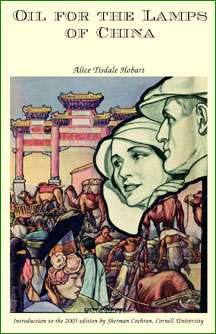

Oil for the Lamps of China

Oil for the Lamps of China is a 1933 novel by Alice Tisdale Hobart which became a bestseller in 1934. It was originally published by Bobbs Merrill and reprinted by EastBridge in 2002 (ISBN 1891936085).[1]

| |

| Author | Alice Tisdale Hobart |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Subject | American business in early 20th century China |

| Set in | China |

| Published | 1933 |

| Publisher | Bobbs-Merrill, EastBridge |

Publication date | 2002 |

- For the business catchphrase, see Freebie marketing#Standard Oil

The novel describes the life in China of a young executive in an American oil company from the early 1900s through the Nationalist Revolution of the 1920s. The young protagonist, Stephen Chase, is successful in understanding China and building business, but in the turmoil of China's Nationalist Revolution of the 1920s, he is betrayed by the company and by the new China which emerges. Hobart's husband was an executive for the Standard Oil Company.[2]

The novel was the basis of a 1935 film by the same name starring Pat O'Brien.[3]

Reception

The author Emily Hahn wrote in the Shanghai journal T'ien Hsia in the mid-1930s that "unfortunately" Hobart "seems to share a strange idea of the public’s that all persons whose skin-pigmentation differs from ours must use a bastard eighteenth-century Biblical sort of elocution." Hahn continues:

- I grant that her portrayal of Western business methods in contact with the East is excellent. Only, this insistence upon Chinese peculiarities is misleading, taking us away from the ultimate truth that these differences are traceable not to some occult inheritance, but to tradition and training and environment....

- This is a pity in Oil for the Lamps of China. Nobody else has given us such realistic portrayals of very familiar types; the amah, the house-boy, the manager’s wife, queen of the hong. [4]

A review called the 2002 reprint "timely" because "the atmosphere which greets the foreign businessperson in coastal China today closely mirrors that of Shanghai in the 1930s," and that Hobart was "especially good at conveying that first-time Marco Polo-like feeling of discovery that China still communicates to the uninitiated Western sojourner." These insights are conveyed in "down-to-earth non-academic" language.[5]

Notes

- Eastbridge Books.com Accessed 5 February 2015. (http://www.eastbridgebooks.org/oil_info.html)

- GoodReads.com Accessed 5 February 2015 (http://www.goodreads.com/book/show/2145899.Oil_for_the_Lamps_of_China)

- Sennwald, Andre. "Oil for the Lamps of China." New York Times, 6 June 1935. (https://www.nytimes.com/movies/movie/104545/Oil-for-the-Lamps-of-China/overview)

- Hahn (1936).

- MacKinnon (2004), p. 528.

References

- Cochran, Sherman (2013). "Alice Tisdale Hobart's Dark Novel of American Capitalism and Chinese Revolution". Journal of American-East Asian Relations. 20 (1): 69–78. doi:10.1163/18765610-02001010.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hahn, Emily (1936). "The China Boom". T'ien Hsia Reprinted China Heritage Quarterly #22 June 2010.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- MacKinnon, Stephen R. (2004), "Review", Pacific Affairs, 77 (3): 568–570, JSTOR 40022931CS1 maint: ref=harv (link).

- T. Barrett, "Review," Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 67.1 (February 2004), pp 124–126.