Ongud

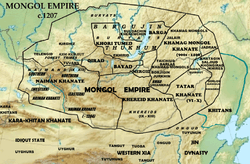

The Ongud (also spelled Ongut or Öngüt; Mongolian: Онгуд, Онход; Chinese: 汪古, Wanggu) were a tribe active in Mongolia around the time of Genghis Khan (1162–1227).[1] Many Ongud were members of the Church of the East.[2] They lived in an area lining the Great Wall in the northern part of the Ordos Plateau and territories to the northeast of it.[1] They appear to have had two capitals, a northern one at the ruin known as Olon Süme and another a bit to the south at a place called Koshang or Dongsheng.[3] They acted as wardens of the marches for the Jin dynasty (1115–1234) to the north of Shanxi.[4]

History and Origin

The ancestors of the Ongud were the Yueban who later intermixed with Turkic peoples, forming the Shatuo of the Western Turkic Khaganate.[5] In the seventh century they moved to eastern Xinjiang under the protection of the Tang China. By the ninth century, the Shatuo were scattered over North China and modern Inner Mongolia. A Shatuo warlord, Li, mobilized 10,000 Shatuo cavalrymen and served Tang China as an ally. In 923, his son defeated the rebellious dynasty and became emperor of the Later Tang.

After the overthrow of the Li family, Shatuo commanders established the Later Jin, the Later Han and the Northern Han.

In the 13th century, a part of Shatuo probably included in the Mongol Empire as an Ongud tribe, another part as White Tatars.[6][7]

The Ongud chief Ala Kush Tegin revealed the Naimans plan to attack Genghis Khan in 1205 and allied with the Mongols. When Genghis Khan invaded the Jin Dynasty in 1211, Ala Kush Tegin supported him. Genghis bestowed his daughter Alaga Bekhi on his son. However, the political opponents killed Ala Kush Tegin. Genghis put down the rebellion and took the family under his protection. Genghis Khan's daughter Alaga ruled the Ongud as regent for several underage princes until the reign of Güyük Khan (1246–48).

Many famous post-Genghis Mongols are of Ongud descent, including the well-known traveler, diplomat, and monk of the Church of the East, Rabban Bar Sauma (1220–1294). The Ongud proved good allies to Kublai.[8] For example, the Ongud ruler Korgiz (George) married Kublai's two granddaughters and fought against Kaidu, whose protégé Duwa captured and killed him later in 1298. A number of Öngüd were said to have been converted to Catholicism by John of Montecorvino (1246–1328).

After 1221 many Onguds were resettled in Khwarezm, where they served as governors for the Golden Horde. They formed part of the Argyns and the Mughal tribe. The Onguds in Mongolia became an otog of the Tumed in the 15th century. The Onguds gradually vanish from records and likely assimilated into other Turkic and Mongol tribes beginning in the post-Yuan period. The Mongols of Inner Mongolia, Mongolia and western China eventually converted to Tibetan Buddhism from the 16th century onwards.[9]

Art and architecture

The University of Hong Kong possesses a collection of around a thousand 13th- and 14th-century bronze Nestorian crosses from the Ongud region collected during the 1920s by F. A. Nixon, a British postal official working in northern China. Although their designs vary, Maltese crosses with a square central panel displaying a swastika, the Buddhist good luck symbol, predominate.[10]

The Ongud Monument Ensemble was constructed by the Turkic tribes during the 6th-8th centuries for their noblemen. This consists of over 30 man-like figures, a lion and a sheep, and about 550 standing stones in alignments reminiscent of Carnac or Avebury. There is also a large tomb made of 4 sculptured slabs. Each slab has the front face decorated with a trellis-pattern like the walls of a yurt, and a simple frieze on top.

See also

- List of medieval Mongolian tribes and clans

- History of Mongolia

- Christianity among the Mongols

Notes

- Roux, p.40

- Phillips, p. 123

- Halbertsma, Tjalling H. F. (2008). Early Christian Remains of Inner Mongolia: Discovery, Reconstruction and Appropriation. Brill. pp. 150–157. ISBN 978-90-04-16708-7.

- Saunders, John Joseph (2001). The History of the Mongol Conquests. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 52. ISBN 0-8122-1766-7.

- C. P. Atwood, Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire, p.424

- Wang Kuo-wei, "Wang Kuo-wei researches", Taipei, 1968: 4985

- Ozkan Izgi, "The ancient cultures of Central Asia and the relations with the Chinese civilization"//The Turks, Ankara, 2002, p. 99

- John Man Kublai khan, p.319

- Tang, Li (2011). East Syriac Christianity in Mongol-Yuan China. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 148. ISBN 978-3-447-06580-1.

- F. S. Drake, 'Nestorian Crosses and Nestorian Christians in China under the Mongols', Journal of the Hong Kong Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 1962

References

- Phillips, J. R. S. (1998). The Medieval Expansion of Europe (second ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-820740-9.

- Roux, Jean-Paul, Histoire de l'Empire Mongol, Fayard, ISBN 2-213-03164-9