosity and neglects the Italian influence. He especially gives the opportunity to the singer Petitpas, who is distinguished by her vocal qualities, both in operatic airs or cantatas. The air "Souveraine des Bois" (act II) allows her to show off her art of ornamentation, while "Digne Sœur du Père du jour" (act II) and "Dieu d'Hymen, après mille peines" (act V) demonstrates her coloratura abilities. The main actress Marie Antier and her double Julie Eeremans also find moments to showcase their vocal skills. The first exploits her low register and uses several glissandos in the air "J'ai triomphé d'un Monstre affreux" (act II). The second shows the lightness of her voice through the developed vocalizations of the air "Tout rit" and "Battez Tambours" from act I.

On the men's side, Denis-François Tribou, whose Haute-contre voice is generally more lyrical than his predecessors Murayre, Jacques Cochereau and Pierre Chopelet, receives some heroic vocalizations in his recitative "Je goûtais le repos..." (act I) and the air "Fille du Dieu puissant..." (act IV). Claude Chassé also finds occasions to show his vocal extension and flexibility with vocalizations and ornaments in the air "Ô Vous que le Destin..." (prologue) and "Unissez vos voix" (act III).

Lacoste also employs this more melodic and virtuoso compositional style in duets, like in the duet between Orion and Alphisa "Vole, Amour..." (act IV), remarkable for its attacks in the higher register and melodies in triplet.

The art of singing in support of the art of theater

The airs that Lacoste provides to the singers also make it possible to reinforce the dramatic qualities of the characters:

As the sole Tenor of the distribution, the role of Orion receives various big and small scale vocal pieces under multiple forms: For example, the recitativo secco "Mon bonheur passe mon attente" (act III) which, by the absence of complex ornaments and the changes of metrics, is an occasion for Tribou to focus more on declaiming the text, rather than singing it. As for the accompanied air "Amour si la Beauté..." (act I) which echoes the air "Bois épais..." from Amadis by the AABB form, it expresses the character's tenderness through trills or ports de voix, which can be varied in the reprises.

The role of Diana is also musically well taken care of. Her pain is expressed in the Rondeau "Fatal Auteur de mes alarmes" (act IV) by the intervals of sixths or fourths, violently attacked or by the metaphorical coulés and chutes de voix on the word "couler" (to flow). She also expresses her fury in her duet with Orion “Transports de haine & de rage” (act V), a syllabic and well-marked air, punctuated with rapid vocalizations.

The roles of Alphisa and Pallantus have fewer opportunities to express the dramatic quality of the libretto in their airs, more focused on the singing aspect. Nevertheless, through Alphisa's trills and ascending lines, Lacoste depicts her ardent love for Orion in her monologue "Qu'ai j'entendu..." (act III) while Pallantus balances between his tenderness for the nymph through ports de voix and his violence against the gods through attacks in his higher register in his final recitative in act V.

Vocal airs

Due to the reduction of the work, some vocal airs published in the score were not sung during the performances of the opera, something which the libretto testifies. The accompanied recitative "Je goûtais le repos..." and "L'effroi qu'un songe affreux m'inspire" (I, 1) and the air "Fille du Dieu puissant..." (IV, 5) of Orion, as well as the accompanied air "C'est trop à ma fierté..." (III, 5) of Diana are not listed as airs in the score, despite their distinct form.

|

Prologue

|

Act I

|

|

Act II

|

Act III

|

|

Act IV

|

Act V

|

*: airs whose words don't appear in the libretto

References

- Mercure de France, Mars 1728 (in French). Paris. 1728. p. 561.CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- Gregoir, Ėdouard Georges Jacques (31 December 1878). Des gloires de l'opéra et la musique à Paris, vol. 1 (in French). Paris: Schott frères. p. 64.

- "BaroquiadeS -- Ciel, mes constellations! - Fuoco e Cenere". www.baroquiades.com. 2 June 2019. Retrieved 2020-07-02.

- Parfaict, Claude; Parfaict, François (1767). Dictionnaire des théâtres de Paris, vol. 5 (in French). Paris: Rozet. p. 365.CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- Range: F4 - G5

- Range: G2 - D4

- Range: E♭4 - F5

- Younger sister of Marie Antier, creator of the role of Diana

- Range: F♯4 - F♯5

- Range: G4 - G5

- Range: B♭ 3 - A5 Although it is written with the first C Clef and has various high notes, this role should preferably be referred to as a Bas-dessus (Mezzo-soprano), in consideration of its creator and its extension in the lower register.

- Range: F3 - B♭4

- Range: G2 - F4

- Range: D4 - G5

- Range: D3 - D4

- Range: F♯4 - A5

- Range: C4 - G5

- Famous virtuoso singer, Petitpas made her debut at the Opera in Orion after having doubled Marie Pélissier in Pyrame & Thisbé

- Range: E2 - E4

- Range: D4 - G5

- Wife of Jean II Dun, her unmarried name was "Catin"

- Range: F♯4 - G5

- This role was mute during the performances of the opera.

- Range: C3 - D4

- The creator of this role was not named in the libretto

- Range: G4 - G5

- This role only appears in the score of the opera, in the final ballet of act V. From the review of the Mercure de France, which resumed the end only with "The people sung Diana's new victory", we can conclude that the ballet was never performed.

- Father of Jean II Dun

- He is named "Rebourg" in the libretto

- First younger sister of Marie-Anne de Camargo

- Fourth of the Dumoulin brothers

- Uterine brother of François, David et Pierre from the Dumoulin family

- Second of the Dumoulin brothers

- The ballet of this act was reduced to one chorus "Chantons la nouvelle victoire", although the music has been printed

- Petite bibliothèque des théâtres, vol. 57, Chef-d'œuvre de Lafont (in French). Paris: Bélin, Brunet. 1788. p. 18.CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- de La Font, Joseph; Pellegrin, Simon-Joseph (1728). Orion, tragédie, représentée pour la première fois, par l'Académie royale de Musique, le dix-septième jour du mois de Février 1728. University of Western Ontario. Paris: Jean-Baptiste-Christophe Ballard. pp. iii.CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- Parfaict, François; Parfaict, Claude (1756). Dictionnaire des théâtres de Paris, vol. 4 (in French). Paris: Lambert. p. 35.CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- Joseph, de La Font; Pellegrin, Simon-Joseph (1728). Orion, tragédie, représentée pour la première fois, par l'Académie royale de Musique, le dix-septième jour du mois de Février 1728. Paris: Christophe Ballard. p. 56.

- Mercure de France, Mars 1728. Paris. 1728. p. 680.

- Petite bibliothèque des théâtres, vol. 57, Chef-d'œuvre de Lafont (in French). Paris: Bélin, Brunet. 1788. p. 64.CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- Favre, Georges (1971). Revue de Musicologie, T. 57, No. 2 (1971) : Un prince mélomane au XVIIIe siècle. La vie musicale a la Cour d'Antoine Ier, prince de Monaco (1661-1731). Société Française de Musicologie. p. 138.

- Mercure de France, Mars 1728 (in French). Paris. 1728. p. 574.

- Mercure de France, Mars 1728 (in French). Paris. 1728. p. 576.

- Mercure de France, Mars 1728 (in French). Paris. 1728. p. 571.

- Mercure de France, Mars 1728 (in French). Paris. 1728. pp. 578–579.

- Mercure de France, Mars 1728 (in French). Paris. 1728. pp. 568–569.

- Mercure de France, Mars 1728 (in French). Paris. 1728. p. 574.

- Mercure de France, Mars 1728 (in French). Paris. 1728. p. 579.

- Mercure de France, Mars 1728 (in French). Paris. 1728. p. 579.

- Girdlestone, Cuthbert (1972). La tragédie en musique (1673-1750) considérée comme genre littéraire (in French). Geneva-Paris: Librairie Droz. p. 258. ISBN 978-2-600-03520-0.

- Dictionnaire de l’Opéra de Paris sous l’Ancien Régime (1669-1791) Tome III – H-O. Paris: Classiques Garnier. 2019. p. 948. ISBN 978-2-406-09673-3.

- Samosata, Lucian of (1772). Lucian's Dialogues, Selected by Dugard, and Leeds. Translated by Dryden, and Several Eminent Hands. Dublin: W. Smith, H. Bradley, and T. Ewing. p. 149.

- Bell, John (1790). Bell's New Pantheon: Or, Historical Dictionary of the Gods, Demi-gods, Heroes, and Fabulous Personages of Antiquity, Vol. II. London: J. Bell. p. 143.

- Dictionnaire de l’Opéra de Paris sous l’Ancien Régime (1669-1791) Tome I – A-C. Paris: Classiques Garnier. 2019. p. 564. ISBN 978-2-406-09061-8.

- Ranum, Patricia M. (2001). The Harmonic Orator: The Phrasing and Rhetoric of the Melody in French Baroque Airs. New York: Pendragon Press. p. 445. ISBN 978-1-57647-022-0.

- Colas, Damien; Profio, Alessandro Di (2009). D'une scène à l'autre, l'opéra italien en Europe: Les pérégrinations d'un genre (in French). Wavre: Editions Mardaga. p. 263. ISBN 978-2-87009-992-6.

External links

- Orion at operabaroque.fr

- Reduced score at gallica.bnf.fr

- Reduced score at archive.org

- Libretto at archive.org

- Libretto at philidor.cmbv.fr

Sources

- (in French) Libretto at "Livrets baroques"

- (in French) Félix Clément and Pierre Larousse Dictionnaire des Opéras, Paris, 1881, page 501.