Odoardo Ceccarelli

Odoardo Ceccarelli (c. 1600 – 7 March 1668) was an Italian singer, composer, and writer prominent in the Sistine Chapel Choir and the Barberini court. Described from the beginning of his career as both a tenor and a bass, he created roles in several operas, including Fileno in Michelangelo Rossi's Erminia sul Giordano and Orlando in Luigi Rossi's Il palazzo incantato.

Odoardo Ceccarelli | |

|---|---|

| Born | c. 1600 Bevagna, Italy |

| Died | 7 March 1668 Rome, Italy |

| Occupation |

|

| Relatives | Alfonso Ceccarelli (grandfather) |

Life and career

Ceccarelli was born in Bevagna. His father Pannonio was a meat carver.[lower-alpha 1] His grandfather Alfonso was a notorious doctor and genealogist who was executed in 1581 for falsifying documents. The first record of his activity in Rome is from 1620 when he was listed as a choir member at the church of Santo Spirito in Sassia. In 1622 he entered the Collegium Germanicum. He remained resident there for a year, but continued to sing in the choir of Sant'Apollinare, the Collegium's church, on multiple occasions up to 1645. During his time with the choir he trained with Giacomo Carissimi who trained several other prominent Roman singers, including Giuseppe Bianchi and the castrato Giovannino.[2][3][lower-alpha 2] Ceccarelli was also considered an outstanding interpreter of Carissimi's motets which they often performed together.[5]

Ceccarelli was appointed to the Sistine Chapel Choir in January 1628. He later served as the choir's chamberlain (camerlengo) in 1630 and its secretary (puntatore) in 1647. He was appointed maestro di cappella in 1652. In addition to his activities with the Papal choir, Ceccarelli sang in the festivities in Parma celebrating the marriage of Margherita de' Medici and Odoardo Farnese in 1628 as well as at the court of Ferdinando II in 1635 and at the church of San Luigi dei Francesi on several occasions between 1631 and 1653. He also sang in five operas performed in Rome between 1633 and 1645.[2][6][7]

From the earliest years of his career Ceccarelli was described in some records as a tenor and in others a bass.[8] The musicologist Alberto Iesuè has speculated that his true voice type was probably a bass and that he sang tenor parts in falsetto.[2] However, in Tenor: History of a Voice, John Potter refers to a type of voice with an extended register which he calls "tenor-bass" and notes that several other virtuoso singers of the 17th century who were described as tenors by their contemporaries could also sing in the bass register. A similar view on the existence of this voice type has been expressed by Rodolfo Celletti.[9][10]

Ceccarelli retired from the Sistine Choir in 1658. He spent his later years as a prominent member of the Confraternity of the Most Holy Crucifix and served as maestro di cappella of its associated church, San Marcello, until 1667. He died on 7 March 1668. His funeral was held two days later at Santa Maria Maddalena. In his will, he left most of his money and possessions to the confraternity.[6][11] According to his entry in the Großes Sängerlexikon, Ceccarelli had become a priest in 1641. In his 1710 history of the Sistine Chapel Choir, Andrea Adami refers to him as "Rev. Odoardo Ceccarelli".[12][13]

Compositions and writings

Ceccarelli composed several pieces of music, including a lyric drama in Latin for four sopranos and chorus, an idyll in Italian for five voices, and a cantata for soprano and bass, Ecco il re del cielo immenso. However, the only extant score is Ecco il re del cielo immenso, which is held in the Biblioteca Casanatense. In 1634, at the request of Pope Urban VIII, he began work with Sante Naldini,[lower-alpha 3] Stefano Landi, and Gregorio Allegri to adapt the vocal music of older breviaries and to improve and annotate the texts of Palestrina's vocal music. The result of their work, Hymni Sacri in Breviario Romano, was published in 1644.[6][2]

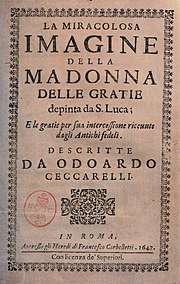

Described by Adami, Liberati, and Fétis as an erudite man of letters and an excellent writer of poetic texts for music in both Latin and Italian, Ceccarelli also authored two prose works on images of the Virgin Mary in Rome, both published in 1647.[7][13][15] La miracolosa imagine della Madonna delle Gratie depinta da S. Luca describes an image of Mary in Santa Maria della Consolazione purportedly painted by Saint Luke and the miracles associated with it. Breve racconto della manifestatione della devotissima imagine della santissima Vergine describes the restoration of a fresco depicting Mary in the portico of Sant'Apollinare which survived the Sack of Rome in 1527 because the priests had it plastered over to hide it from the invaders.[16][17]

Opera performances

- Erminia sul Giordano (as Fileno), composed by Michelangelo Rossi to a libretto by Giulio Rospigliosi, performed at the Palazzo Barberini, Rome, 1633[18]

- Santa Teodora by an anonymous composer to a libretto by Giulio Rospigliosi, performed at the Palazzo Barberini, Rome, 1635[6][19]

- La sincerità trionfante composed by Angelo Cecchini[lower-alpha 4] to a libretto by Ottaviano Castelli,[lower-alpha 5] performed at the palazzo of François Annibal d'Estrées, Rome, 1638[12][22]

- Il palazzo incantato (as Orlando) composed by Luigi Rossi to a libretto by Giulio Rospigliosi, performed at the Palazzo Barberini, Rome, 1642[18]

- Il ratto di Proserpina by an anonymous composer to a libretto by Pompeo Colonna,[lower-alpha 6] performed at the palazzo of Pompeo Colonna principe di Gallicano, Rome, 1645[12][24]

Notes

- In 1607 Pannonio Ceccarelli achieved a fame of sorts as the subject of a miracle attributed to St. Philip Neri. According to contemporary accounts, he was languishing in prison in Perugia for a crime he did not commit when his brother, a priest living in Rome, prayed with another priest at Neri's tomb for Pannonio's release. The second priest also said a mass on 14 October 1607, again asking for Neri's intercession. Five days later, Pannonio wrote to his brother that on 14 October he had found the keys of the prison in a place where he had never thought to look, opened the prison doors, and walked out. Although he had passed both the judge and the chief notary and saluted them on his way out, neither one had said a word to him. It was later discovered that although Pannonio had not actually committed the crime in question, he had been an accomplice. Pope Paul V subsequently granted him a pardon.[1]

- In 1647 Cardinal Friedrich of Hesse-Darmstadt made an unsuccessful attempt to persuade Carissimi, Ceccarelli, Bianchi, and Giovannino to leave Rome and enter into the service of Archduke Leopold Wilhelm of Austria.[4]

- Sante Naldini (1588–1666) was a composer of sacred music, a tenor in the Sistine Chapel Choir, and later an abbot.[14]

- Angelo Cecchini, was a composer active in Rome from 1619 to 1639. He was the maestro di cappella of Santa Maria della Consolazione and later a musician at the court of Paolo Giordano Orsini. He composed four operas, all to librettos by Ottaviano Castelli and all performed in Rome.[20]

- Ottaviano Castelli (c. 1602–1642) had doctorates in both law and medicine, but was primarily known for his work as an amateur librettist, scene painter and composer. A member of Maffeo Barberini's circle, he organized numerous spectacles for him in Rome. Eight operas composed to his librettos had been performed by 1639.[21]

- Pompeo Colonna principe di Gallicano (c. 1600–1658) was a wealthy nobleman and a member of the Zagarolo branch of the Colonna family. A poet, patron of the arts, and a member of several academies, Colonna wrote Il ratto di Proserpina in honour of Olimpia Maidalchini, the sister-in-law of Pope Innocent X.[23]

References

- Bacci, Pietro Giacomo (1847). The Life of Saint Philip Neri, Apostle of Rome, and Founder of the Congregation of the Oratory, Vol. 2, pp. 325–326. T. Richardson & Son (English translation of the original Italian text published by Pietro Giacomo Bacci in 1646, Vita di S. Filippo Neri fiorentino fondatore della Congregatione dell'Oratorio)

- Iesuè, Alberto (1979). "Ceccarelli, Odoardo". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Vol. 23. Treccani. Online version retrieved 2 November 2018 (in Italian).

- Kory, Agnes (1995). "Leopold Wilhelm and His Patronage of Music with Special Reference to Opera". Studia Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, Vol. 36, pp. 11-25. Retrieved 6 November 2018 (subscription required).

- Frandsen, Mary E. (2006), Crossing Confessional Boundaries: The Patronage of Italian Sacred Music in Seventeenth-Century Dresden. p. 24. Oxford University Press. ISBN 019534636X

- Fantoni, Gabriele (1873). Storia universale del canto, Vol. 1, p. 145. Natale Battezzati (in Italian)

- Centre de Musique Baroque de Versailles. Musiciens à Rome de 1570 à 1750: "Ceccarelli, Odoardo". Retrieved 2 November 2018 (in Italian).

- Rambotti, Fiorella (2008). La musica è una mera opinione e di questa non si può dar certezza veruna, pp. 82, 102. Morlacchi Editore. ISBN 8860742021 (in Italian)

- Murata, Margaret (2001). "Ceccarelli, Odoardo". The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 2nd edition. Online version retrieved 2 November 2018 (subscription required for full access).

- Celletti, Rodolfo (1989). Voce di tenore, p. 19. IdeaLibri. ISBN 8870821277

- Potter, John (2009). Tenor, History of a Voice, pp. 17-18. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300168934

- Lionnet, Jean 1985). La musique à Saint-Louis des Français de Rome au XVIIe siècle, p. 80. Edizioni Fondazione Levi. Retrieved 6 November 2018 (in French).

- Kutsch, Karl-Josef and Riemens, Leo (2012). "Ceccarelli, Odoardo". Großes Sängerlexikon 4th edition, Vol. 1, p. 781. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 359844088X (in German).

- Adami, Andrea (1710). Osservazioni per ben regolare il Coro de i Cantori della Cappella Pontificia, p. 197. Antonio de' Rossi (in Italian)

- Champlin, John Denison and Apthorp, William Foster (1888). "Naldini, Sante". Cyclopedia of Music and Musicians, Vol. 3, p. 4. Charles Scribner's Sons

- Fétis, François-Joseph (1837). "Ceccarelli, Édouard". Biographie universelle des musiciens, Vol. 3, pp. 87–88. H. Fournier (in French)

- Ceccarelli, Odoardo (1647). La miracolosa imagine della Madonna delle Gratie depinta da S. Luca. Corbelletti (in Italian)

- Ceccarelli, Odoardo (1647). Breve racconto della manifestatione della devotissima imagine della santissima Vergine nel portico della chiesa di S. Apolllinare in Roma il di 13 Febraro 1647. Barberi (in Italian)

- Casaglia, Gherardo (2005). "Odoardo Ceccarelli". Almanacco Amadeus. Retrieved 2 November 2018 (in Italian).

- Smither, Howard E. (2012). A History of the Oratorio, Vol. 1, p. 157. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0807837733

- Murata, Margaret (2001). "Cecchini, Angelo". The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 2nd edition. Online version retrieved 6 November 2018 (subscription required for full access).

- Bianconi, Lorenzo and Murata, Margaret (2001). "Castelli, Ottaviano". The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 2nd edition. Online version retrieved 6 November 2018 (subscription required for full access).

- Murata, Margaret (July 1995). "Why the First Opera Given in Paris Wasn't Roman". Cambridge Opera Journal, Vol. 7, No. 2, pp. 87-105. Retrieved 2 November 2018 (subscription required).

- Petrucci, Franca (1982). "Colonna, Pompeo". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Vol. 27. Treccani. Online version retrieved 6 November 2018 (in Italian).

- Archive of Performances of Greek and Roman Drama. "Il ratto di Proserpina (1645)". Retrieved 2 November 2018.