Orchestra hit

An orchestra hit, also known as an orchestral hit, orchestra stab, or orchestral stab, is a synthesized sound created through the layering of the sounds of a number of different orchestral instruments playing a single staccato note or chord.[1] The orchestra hit sound was propagated by the use of early samplers, particularly the Fairlight CMI where it was known as the ORCH5 sample[2]. The sound is used in pop, hip hop, jazz fusion, techno, and video game genres to accentuate passages of music.[3]

Synthesized orchestra hit from Roland's VSC3 | |

| Other instrument | |

|---|---|

| Classification | Digital sample |

| Developed | Early 1980s |

| Musicians | |

| David Vorhaus, Trevor Horn, Duran Duran | |

The orchestra hit has been identified as a "hip hop cliché".[4] In 1990, Musician magazine stated that Fairlight's ORCH5 sample was "the orchestral hit that was heard on every rap and techno-pop record of the early 1980s".[5] The orchestra hit has been described as popular music's equivalent to the Wilhelm scream, a sound effect widely used in film.[6]

History

Precursors to the popular samples can be found in contemporary classical music, for example in Igor Stravinsky's ballet The Firebird (1919).

Use of short samples (such as the orchestra hit) became popular in the early 1980s with the advent of digital samplers.[7] These devices allowed sounds to be replayed at specific times and at regular intervals by sequencing, which was extremely difficult through previous methods of tape splicing.[7] Samplers also began to allow sections of audio to be edited and played by a keyboard controller.[7]

The orchestra hit was popularised in Afrika Bambaataa's "Planet Rock" (1982)[8] and used soon after in Kate Bush's "The Dreaming".[9] Other examples of use in popular music include En Vogue's "Hold On" (1990)[10] and Duran Duran's "A View to a Kill" (1985).[11] Yes's "Owner of a Lonely Heart" (1983) used an orchestra hit which was sampled from Funk, Inc.'s "Kool is Back".[12] By the mid 1980s, the orchestra hit had become commonplace in hip hop music,[13] and its ubiquitous use became a cliché.[14] Use in other genres extends to jazz funk, where it was used on the title track of Miles Davis's 1986 album Tutu.[15] By the mid 1990s the sound had begun to be used in caribbean music.[1][16]

Anne Dudley and Trevor Horn used an orchestra hit with the Art of Noise as a sound effect rather than a melodic instrument.[9] The sample was used in "Close (to the Edit)", where it was sequenced alongside sound effects of chainsaws, breaking glass and motorcycles.[17] Similarly, the brass orchestra hits in "Owner of a Lonely Heart" are used as a rhythmic device, rather than an effect to evoke a specific environment (in a similar way to samples in Yes's earlier recordings).[7] The stabs in the song may also be substitutes for other instruments in the rhythm section, possibly drum fills, and the use of orchestra hits and other samples is particularly noticeable between the first chorus and the start of the guitar solo.[7] High-pitched versions of the orchestra hit were used in many late 80s and 90s songs in Eastern Europe, for example one notable use there was in the song "S'agapao pou na parei" (Σ'αγαπάω που να πάρει) by Greek singer Thanos Kalliris in 1997.

Orchestra hits are sometimes used in film music to represent loud noises such as closing doors.[18]

Technical

Orchestra hit is defined in the General Midi sound set.[19] It is assigned voice 55, in the ensemble sub group.

The Fairlight CMI synthesizer included a sampled orchestra hit voice, which was later included in many sample libraries.[12] The voice was given the name ORCH5, and was possibly the first famous orchestra hit sample.[20] The sound was a low-resolution, eight-bit digital sample from a recording of Stravinsky's Firebird Suite[8] – specifically, the chord that opens the "Infernal Dance" section, pitched down a minor sixth and at a reduced speed.[21] It was sampled by David Vorhaus.[21] Music magazine The Wire suggests that the prototype sample is owned by Vivian Kubrick.[22]

Early orchestra hits were short in duration (often less than a second) both due to the nature of the sound (a staccato note) and the restrictions on bit rates and depths. A compromise for longer durations would be lower bitrates, which would leave the sample with little timbre.[7]

Fairlight produced a number of orchestra hit samples, including a chord version (TRIAD), a percussion version (ORCHFZ1) and a looped version (ORCH2).[21] Samples ORCH4, ORCH5 and ORCH6 were located on the CMI's disk 8, within the STRINGS1 library.[23]

Samples

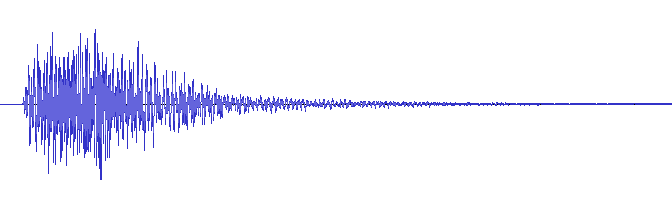

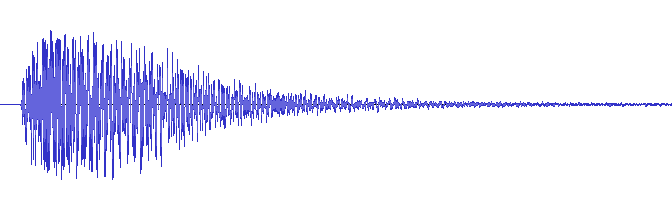

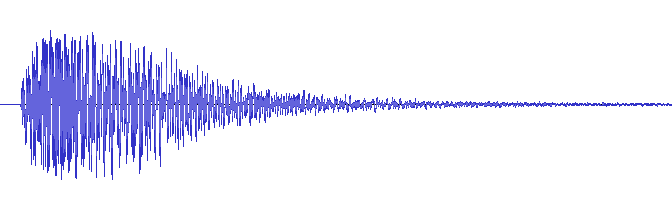

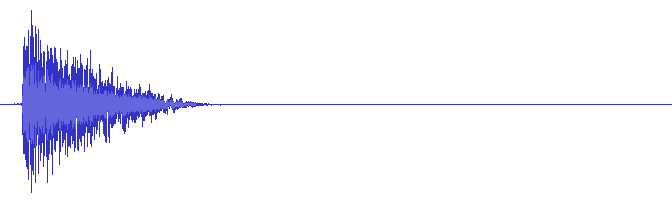

The following samples are examples of orchestra hit voices on different sound modules. Each note is played at C4 (see scientific pitch notation).

| Synthesizer | Sample | Waveform |

|---|---|---|

| Roland Virtual Sound Canvas 3 |  | |

| Yamaha CS1X |  | |

| Yamaha MU50 |  | |

| Yamaha PSS31 |  |

See also

Footnotes

- Best (2004, p. 72)

- "The sound that connects Stravinsky to Bruno Mars". youtube. Vice Media. 15 May 2018. Retrieved 23 February 2020.

- Fink (2005, p. 14)

- Fink (2005, p. 6)

- Musician (1990)

- Kopstein (2011)

- Warner (2003, p. 69)

- Fink (2005, p. 1)

- Fink (2005, p. 5)

- GPI Publications (1994, p. 11)

- Holmes (1997)

- Di Nicolantonio (2004)

- Fink (2005, p. 15)

- Warner (2003, p. 105)

- Sabin (2002, p. 206)

- Best (2004, p. 73)

- Weisbard (2007, p. 238)

- Machin (2010, p. 157)

- Rothstein (1995, p. 56)

- Fink (2005, p. 2)

- Fink (2005, p. 3)

- The Wire (2007, p. 64)

- Synthiman (2007)

Sources

- Best, Curwen (2004), Culture at the Cutting Edge: Tracking Caribbean Popular Music, Kingston, Jamaica: University of the West Indies Press, ISBN 976-640-124-1

- Di Nicolantonio, Paolo (2004), Famous Sounds, SynthMania, retrieved 22 February 2011

- Fink, Robert (2005), "The Story of ORCH5, or, the Classical Ghost in the Hip-Hop Machine", Popular Music, 24 (3): 339–356, doi:10.1017/S0261143005000553, JSTOR 3877522

- GPI Publications (1994), Keyboard, 20, retrieved 22 February 2011

- Holmes, Greg (1997), Fairlight CMI Examples, GH Services, retrieved 22 February 2011

- Kopstein, Joshua (2011), The Fairlight CMI's 'ORCH5' Is The Sample You Haven't Not Heard, MotherBoard, retrieved 22 February 2011

- Machin, David (2010), Analysing Popular Music: Image, Sound and Text, Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, ISBN 978-1-84860-023-2

- Rothstein, Joseph (1995), MIDI: A Comprehensive Introduction, Middleton, WI: A-R Editions, ISBN 0-89579-309-1

- Sabin, Ira (2002), Jazz Times, 32, retrieved 22 February 2011

- Musician (1990), Issues 135-140, Boulder, CO: Amordian Press

- Synthiman (2007), Fairlight CMI IIx, retrieved 22 February 2011

- The Wire (2007), Issues 275-280, London: The Wire Magazine Ltd

- Warner, Timothy (2003), Pop Music: Technology and Creativity – Trevor Horn and the Digital Revolution, Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate Publishing, ISBN 0-7546-3132-X

- Weisbard, Eric (2007), Listen Again: A Momentary History of Pop Music, Durham, NC: Duke University Press, ISBN 978-0-8223-4022-5