Operation Dixie

Operation Dixie was the name of the post-World War II campaign by the Congress of Industrial Organizations to unionize industry in the Southern United States, particularly the textile industry. Launched in the spring of 1946, the campaign ran in 12 Southern states and was undertaken as part of a dual effort to consolidate wage gains won by the trade union movement in the Northern United States by raising wage levels in the South while simultaneously transforming the conservative politics of the region, thereby allowing the trade union agenda to win on a national scale.

Operation Dixie failed largely due to Jim Crow laws and the deep-seated racial strife in the South which made it difficult for black workers and poor whites to engage cooperatively for successful union organization. The passage of the Taft-Hartley Act additionally undercut the campaign, making it easier for employers to obstruct union organizing drives by inhibiting the right to strike and allowing prohibition of closed shops. The Cold War Red Scare also hurt the union movement throughout the United States by increasing hostility to the left in general and unions in particular.

The CIO's defeat in Operation Dixie was a contributing factor in the decision of the traditionally more radical trade union federation to merge with the conservative American Federation of Labor and form the AFL–CIO in 1955 — a move that signified a long-term trend away from radical social unionism towards the more conservative business unionism strategy long favored by the AFL. In the long-term, the failure of Operation Dixie to end the South's status as a low-wage, non-union haven impeded the ability of the union movement to maintain its strength in North and was a contributing factor in the decline of the American union movement in the second half of the 20th century as unions were unable to prevent businesses from holding back wage increases by either moving to the South or threatening to do so.

History

Background

The American trade union movement was largely a Northern phenomenon at the time of its inception, with the first continuous organization for the advancement of wages emerging among the shoemakers of Philadelphia in 1792.[1] This was followed by the printers of New York City in 1794, and various groups of shoemakers and printers in the Northern cities of Baltimore, Pittsburgh, Boston, Albany, and Washington, D.C. in the years up to 1809.[1] It was not until 1810 that the first Southern American trade union emerged, that being an organization of the printers of New Orleans.[2]

As the North industrialized at a more rapid rate than the largely agrarian South during the 19th Century, unions organizing industrial workers were gradually established throughout New England and the Northeast as well as the emerging industrial mecca of Chicago. Development of the slavery-based Southern plantation economy not only lagged behind the North in its pace of industrialization and unionization but in some respects differed fundamentally from the Northern path of economic development.

American trade union movement showed tremendous growth during the more than 12 years of the administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, growing from fewer than 3 million members in 1933 to more than 14 million in 1945.[3] Even during World War II there had been significant gains in the penetration of trade unions across the South, including in particular union growth such industrial centers as Memphis, Birmingham, Atlanta, Baton Rouge, Galveston, and Tampa.[3] Southern unionization was not limited to any single industry, with union growth being noted in a broad range of productive activities, including coal and metal mining, tobacco production, paper manufacturing, oil refining, and to some extent textile production.[3]

The stage seemed set for further union growth across the region as the wars in Europe and the Pacific drew to a close and industry began to gear up to slate long pent-up consumer demand.

Unionization of the South was seen as critical to the American labor movement. While fully 35% of the American non-agricultural labor force were members of trade unions in 1945, lack of a union presence in the South prevented pro-union majorities from gaining power in Congress, allowing pro-business Republicans and conservative Southern Democrats to work together to stymie organized labor's political agenda.[4] Moreover, the lack of unionization in the South made possible the flight of capital to Southern locations with lower labor costs, thereby undercutting union bargaining power nationwide. Mass organization of low wage Southern workers by the CIO would thus achieve the dual purpose of protecting contract gains elsewhere and making the regional and national political climate into one favorable to labor, union leaders believed.[5]

Launch of Operation Dixie

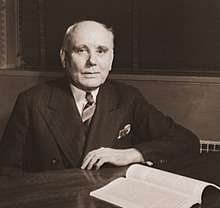

The first step by the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) towards Operation Dixie came in September 1945 when CIO President Philip Murray appointed a 7-member committee given the task of assessing organizing opportunities for the union in the postwar period.[6] Citing the conservative political climate and low wage economic conditions of the region, the committee returned with a report declaring that "the best place for the CIO to undertake organizing...would be in the South."[7] Internal discussions proceeded throughout the fall and winter of 1945–46, with the governing Executive Board of the CIO signing on to a plan massive campaign to unionize the whole of manufacturing industry in the Southern United States in March 1946.[6]

At the time of the launch of Operation Dixie, CIO membership in the Southern United States stood at about 225,000 — a figure excluding the 100,000 Southern members of the United Mine Workers of America, a union which had disaffiliated from the CIO federation in 1942.[8] About 42,000 of these were represented by the CIO-affiliated Textile Workers Union of America.[8] Other important CIO unions in the region included the United Cannery, Agricultural, Packing, and Allied Workers of America (UCAPAWA), the United Steelworkers of America (USWA), as well as the Oil Workers' Union, Shipbuilding Workers, and Rubber Workers' Union.[9]

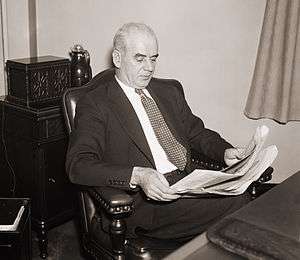

A permanent Southern Organizing Committee (SOC) was appointed, a group which included top officials of the United Auto Workers (UAW), the United Electrical Workers (UE), the Textile Workers' Union of America, and the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America, among other member unions.[6] Veteran Steelworkers' Union organizer Van Bittner was named as director of the SOC, with 39-year-old Textile Workers' Union Vice President George Baldanzi tapped as Bittner's right-hand man.[6] A total of $1 million was to be raised for the effort by the CIO, with its member unions assessed percentage shares of the cost based on membership size.[6] A total of 200 organizers were to be put into the field as part of Operation Dixie, which was seen by union officials as a return to the methods successfully employed to organize the steel industry in 1936 and 1937.[6]

This campaign was touted by CIO President Murray as "the most important drive of its kind ever undertaken in the history of this country" and was the spur to a parallel organizing effort in the South by the rival American Federation of Labor, beginning with an AFL Southern Labor Conference that same May.[10]

Organizing tactics

The CIO's strategy was to target specific geographic locations within the Southern region and to send in teams of organizers into each of these locations to "proceed to organize everything in sight.[6] Union initiation fees of $1.00 and dues of $1.50 per month were to be collected from workers being organized, with the funds collected returned to the regional organizing campaign.[11] Military veterans were to be exempt from these dues and fees.[11] Southern Organizing Committee headquarters were to be based in Atlanta and the committee would work closely with the various CIO unions in resolving jurisdictional disputes as they arose.[11]

Seed money from the member unions was substantial, with the Steelworkers and UCWA contributing $200,000 each, the Textile Workers $125,000, and the Auto Workers, the UE, and CIO headquarters each chipping in $100,000 to the Operation Dixie campaign.[11]

Footnotes

- David J. Saposs, "Early Trade Unions," in John R. Commons et al., History of Labour in the United States: Volume 1. New York: Macmillan, 1918; pp. 108–109.

- Saposs, "Early Trade Unions," pg. 109.

- Goldfield, "The Failure of Operation Dixie," pg. 167.

- Goldfield, "The Failure of Operation Dixie," pp. 167–168.

- Robert H. Zieger, The CIO, 1935–1955. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1995; pg. 227.

- Zieger, The CIO, 1935–1955, pg. 231.

- Quoted in Zieger, The CIO, 1935–1955, pg. 231.

- Zieger, The CIO, 1935–1955, pg. 229.

- Ziger, The CIO, 1935–1955, pp. 229–230.

- Michael Goldfield, "The Failure of Operation Dixie: A Critical Turning Point in American Political Development?" in Gary M. Fink and Earl E. Reed (eds.), Race, Class, and Community in Southern Labor History. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press, 1994; pg. 166.

- Zieger, The CIO, 1935–1955, pg. 232.

Further reading

- Griffith, Barbara S. The Crisis of American Labor: Operation Dixie and the Defeat of the CIO. (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1988)

- Haberland, Michelle. Striking Beauties: Women Apparel Workers in the U.S. South, 1930–2000 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2015) xii, 228 pp.