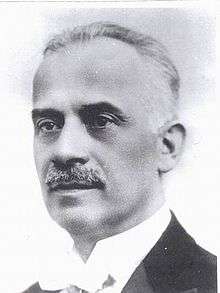

Octavian Codru Tăslăuanu

Octavian Codru Tăslăuanu (February 1, 1876 – October 22, 1942) was an Austro-Hungarian-born Romanian magazine publisher, non-fiction writer and politician.

Octavian Codru Tăslăuanu | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | February 1, 1876 |

| Died | October 22, 1942 (aged 66) |

| Burial place | Bellu Cemetery |

| Nationality | Austro-Hungarian, later Romanian |

| Alma mater | University of Bucharest |

| Occupation | magazine publisher, author, politician |

| Political party | Romanian National Party People’s Party (after 1920) |

| Spouse(s) | Adelina Olteanu ( m. 1906) |

Biography

Background and early life

Born in Bélbor, Maros-Torda County, now Bilbor, Harghita County, his parents were Ion, a Greek-Catholic priest and member of a clerical family; and Anisia (née Stan), a local peasant woman.[1] The upper Mureș region, centered at Toplița, had been part of Moldavia before being annexed by the Habsburg Monarchy in 1775, and Ion would remind his son that the family was of Moldavian origin.[2] The family name refers to the valley of the Tazlău River, where it lived prior to arriving in the Toplița area.[3] The second of eleven children, Octavian started primary school in his native village before the age of five. From 1884 to 1889, he went to primary school in Gheorgheni. In autumn 1889, he enrolled in the Romanian high school at Năsăud.[1] In 1890, he started at Brașov's Romanian high school, leaving for the Blaj high school in 1892. While there, in 1894, he was an active participant at the protests in support of the Transylvanian Memorandum.[4]

In December 1895, he passed his baccalauréat at Năsăud, subsequently taking employment as a notary in Bicaz, in the Romanian Old Kingdom. In 1896, he was a teacher in Craiova, while the following year, he was drafted into the Austro-Hungarian Army and sent to serve at Trieste. Following examinations, he was made a second lieutenant in the reserves.[4] From 1898 to 1902, he studied at the Literature and Philosophy faculties of the University of Bucharest, and his professors included Titu Maiorescu, Nicolae Iorga, Ovid Densusianu and Simion Mehedinți. A good student, he obtained a prize from the Carol I Academic Foundation for a work on the origins of the Hunyadi family.[5]

Luceafărul and war experience

In 1902, Tăslăuanu was named a secretary at the Romanian consulate in Budapest.[6] Somewhat unusually for a member of the country's diplomatic service, he did not hold Romanian citizenship at the time.[7] While there, he edited and corrected articles for Luceafărul, as well as writing original work, and began a close friendship with Octavian Goga, for whom he managed to create an environment that fostered Goga's poetic creativity. The following year, he became head editor at the magazine, which due to his initiative emerged as a voice for younger writers, in particular Goga, then reaching the peak of his creativity.[6] By 1904, he was owner as well as editor of Luceafărul. In 1905, he attended celebrations at Sibiu marking the opening of the ASTRA Museum. There, he met Adelina Olteanu, a former Luceafărul contributor whom Goga intended to marry. She and Tăslăuanu fell in love and became engaged, marking the first break with Goga. On June 17, 1906, the couple married, and that year, he moved the Luceafărul headquarters from Budapest to Sibiu, the first issue appearing there in October. Also that autumn, he became administrative secretary of ASTRA,[8] as well as signing a contract stipulating Goga would be director of Luceafărul and Tăslăuanu editor-in-chief.[9]

By 1907, the magazine was thriving in Sibiu, and Tăslăuanu became among the first journalists to write about Constantin Brâncuși, realizing the value of the latter's artistic output and going on to print a number of images depicting his sculptures. In 1909, he took on the publication of Transilvania as well. The following year, he suffered a heavy blow when his wife died at the age of 33; she had been a close collaborator.[10] In 1911, he reorganized the ASTRA library, publishing science and culture brochures under its name. He was also a dedicated director of the association's museum, bringing in numerous ethnographic exhibits. Between 1911 and 1912, he published a calendar for ASTRA, while he made up with Goga, so that the latter returned to Luceafărul as director. In 1914, with the outbreak of World War I, he was sent to the front and his cultural activities were put on hold. However, he did manage to publish two books about his war experiences, in 1915 and 1916.[11] At first, he served in the Austro-Hungarian Army, as part of a Făgăraș-based Royal Hungarian Honvéd battalion.[12] He subsequently deserted and, following Romania's entry into the war in 1916 on the side of the Allies, he enrolled in the Romanian Land Forces as a volunteer.[13]

Politics and later writings

In 1918, following the union of Transylvania with Romania, Tăslăuanu was elected a member of the Great Romanian National Council by the assembly at Alba Iulia that approved the union. He also remarried; his new wife was Fatma Sturdza, whom he met on the front as a nurse. In 1919, he was elected to the Chamber of Deputies for the Tulgheș seat. Also elected vice president of the Romanian Writers' Society, he moved Luceafărul to Bucharest and founded a publishing house in Cluj. In 1920, he held two ministerial posts: Commerce and Industry (March 13-November 16) and Public Works (November 16-December 31). He resigned due to vehement attacks from the National Liberal Party-dominated press.[14] Initially a member of the Romanian National Party, in 1920, persuaded by Goga, he joined Alexandru Averescu's People's Party and served in the latter's cabinet.[15]

While in government, Tăslăuanu used his expertise in economics and Transylvanian affairs to help craft a land reform law for the province. His interest in economics continued after leaving office and into the Great Depression; ideologically, his views fell into the classical liberal camp. He believed the state should remain uninvolved in commerce, production or industry, and that its efforts tended to kill off individual initiative.[16] In 1926, he was elected to the Senate for Mureș County. Meanwhile, he published a series of books between 1924 and 1939: on politics, economics, the national movement in Transylvania, reflections on the Luceafărul era,[17] and finally, in 1939, his last important work appeared, presenting his memories of the recently deceased Goga.[18] In 1941, he founded the weekly magazine Dacia in Bucharest; this appeared from April 15 to May 1. The following year, he published an article on the occasion of the 40th anniversary of Luceafărul; it was to be the last work of his that appeared during his lifetime. He died of respiratory failure and was buried in Bellu cemetery.[19] There is a high school in Toplița that was named after him in 1990.[20]

Tăslăuanu as a younger man

Tăslăuanu as a younger man- The Bilbor Wooden Church, where Tăslăuanu's father served as priest[21]

Goga's "Învins" ("Defeated"), printed in Luceafărul in March 1905

Goga's "Învins" ("Defeated"), printed in Luceafărul in March 1905 Brâncuși's Bust of a Boy, as it appeared in Luceafărul in February 1908

Brâncuși's Bust of a Boy, as it appeared in Luceafărul in February 1908

Notes

- Ţipu, p.7

- Tăslăuanu, pp.vi, 14

- Netea, p.12

- Ţipu, p.8

- Ţipu, p.8-9

- Ţipu, p.9

- (in Romanian) Andreea Dăncilă, "Ipostaze ale elitei culturale româneşti din Transilvania începutului de secol XX: generaţia Luceafărului (1902-1914)", p.230, in the December 1 University of Alba Iulia's Series Historica Archived 2013-01-14 at the Wayback Machine, 14/I, 2010

- Ţipu, p.10

- Ţipu, pp.10–11

- Ţipu, p.11

- Ţipu, p.12

- (in Romanian) Constantin I. Stan, "Viața în tranșee în anii Primului Război Mondial (1914-1918)", p.78, in Analele Universității Dunarea de Jos din Galați, Seria Istorie, 9/2010

- Netea, p.24

- Ţipu, p.13

- (in Romanian) Zigu Ornea, "Publicistica lui Goga", in România Literară, Nr. 2/1999

- (in Romanian) Petre Poruțiu, "Octavian C. Tăslăuanu Economist", in Luceafărul, Nr. 12/1942, p.440-42 (digitized by the Babeş-Bolyai University Transsylvanica Online Library)

- Ţipu, p.14

- Ţipu, p.15

- Ţipu, p.16

- Short history at the O. C. Tăslăuanu Theoretical High School site

- Tăslăuanu, p.40

References

- (in Romanian) Vasile Netea, "Mureșul superior: vatră de cultură românească", Editura Cuvântul, Bucharest, 2006, ISBN 978-973-99882-6-1

- Octavian C. Tăslăuanu, Spovedanii. Editura Minerva, Bucharest, 1976

- (in Romanian) Corina Ţipu, "Octavian C. Tăslăuanu", Seria Personalia, nr.15, Biblioteca Judeţeană ASTRA, Sibiu, 2007

External links