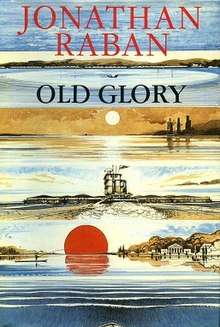

Old Glory: An American Voyage

Old Glory is a travel book by Jonathan Raban. It is the winner of The Royal Society of Literature's Heinemann Award and the Thomas Cook Travel Book Award.

First edition | |

| Author | Jonathan Raban |

|---|---|

| Publisher | William Collins |

Publication date | 1981 |

| ISBN | 0-330-29229-3 |

| OCLC | 15664455 |

Plot summary

Old Glory describes Raban's voyage down the Mississippi River in a 16-foot aluminium "Mirrocraft" powered by a 15 h.p. Johnson outboard engine. Inspired by his reading of Mark Twain's Adventures of Huckleberry Finn as a seven-year-old boy living in Norfolk, in which his local stream is transformed into the Mississippi Valley in his imagination, Raban sets out on his own personal journey thirty years later.

It is in this book that the author develops his own unique writing style (starting to emerge in Arabia Through the Looking Glass), with highly descriptive scenes of the landscape that he passes through, as well as ironic but highly incisive descriptions of the characters he meets along the way. This style is more fully developed in his later travelogues: Coasting (book), Hunting Mister Heartbreak: A Discovery of America and Passage to Juneau: A Sea and Its Meanings.

Plot

Minneapolis to St Louis

Raban's journey starts out in Minneapolis, 200 miles down from the Mississippi's source at Lake Itasca. The author feels a great deal of trepidation when he first takes out his skiff on the water, and has a quick two-hour instruction course from Herb Heichert, the friendly owner of Crystal Marine from whom he borrows the boat. He tells Raban to turn the prow of his boat into the stern wave of the huge passing tugs or towboats working the Mississippi, to watch out for floating logs and to avoid the wing-dams jutting out from the river's banks. After this crash course in river navigation, Raban then has to navigate his way through Lock No. 1, the first of twenty-six huge locks between Minneapolis and St Louis.

After a few days' cruising, the author starts to settle down and is able to take time out smoking on his corn cob pipe filled with pungent Captain Black. He stops off each night at one of the small towns lining the river: Red Wing, Lansing, Dubuque, Bellevue, Clinton, Nauvoo, Hannibal, etc. Most of them are all rather alike, with their run-down genteel shabbiness and old disused button-making factories that first arose with the decline of the river boats, following the introduction of the diesel engine. Many of the towns' inhabitants he encounters along the way are either down-to-earth farmers who still retain their sense of community through events like Saturday pig roasts, or alcoholic wealthier individuals whose lives continue to focus on their children, even though they have grown up and fled the nest in their desire to escape their small decaying hometowns.

He experiences a series of misadventures on the river itself, having to fortify himself with slugs of Jack Daniel's straight from the bottle. The worst occurs when the keeper of Lock 17 advises him to drive his boat at night and he is nearly run down by the wake of a tow, which catches his skiff broadside. Once the Missouri River joins the Mississippi, the river's character becomes more venomous; Raban now has to avoid the huge whirlpools, boils and shoaling created by the force of the two rivers' powerful struggle to become one. The author also has two romantic adventures during the first half of his often very lonely voyage—one with Judith, a teacher in Muscatine, and the other with Sally, a neurotically disorganized but highly affectionate American Jewish woman, with whom he lives for a short time in a suburb of St Louis. Over their final dinner together at the most expensive restaurant in Clayton, she calls him a 'coward' for leaving her to continue his voyage downstream. St Louis itself is a great disappointment for the author who remains unimpressed by efforts to revive the city through its convention center. He goes to the top of the Gateway Arch but all he can see ahead of him is a giant wasteland and the Mississippi itself looks like 'an open drain which had taken on the St Louis colours of rust, soot and rotting brick'.

St Louis to New Orleans

It is now Halloween. On the strong advice of a more experienced sailor, a construction engineer from Chicago, Raban buys a $380 marine radio for communicating directly with the larger and much more powerful tugs ploughing up and down the river as well as for emergency use, admitting to his own naivety at not having obtained one earlier. Raban meets Ted and his family traveling on their 30-something-foot sloop, Morning Star out of Chicago, who, like him, are hooked on traveling, making a similar journey that also arouses the same feeling of envy in people when they hear about it.

Now that he is in the lower river, the atmosphere changes and before he reaches Memphis, Raban admits to being depressed by the river, giving a strong insight into the nature of the beast:

On Brandywine Chute I was depressed by the Mississippi in a way I hadn't been before. I feared its emptiness and loathed its enormous cargo of dead matter, the jungly shore, the purulent, inflamed water.

He feels cheered up on reaching Memphis and tracks the local mayoral election between a new hope, the black reverend judge, Otis Higgs, against the white incumbent. Becoming a part of Higgs's campaign team, the author encounters the strong race divisions in the city and his charismatic candidate's efforts ultimately end in failure. Raban leaves Memphis on board a tow, the Frank Stegbauer, pushing nine barges loaded with twelve million dollars' worth of ammonia. After sharing his Thanksgiving dinner with the crew and being congratulated by its Cap on his novice piloting skills, he is eventually offloaded above Vicksburg. After a short trip to Natchez, he is taken on another tow, the Jimmie L., to New Orleans, whose garish tourist-focused vitality proves a huge disappointment.

Wanting to escape the false 'magic of the city', he looks for the end of his journey in the old floodways south of New Orleans. Traveling along the Intracostal Waterway, he is struck by the lusciousness of the vegetation around him, and the slow, meandering lifestyle of its Cajun inhabitants. After a final stop-over in deadbeat Morgan City and its fly-bitten motel, he reaches his journey's end in the seaward neck of Bayou Shaffer:

It was rich water. Dark with peat, thickened with salt, it was like warm soup. When the first things crawled out of the water, they must have come from swamp like this one, gingerly testing the mud with their new legs. I trailed my hand over the gunwale and licked my wet forefinger. It tasted of salt.

Sources

- Old Glory, Jonathan Raban, William Collins (1981)