Omnilingual

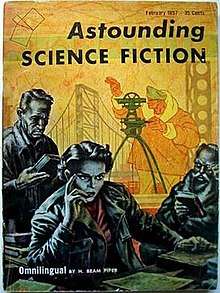

"Omnilingual" is a science fiction short story by American writer H. Beam Piper.[1] Originally published in the February 1957 issue of Astounding Science Fiction,[2] it focuses on the problem of archaeology on an alien culture.[3]

Synopsis

An expedition from Earth to Mars discovers a deserted city, the remains of an advanced civilization that died out 50,000 years before. The human scientists recover books and documents left behind, and are puzzled by their contents. Earnest young archeologist Martha Dane deciphers a few words, but the real breakthrough comes when the team explores what appears to have been a university in which the last few civilized Martians made their last stand. Inside, they find a "Rosetta Stone": the periodic table of the elements. The story builds tension from the skepticism of the rest of the team, mostly male, as well as from Dr. Dane's competitive, spotlight-seeking teammate, Tony Lattimer.

Themes

The point of the story, reflected in the title, is that science is an "omnilingual", or "all language" text. Translations of "dead" languages tend to rely on "bilingual" texts where the same message is written in both the dead language and a known language, allowing deduction of the meaning of symbols in the dead language by finding the corresponding symbols in the known language. The Rosetta Stone, for instance, contains texts in ancient hieroglyphs, a later developed Egyptian script, and ancient Greek.

As the story points out, even pictures with captions are not necessarily helpful, giving the example of a picture of a man using a hand saw. The caption could mean anything from "man sawing wood" to "Kaiser Wilhelm in exile".

In the story, Martian is discovered to be somewhat like German, in that words are constructed from other words. It is also regular and free of loanwords, unlike English. Thus in German the words for hydrogen ("Wasserstoff"), carbon ("Kohlenstoff"), nitrogen ("Stickstoff"), and oxygen ("Sauerstoff"), contain a common root word. In Martian the archaeologists quickly identify root words meaning "matter" or "element", and also "metal" by deciphering the names of elements in the Martian version of the periodic table. They encounter words such as "Of-metal-matter-knowledge", which can only mean "metallurgy". The table also gives them a clear understanding of the Martian number system, because it is arranged in a known way based on numbers. They then deduce that the Martian calendar divided the year into ten periods named for the numbers 1 to 10, and are able to identify scientific journals by their publication date.

Stylometric study

In 2018, Tomi S. Melka and Michal Místecký carried out a complex quantitative analysis of the style of H. Beam Piper's novelette (1957).[4] A number of indexes – covering the spheres of vocabulary richness, narrative speed, and cohesion – have shown that Piper’s writing is very dynamic, as verbs prevail by far over adjectives. On the other hand, discrepancies were found in the domain of lexical richness, where chapters 4 and 14 manifest lower figures than the others; this may be due to their character, or to a pause Piper might have taken in writing. This corresponds to the fact that chapter 14 abounds in long, technical expressions, which tend to be repeated throughout this portion of the text. In that way, the section contrasts with the preceding one, where the high proportion of hapax legomena (41%) may indicate the point where the story undergoes an important change; at the same time, this portion of texts contains a lot of speculative statements, as is attested by the elevated use of the definite article "the". Its employment implies that the same entity is treated from multiple viewpoints. As to the cohesion of text, the case analyses have manifested low values in case of chapter 2, which points out its complex character (descriptions, dialogues, prominent use of logical coherence, etc.). To sum up, H. Beam Piper's novelette manifests both what can be called features of modern prose (elevated use of verbs, coherence at the expense of cohesion), and the traits of academic writing (especially in chapters 4 and 14). The combination of the two makes it a good example of science fiction literature.

Publication history

Omnilingual has been reprinted several times since its original publication.

- Prologue to Analog (1962, Doubleday)

- Analog Anthology (1965, Dobson)

- Great Science Fiction Stories About Mars (1966, Fredrick Fell)

- Apeman, Spaceman (1968, Doubleday)

- Mars, We Love You (1971, Doubleday) - Also published under the title The Book of Mars

- Where Do We Go from Here? (1971, Doubleday)

- The Days After Tomorrow (1971, Little Brown)

- Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow... (1974, Rinehart & Winston)

- Science Fiction Novellas (1975, Scribner)

- Federation (1981, Ace)

- Isaac Asimov Presents The Great SF Stories 19 (1957) (1989, DAW)

- The World Turned Upside Down (2005, Baen)

References

- Piper, Henry (1957). Omnilingual. General Books.

- Walton, Jo (5 March 2012). "Scientific Language: H. Beam Piper's "Omnilingual"". Tor.com. Retrieved 28 March 2012.

- Wilkins, Alasdair. "Digging Deep: 24 Science Fiction Archaeologists". Io9. Retrieved 28 March 2012.

- Melka, Tomi S.; Místecký, Michal (2019). "On Stylometric Features of H. Beam Piper's "Omnilingual"". Journal of Quantitative Linguistics: 1–40. doi:10.1080/09296174.2018.1560698.

External links

- Omnilingual title listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Omnilingual at Project Gutenberg

- Omnilingual title listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database