Ordnance Survey of Jerusalem

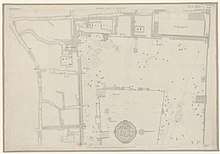

The Ordnance Survey of Jerusalem of 1864–65 was the first scientific mapping of Jerusalem, and the first Ordnance Survey to take place outside the United Kingdom.[1] It was undertaken by Charles William Wilson, a 28-year-old officer in the Royal Engineers corps of the British Army, under the authority of Sir Henry James, as Superintendent of the Ordnance Survey, and with the sanction of George Robinson, 1st Marquess of Ripon as Secretary of State for War. The team of six Royal Engineers began their work on 3 October 1864. The work was completed on 16 June 1865, and the report was published on 29 March 1866.[2]

| Ordnance Survey of Jerusalem | |

|---|---|

Front page of the Ordnance Survey of Jerusalem, illustrated with the Chain Gate fountain. See full pdf of the Ordnance Survey here | |

| Created | 1864–65 |

| Location | The National Archives (United Kingdom) |

| Author(s) | Charles William Wilson |

During the resulting search, he produced "the first perfectly accurate map [of Jerusalem], even in the eyes of modern cartography",[3] and identified the eponymous Wilson's Arch but was unable to find a new source of water.[4]

Over a century after the survey, Dan Bahat described it as "a watershed in the exploration of Jerusalem and its past",[5] and The Jerusalem Post commented that Wilson's efforts "served as the basis for all future Jerusalem research".[6]

The survey provided the foundation and impetus for the creation of the Palestine Exploration Fund.[7] The first meeting of the Fund took place on 22 June 1865, less than a week after the completion of the Ordnance Survey, and Charles Wilson was appointed by the Fund as the Chief Director of their proposed exploration of the rest of Palestine.[5][8] In July 1866 Dean Stanley described the Ordnance Survey as a "sort of pre-historic stage of our Palestine Exploration Fund".[9]

It was the most influential and reliable map of Jerusalem until the British Mandate's Survey of Palestine, which published a 1:2,500 map of the Old City of Jerusalem in 1936.[10]

History

The survey was catalyzed by an 1864 petition from Arthur Penrhyn Stanley (the Dean of Westminster), representing a committee which included the Bishop of London Archibald Campbell Tait to George Robinson, 1st Marquess of Ripon (the Secretary of State for War). Dean Stanley had accompanied the Prince of Wales (later Edward VII) on his 1862 trip to Jerusalem; his request was for an improvement to the city's water supply.[11]

The cost of providing the Royal Engineers surveyors (Wilson and his team) was covered by the British Government's War Office.[12] The introduction to the survey stated that the ₤500 cost of the survey was funded by the wealthy Angela Burdett-Coutts, 1st Baroness Burdett-Coutts, whose primary motivation was to find better drinking water for those living in the city. However, the issue of “water relief” to the city was subsequently sidelined; in the words of Moscrop “the issue just vanishes,” and no improvements were made to the water supply until the end of the century.[7]

As Austen Henry Layard made clear at the first public meeting of the PEF on 22 June 1865, the Ordnance Survey had been conducted “under the auspices of the War Department and with the sanction of the Government”[13]

Legacy

One of the survey's most significant aspects was that it was the first work to investigate the underground features of the Temple Mount (referred to in the survey as the Haram As-Sharif), such as its cisterns, channels and aqueducts.[14]

Archaeologist Shimon Gibson summed up the legacy of the Ordnance Survey of Jerusalem as follows (underline added): [15]

What is quite clear is that a major change in the character of the exploration of ancient Jerusalem occurred in the 19th century, with a fascination for the past of the city, fanciful or otherwise, being replaced by that of a scientific concern for the tangible antiquities of the city. The Ordnance Survey conducted by Wilson in 1864 and 1865 marks this turning point. The ancient past of Jerusalem was no longer a matter for armchair scholarly discourse, turning upon the credibility and background of a given scholar, but had now become a matter for clear-cut scientific rigor, which could only be based on facts obtained in empirical fashion, whether through the taking of exact measurements, photography, or excavations in the ground.

The names of streets, buildings and points of interest were collected by Carl Sandreczki of the Church Mission Society and two assistants.[16] Sandreczki's list, which included the names written in Arabic, is an invaluable resource as it contains many items that have otherwise been lost.[17]

Bibliography

Primary sources

- Wilson, Charles; James, Henry (1865). Ordnance survey of Jerusalem / made with the sanction of the Right Hon. Earl de Grey and Ripon, Secretary of State for War, by Captain Charles W. Wilson, R. E., under the direction of Colonel Sir Henry James ... director of the Ordnance Survey. Pub. by authority of the Lords Commissioners of Her Majesty's Treasury. H. M. Stationery Office.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wilson, Sir Charles William; Warren, Sir Charles (1871). The Recovery of Jerusalem: A Narrative of Exploration and Discovery in the City and the Holy Land. R. Bentley.

Secondary sources

- Moscrop, John James (1 January 2000). Measuring Jerusalem: The Palestine Exploration Fund and British Interests in the Holy Land. A&C Black. ISBN 978-0-7185-0220-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- H. E. M. Newman (1958). The work of the Ordnance Survey outside Great Britain and Ireland. Ordnance Survey.

- Chapman, Rupert, "British Archaeology and the Holy Land in the 19th Century: sources and a framework for study'", Britain and the Holy Land 1800–1914

- Kamel, Lorenzo (2014). "The Impact of "Biblical Orientalism" in Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth-Century Palestine". New Middle Eastern Studies. 4.

- “Institutionalization.” Finding Jerusalem: Archaeology between Science and Ideology, by Katharina Galor, University of California Press, Oakland, California, 2017, pp. 28–42. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/j.ctt1pq349g.9.

- Gibson, Shimon (2011). "British Archaeological Work in Jerusalem between 1865–1967: An Assessment". In Katharina Galor and Gideon Avni (ed.). Unearthing Jerusalem: 150 Years of Archaeological Research in the Holy City. Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-1-57506-223-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schelhaas, Bruno; Faehndrich, Jutta; Goren, Haim (28 February 2017). Mapping the Holy Land: The Foundation of a Scientific Cartography of Palestine. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85772-785-5.

- Seymour, W. A. (1980). "The Surveys of Jerusalem and Sinai". A History of the Ordnance Survey. Dawson. ISBN 978-0-7129-0979-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bahat, Dan (1980). "Introduction: The Ordnance Survey and its contribution to the study of Jerusalem". Ordnance Survey of Jerusalem (Facsilime ed.). Ariel Publishing House.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Galor, Katharina (24 March 2017). Finding Jerusalem: Archaeology Between Science and Ideology. Univ of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-29525-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Levy-Rubin, Milka; Rubin, Rehav (1996). "The Image of the Holy City: Maps and Mapping of Jerusalem". In Nitza Rosovsky (ed.). City of the Great King: Jerusalem from David to the Present. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-36708-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Foliard, Daniel (13 April 2017). Dislocating the Orient: British Maps and the Making of the Middle East, 1854-1921. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-45147-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

References

- Foliard 2017, p. 42a: “Of the many institutions involved in surveying and mapping the Orient, the Ordnance Survey might seem the most unlikely. It had developed as the main mapping organization for the British Isles and was placed under the authority of the WO in 1855. Its surveys had been strictly limited to the United Kingdom until that point. Despite this, the institution participated in one of the most systematic mapping projects of the mid- Victorian age in the East. Henry James, its director between 1854 and 1875, was keen to enlarge the scope of its surveys and, in a break with its normal practice, sponsored a survey of Palestine. The first expedition explored Jerusalem in 1864–65.”

- Ordnance Survey, pp. 1, 2, 16

- Levy-Rubin & Rubin 1996, p. 378.

- Gibson 2011, p. 26.

- Bahat 1980, p. 1.

- Glatt, Benjamin (25 October 2016). "Surveying Jerusalem". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- Moscrop 2000, p. 57.

- Ordnance Survey, p.2-3

- Gibson 2011, p. 29: Gibson cites: “Report, July 23rd 1866,” PEF Proceedings and Notes, 1865–69: 19".

- PALESTINE: ANNUAL REPORT, 1936, OF THE DEPARTMENT OF LANDS AND SURVEYS, Empire Survey Review, 4:28, 362-380, DOI: 10.1179/sre.1938.4.28.362, pages 368, 368: "In 1936 a complete map of the Old City of Jerusalem was published on the scale 1/2,500. The only previous map of the Old City was that made in 1865 by Sir Charles Wilson, previously mentioned. This map is apparently often called by writers the Ordnance Survey of Jerusalem! Anyhow, it proved itself worthy of the title, for Lieut-Col F. J. Salmon states that it was sufficiently accurate to be used as the framing of the new map. The old map showed no more than the streets and principal edifices; the new shows all the structures… Large-scale maps were also undertaken, including a 1/2,500 plan of the Old City of Jerusalem, previously mentioned. Provisional plans of Jerusalem and environs, on a scale of 1/5,000, were drawn and printed, though the survey was held up by the disturbances to a degree which is obviously not overestimated. These will subsequently be reduced to 1/10,000-a general map in demand for the city."

- Seymour 1980, p. 154.

- Foliard 2017, p. 42.

- Gibson 2011, p. 26-27: Gibson quotes: “Public Meeting, June 22nd 1865,” PEF Proceedings and Notes, 1865–69: 7"

- Galor 2017, p. 31.

- Gibson 2011, p. 52.

- Wilson & James 1865, p. 18.

- Bahat 1980.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ordnance Survey of Jerusalem. |