Taxiles

Taxiles (in Greek Tαξίλης or Ταξίλας; lived 4th century BC) was the Greek chroniclers' name for the prince (later king) who reigned over the tract between the Indus and the Jhelum (Hydaspes) Rivers in the Punjab region of the Indian subcontinent at the time of Alexander the Great's expedition. His real name was Ambhi[1] (Greek: Omphis), and the Greeks appear to have called him Taxiles or Taxilas, after the name of his capital city of Taxila, near the modern city of Attock, Pakistan.[2][3]

Life

Ambhi ascended to the throne of Takshasila after his father Ambhiraj.[4] He sent an embassy to Alexander along with presents consisting of 200 Talents of silver, 3,000 fat oxen, 10,000 sheep or more, 30 elephants and a force of 700 horsemen and offered for surrender.[4] He, contrary to the diplomatic practices of his father Aambhiraj, appears to have been on hostile terms with his neighbour, Porus, who held the territories east of the Hydaspes.[5][6] It was probably with a view to strengthening himself against this foe that he sent an embassy to Alexander, while the latter was still in Sogdiana, with offers of assistance and support, perhaps in return for money.[5] Alexander was unnerved by the sight of Aambhi's forces on his first descent into India in 327 BC and ordered his own forces to form up.[7] Aambhi hastened to relieve Alexander of his apprehension and met him with valuable presents, placing himself and all his forces at Alexander's disposal.[7] Alexander not only returned Aambhi his title and the gifts but he also presented him with a wardrobe of "Persian robes, gold and silver ornaments, 30 horses and 1000 talents in gold".[7][8][9] Alexander was emboldened to divide his forces, and Aambhi assisted Hephaestion and Perdiccas in constructing a bridge over the Indus where it bends at Hund (Fox 1973), supplied their troops with provisions, and received Alexander himself, and his whole army, in his capital city of Taxila, with every demonstration of friendship and the most liberal hospitality.[10][11][2][12]

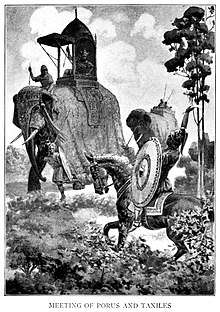

On the subsequent advance of the Macedonian king, Ambhi accompanied him with a force of 5000 men and took part in the Battle of the Hydaspes. His brother was killed by Porus. After that victory he was sent by Alexander in pursuit of Porus, to whom he was charged to offer favourable terms, but narrowly escaped losing his life at the hands of his old enemy. Subsequently, however, the two rivals were reconciled by the personal mediation of Alexander; and Ambhi, after having contributed zealously to the equipment of the fleet on the Hydaspes, was entrusted by the king with the government of the whole territory between that river and the Indus.[13][11] Post reconciliation with King Porus, Aambhi married his daughter to the son of Porus, Malayketu.[14] A considerable accession of power was granted him after the death of Philip, son of Machatas; and he was allowed to retain his authority at the death of Alexander himself (323 BC), as well as in the subsequent partition of the provinces at Triparadisus, 321 BC.[15][16][17]

Plutarch, giving an exaggerated estimate of the size of the realm of Aambhi, says that it was "as large as Egypt, with good pasturage, too, and in the highest degree productive of beautiful fruits".[18] Strabo refers to its "most excellent laws" and speaks of it as spacious and very fertile, adding that "some say that this is larger than Aegypt."[8]

Notes

- Waldemar Heckel (2002). The Wars of Alexander the Great, 336-323 B.C. Taylor & Francis. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-415-96855-3.

- Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca, xvii. 86

- Curtius Rufus, Historiae Alexandri Magni, viii. 12

- Sastri 1988, p. 55.

- Sastri 1988, p. 46.

- Jonathan Mark Kenoyer; Kimberly Burton Heuston (1 October 2005), The Ancient South Asian World, Oxford University Press, p. 110, ISBN 978-0-19-522243-2

- Sastri 1988, p. 56.

- Sastri 1988, p. 36.

- Quintus Curtius Rufus,

- Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri, iv. 12, v. 3, 8

- Curtius, viii. 14, ix. 3

- Plutarch, Parallel Lives, "Alexander", 59, 65

- Arrian, v. 8, 18, 20

- https://books.google.co.in/books?id=UQJTek1salEC&pg=PA109&lpg=PA109&dq=porus+ambhi+marriage+alliance&source=bl&ots=kLLyHgsook&sig=ACfU3U3ZSb5YaqVC2cKfe7vXEpWpoAiF0Q&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjsrqX47YXqAhXDWisKHe7MA2EQ6AEwCnoECAcQAQ#v=onepage&q=porus%20ambhi%20marriage%20alliance&f=false

- Photius, Bibliotheca, cod. 82, cod. 92

- Diodorus, xviii. 3, 39

- Justin, Epitome of Pompeius Trogus, xiii. 4

- Sastri 1988, p. 35.

References

- Robin Lane Fox, 1973. Alexander the Great, Chapters 24 ff

- Sastri, K. A. Nilakanta, ed. (1988) [1967], Age of the Nandas and Mauryas (Second ed.), Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-0465-1

- Smith, William (editor) 1867. Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, "Taxiles (1)", (Boston)

![]()