Nzinga of Ndongo and Matamba

Nzingha Mbande (1583–1663) was Queen of the Ambundu Kingdoms of Ndongo (1624–1663) and Matamba (1631–1663), located in present-day northern Angola.[1] Born into the ruling family of Ndongo, Nzinga received military and political training as a child, and she demonstrated an aptitude for defusing political crises as an ambassador to the Portuguese Empire. She later assumed power over the kingdoms after the death of her father and brother, who both served as kings. She ruled during a period of rapid growth in the African slave trade and encroachment of the Portuguese Empire into South West Africa, in attempts to control the slave trade.[2] Nzinga fought for the freedom and stature of her kingdoms against the Portuguese[1] in a reign that lasted 37 years.

| Queen Ana Nzinga | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Born | c. 1583, Angola | ||||

| Died | December 17, 1663 (aged 79–80) | ||||

| |||||

| House | Guterres | ||||

| Father | Ngola Kilombo Kia Kasenda | ||||

| Mother | Kangela | ||||

In the years following her death, Nzinga has become a historical figure in Angola. She is remembered for her intelligence, her political and diplomatic wisdom, and her brilliant military tactics. A major street in Luanda is named after her. In 2002, a statue of her in Largo do Kinaxixi, Luanda, Angola, was dedicated by then-President Santos to celebrate the 27th anniversary of independence.

Early life

Nzinga was born into the royal family of Ndongo in central West around 1583. She was the daughter of Ngola (King) Kilombo of Ndongo. Her mother, Kengela ka Nkombe,[3] was one of her father's slave wives[4] and his favorite concubine.[3] Nzingha had two sisters: Mukumbu, or Lady Barbara and Kifunji, or Lady Grace.[5] She also had a brother, Mbandi Kiluanji, who took over the throne after their father died.

According to legend, the birth process had been very difficult for Kengela, the mother.[3] Nzinga received her name because the umbilical cord was wrapped around her neck (the Kimbundu verb kujinga means to twist or turn). It was said to be an indication that the person who had this characteristic would grow to become a powerful and proud person.[6]

When she was 10 years old, her father became the king of the Ndongo.[3] As a child, Nzinga was greatly favored by her father. Since she was not considered an heir to the throne (like her brothers), she was not seen as direct competition, so the king could freely lavish attention upon her. She received military training and was trained as a warrior to fight alongside her father. She participated in many official and governance duties alongside her father, including legal councils, war councils, and important rituals.[3] Furthermore, Nzinga was taught by visiting Portuguese missionaries to read and write in Portuguese.[7]

During this period, the kingdom of Ndongo was managing multiple crises, largely due to conflicts with the Portuguese. The Portuguese had first come to Ndongo in the late 15th century. They primarily focused on the port cities at first,[3] as part of the Atlantic slave trade and their consolidation of power in the region. However, in 1571, Sebastian of Portugal ordered the subjugation of Ndongo. The Imbangala, a group of young nomadic warriors already in conflict with Ndongo, joined forces with the Portuguese. The Imbangala wanted to seize Ndongo land, and the Portuguese wanted to claim slaves out of the crisis. The situation was worsened because many Ndongo leaders joined the Portuguese side, which reduced the manpower and tributary funds available to the king. By the time that Nzingha's father became king in 1593, the area had been at war for over 10 years. The king tried a variety of methods to handle the crisis, including diplomacy, negotiations, and open warfare, but he was unable to improve the situation.[3]

Name variations

Queen Nzinga Mbande is known by many different names including both Kimbundu and Portuguese names, alternate spellings and various honorifics. Common spellings found in Portuguese and English sources include Nzinga, Nzingha, Njinga and Njingha.[8] In colonial documentation, including her own manuscripts, her name was also spelled Jinga, Ginga, Zinga, Zingua, Zhinga and Singa.[9] She was also known by her Christian name, Ana de Sousa.[8] This name—Anna de Souza Nzingha—was given to her when she was baptised. She was named Anna after the Portuguese woman who acted as her Godmother at the ceremony. She helped influence who Nzingha was in the future.[7] Her Christian surname, de Souza, came from the acting governor of Angola, João Correia de Souza.[10]

As monarch of Ndongo and Matamba, her native name was Ngola Njinga. Ngola was the Ndongo name for ruler and the etymological root of "Angola". In Portuguese, she was known as Rainha Nzinga/Zinga/Ginga (Queen Nzingha). According to the current Kimbundu orthography, her name is spelled Njinga Mbandi (the "j" is a voiced postalveolar fricative or "soft j" as in Portuguese and French, while the adjacent "n" is silent). The statue of Njinga now standing in the square of Kinaxixi in Luanda calls her "Mwene Njinga Mbande".

Succession to power

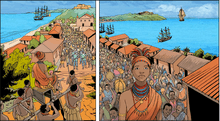

Nzinga's Embassy

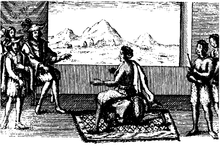

In 1617, Ngola Mbandi Kiluanji died and Ngola Mbandi, his son and Nzinga's brother, came to power.[12] As the new king, Mbandi felt paranoid that one day Nzinga’s only son (a baby) would plot to have him assassinated. So instead, he ordered her son killed. He then forcibly had Nzinga sterilized, which ensured that she would never have a child again. Perhaps fearing for her life, Nzinga fled to the Kindom of Matamba, where she stayed until her brother asked for her to return to be his ambassador to the Portuguese in 1621.[3] Her brother was failing to defeat the Portuguese and needed Nzinga's help to negotiate a treaty. She was the best fit for the job, as she spoke fluent Portuguese. Upset with the famine and terror that ravaged her home village, she agreed to meet to negotiate with Dom João Correia de Sousa, the Portuguese Governor. In 1622, Nzinga arrived in Luanda. While Ndongo leaders typically met the Portuguese in Western clothing, she chose to wear opulent traditional clothing of the Ndongo people, in order to display that their culture was not inferior. The story goes that when Nzingha arrived, there were chairs for the Portuguese individuals and only a mat provided for her. This type of behavior from the Portuguese was common; it was their way of displaying a “subordinate status, a status reserved for conquered Africans.” Nzingha's soldier formed himself to be her chair while she spoke to the governor face to face. Nzingha was a fierce negotiator who made sure to flatter the Portuguese, according to the story. She was able to reach an agreement with the Portuguese, which entailed the withdrawal of Portuguese troops from Ndongo and recognition of its sovereignty. She was also able to ensure that the Ndongo did not need to pay tributes. She did this by successfully arguing that the kingdom was an independent one, rather than a vassal or conquered state. In return, she agreed to open trade routes to the Portuguese, as well as study Christianity and become baptized.[7][3]

Consequently, Nzingha was baptized in Luanda.[13] She adopted the name Dona Anna de Sousa in honor of her godparents, Ana da Silva (the governor's wife and her godmother) and Governor de Sousa.[2][3] She sometimes used this name in her correspondence (or just Anna). Nzingha later called this period a happy time in her life, and she eventually left Luanda with the sense of a peace treaty completed.[3]

Taking over as Ruler

Following the negotiations, peace between Ndongo and Imbangala collapsed. The Ndongo were driven out of their court in Kabasa, which made the king officially in exile. The Portuguese did not want to proceed with the treaty if the king was in exile and unbaptized.[3] As a result, the Portuguese never honored the treaty and they continued to raid the kingdom, taking Africans as captives and precious items in the process. They also did not withdraw Ambaca and return the subjects, who became prisoners of war, and they were unable to restrain the Imbangala.[7]

In 1624, her brother died of mysterious causes (some say suicide, others say poisoning).[7] Before his death, he had made it clear that Nzingha should be his successor. An opulent funeral was arranged, and some of his remains were preserved in a misete (a reliquary), so they could later be consulted by Nzingha. After the death of Ngola Mbande, the Portuguese declared war on Ndongo as well as on other nearby tribes.

Nzingha had a rival, Hari a Ndongo, who was opposed to a woman ruling. Hari, who was later christened Felipe I, swore vassalage to the Portuguese. With the help of the Kasanje Kingdom and Ndongo nobility who opposed Nzingha, she was removed from Luanda. Nzingha then fled, and she kidnapped the Queen of Matamba and her army. From there, she made herself Queen and took over the kingdom. Then she returned to Ndongo and took back her throne.[4]

Nzingha used genealogy to support her claim to the throne of Ndongo against aristocratic rivals. However, neither Nzingha nor her predecessor brother had a direct right to the throne because they actually were children of slave wives, not the first wife. Nzingha strategically used the claims that she was properly descended from the main royal line because of her father, while her rivals were not at all. Her opponents, on the other hand, used other precedents to discredit her, such as that she was a female and thus ineligible.[4]

Nzingha was never able to give a credible reason for a woman to rule and she was clearly aware that being female reduced her legitimacy in the eyes of even her supporters. As a result, Nzingha adopted a more radical method of overcoming the "illegitimacy of her sex."[4] At some point in the 1640s, Nzingha decided to 'become a man', which is actually a practice many female rulers in central and western Africa used to maintain their power. Njinga reinforced this maleness by engaging in masculine pursuits. She led her troops personally in battle, and she was deft in the use of arms herself.

Dealing with the Portuguese and aligning with the Dutch

In 1641, forces from the Dutch West India Company, working in alliance with the Kingdom of Kongo, seized Luanda, and set up a directorate of Loango-Angola. Nzingha soon sent a diplomatic mission to negotiate with the Dutch. She forged an alliance with the Dutch, against the Portuguese, who continued to occupy the inland parts of their colony with their main headquarters in Massangano. With this alliance, Nzingha moved her capital to Kavanga, in the northern part of Ndongo's former domains. This move was made in the hope of recovering lost lands with Dutch help.

In 1644, Nzingha defeated the Portuguese army at Ngoleme, but was unable to follow up. Then, in 1646, she was defeated by the Portuguese at Kavanga and, in the process, her other sister was captured, along with her archives, which revealed her alliance with Kongo. These archives also showed that her captive sister had been in secret correspondence with Nzingha and had revealed coveted Portuguese plans to her. As a result of the woman's spying, the Portuguese reputedly drowned the sister in the Kwanza River.[4][11] However, another account states that the sister managed to escape, and ran away to modern-day Namibia.

The Dutch in Luanda sent Nzingha reinforcements, and with their help, Nzingha routed a Portuguese army in 1647.[2] Nzingha then laid siege to the Portuguese capital of Masangano. The Portuguese recaptured Luanda with a Brazilian-based assault led by Salvador Correia de Sá, and in 1648, Nzingha retreated to Matamba and continued to resist Portugal for the next 20 years.[6]

She implemented guerrilla warfare tactics and had begun to order trenches to be made around her island, created hidden caves, and stocked up on supplies to prepare her people for a potential long standing siege. She also made an unusual decree, establishing her kingdom as a safe haven for runaway slaves seeking refuge from the European colonists. In those thirty years fighting against the Portuguese, she created false alliances with neighboring kingdoms, expanding her reign farther and farther, even as she got older.[7]

Final years

In 1656, after meeting two Capuchin missionaries, she converted again to Christianity. This conversion was notable, as she had opposed Christianity since 1627, but she later tried to similarly convert her people.[14]

On November 24, 1657, the Portuguese decided to give up their claims to Ndongo and the land was returned to its traditional leader through a treaty ratified in Lisbon by King Pedro VI.[6] After the wars with Portugal ended, she attempted to rebuild her nation, which had been seriously damaged by years of conflict and over-farming. She developed Matamba as a trading power by capitalizing on its strategic position as the gateway to the Central African interior.[6] She was anxious that Njinga Mona's Imbangala would not succeed her as ruler of the combined kingdom of Ndongo and Matamba, and inserted language in the treaty that bound Portugal to assist her family to retain power. Lacking a son to succeed her, she tried to vest power in the Ngola Kanini family and arranged for her sister to marry João Guterres Ngola Kanini and to succeed her. This marriage, however, was not allowed, as priests maintained that João already had a wife in Ambaca.

She devoted her efforts to resettling former slaves and allowing women to bear children.[1] Despite numerous efforts to dethrone her, especially by Kasanje, whose Imbangala band settled to her south, and the many attempts by the Portuguese to kill her, Nzingha died a peaceful death at the age of eighty-two on December 17, 1663, in Matamba.[2]

Matamba went through a civil war in her absence, but Francisco Guterres Ngola Kanini eventually carried on the royal line in the kingdom. Nzingha's death accelerated the Portuguese occupation of the interior of South West Africa, fueled by the massive expansion of the Portuguese slave trade. Portugal would not have control of the interior until the 20th century. By 1671, Ndongo became part of Portuguese Angola.

In a peculiar legend, Nzingha was noted for executing her lovers. With a large all-male harem at her disposal, she had the men fight one another to the death in order to spend the night with her and, after a single night of lovemaking, were, in turn, put to death.[5]

Successors: Njinga's sister Barbara ruled briefly, until 1666 after she died, and then after the civil war that defeated Njinga Mona's claims, she had two male successors, Joao Guterres Ngola Kanini and his son Francisco.

Legacy

Today, she is remembered in Angola as the Mother of Angola, the fighter of negotiations, and the protector of her people. She is still honored throughout Africa as a remarkable leader and woman, for her political and diplomatic acumen, as well as her brilliant military tactics.[1] Accounts of her life are often romanticized, and she is considered a symbol of the fight against oppression.[15] Nzingha ultimately managed to shape her state into a form that tolerated her authority, though surely the fact that she survived all attacks on her and built up a strong base of loyal supporters helped as much as the relevance of the precedents she cited. While Njinga had obviously not overcome the idea that females could not rule in Ndongo during her lifetime, and had to 'become a male' to retain power, her female successors faced little problem in being accepted as rulers.[11] The clever use of her gender and her political understandings helped lay a foundation for future leaders of Ndongo today. In the period of 104 years that followed Njinga's death in 1663, queens ruled for at least eighty of them. Nzingha is a leadership role model for all generations of Angolan women. Women in Angola today display remarkable social independence and are found in the country’s army, police force, government, and public and private economic sectors.[11] Nzingha was embraced as a symbol of the People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola during civil war.[6]

A major street in Luanda is named after her, and a statue of her was placed in Kinaxixi on an impressive square in 2002,[1] dedicated by President Santos to celebrate the 27th anniversary of independence. Angolan women are often married near the statue, especially on Thursdays and Fridays.

The National Reserve Bank of Angola (BNA) issued a series of coins in tribute to Nzingha "in recognition of her role to defend self-determination and cultural identity of her people."[16]

An Angolan film, Njinga: Queen Of Angola (Portuguese: Njinga, Rainha de Angola), was released in 2013.[17]

"She was a fierce anticolonial warrior, a militant fighter, a woman holding power in a male-dominated society, and she laid the basis for successful Angolan resistance to Portuguese colonialism all the way into the twentieth century," writes Aurora Levins Morales while cautioning that "she was also an elite woman living off the labor of others, murdered her brother and his children, fought other African people on behalf of the Portuguese, and collaborated in the slave trade."[18]

See also

- List of Rulers of Matamba

- List of Ngolas of Ndongo

- List of women who led a revolt or rebellion

- Nzinga a Nkuwu

- Pungo Andongo

References

Citations

- Elliott, Mary; Hughes, Jazmine (August 19, 2019). "A Brief History of Slavery That You Didn't Learn in School". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 August 2019. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- Snethen, J (16 June 2009). "Queen Nzinga (1583-1663)". BlackPast. Archived from the original on 15 October 2019.

- "Queens of Infamy: Njinga". Longreads. 2019-10-03. Retrieved 2020-05-30.

- Miller, Joseph C (1975). "Nzinga of Matamba in a New Perspective". The Journal of African History. 16 (2): 201–216. doi:10.1017/S0021853700001122. JSTOR 180812.

- Jackson, Guida M. (1990). Women Who Ruled: A Biographical Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 130. ISBN 0874365600.

- Burness, Donald (1977). "Nzinga Mbandi' and Angolan Independence". Luso-Brazilian Review. 14 (2): 225–229. JSTOR 3513061.

- Williams, Hettie V. (2010). "Queen Nzinga (Njinga Mbande)". In Alexander, Leslie M.; Rucker, Walter C. (eds.). Encyclopedia of African American History. 1. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781851097746.

- Wallenfeldt, Jeff (2010). Africa to America: From the Middle Passage Through the 1930s. Britannica Educational Publishing. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-61530-175-1.

- Nzinga Mbandi, reine du Ndongo et du Matamba. UNESCO. 2014. p. 48. ISBN 978-92-3-200026-2.

- Stapleton, Timothy J. (2016). Encyclopedia of African Colonial Conflicts [2 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-59884-837-3.

- Masioni, Pat; et al. (2014). "Njinga Mbandi: Queen of Ndongo and Matamba". UNESCO Digital Library. Archived from the original on 2019-10-15.

- "Njinga Mbandi biography | Women". en.unesco.org. Retrieved 2020-05-31.

- Baur, John. "2000 Years of Christianity in Africa - An African Church History" (Nairobi, 2009), ISBN 9966-21-110-1, pp. 74

- Baur, John. "2000 Years of Christianity in Africa - An African Church History" (Nairobi, 2009), ISBN 9966-21-110-1, pp. 74-75

- Bleys, Rudi C. (1995). The Geography of Perversion: Male-to-Male Sexual Behavior Outside the West and the Ethnographic Imagination, 1750-1918. New York University Press. ISBN 9780814712658.

- "Angola to Launch New Kwanza Coins in 2015". Mena Report. 26 December 2014. Archived from the original on 11 September 2016. Retrieved 26 June 2016 – via HighBeam Research.

- "Njinga, Queen of Angola (Njinga, Rainha de Angola) UK Premiere". Royal African Society's Annual Film Festival. 6 November 2014. Archived from the original on 12 August 2016. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- Levins Morales, Aurora (2019). Medicine Stories: Essays for Radicals (Revised & Expanded Edition). Duke University Press. p. 79. ISBN 9781478003090.

Sources

Nzinga is one of Africa's best documented early-modern rulers. About a dozen of her own letters are known (all but one published in Brásio, Monumenta volumes 6-11 and 15 passim). In addition, her early years are well described in the correspondence of Portuguese governor Fernão de Sousa, who was in the colony from 1624 to 1631 (published by Heintze). Her later activities are documented by the Portuguese chronicler António de Oliveira de Cadornega, and by two Italian Capuchin priests, Giovanni Cavazzi da Montecuccolo and Antonio Gaeta da Napoli, who resided in her court from 1658 until her death (Cavazzi presided at her funeral). Cavazzi included a number of watercolours in his manuscript which include Njinga as a central figure, as well as himself. However, Cavazzi's account is peppered with a number of pejorative statements about Nzinga for which he does not offer factual evidence, such as her cannibalism.

- Brásio, António. Monumenta Missionaria Africana (1st series, 15 volumes, Lisbon: Agencia Geral do Ultramar, 1952–88)

- Baur, John. "2000 Years of Christianity in Africa - An African Church History" (Nairobi, 2009), ISBN 9966-21-110-1, pp. 74–75

- Burness, Donald. "'Nzinga Mbandi’ and Angolan Independence." Luso-Brazilian Review, vol. 14, no. 2, 1977, pp. 225–229. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3513061.

- Cadornega, António de Oliveira de. História geral das guerras angolanas (1680-81). mod. ed. José Matias Delgado and Manuel Alves da Cunha. 3 vols. (Lisbon, 1940–42) (reprinted 1972).

- Cavazzi, Giovanni Antonio da Montecuccolo. Istorica descrizione de tre regni Congo, Matamba ed Angola. (Bologna, 1687). French translation, Jean Baptiste Labat, Relation historique de l'Éthiopie. 5 vols. (Paris, 1732) [a free translation with additional materials added]. Modern Portuguese translation, Graziano Maria Saccardo da Leguzzano, ed. Francisco Leite de Faria, Descrição histórica dos tres reinos Congo, Matamba e Angola. 2 vols. (Lisbon, 1965).

- Gaeta da Napoli, Antonio. La Meravigliosa Conversione alla santa Fede di Christo delle Regina Singa...(Naples, 1668).

- Heintze, Beatrix. Fontes para a história de Angola no século XVII. (2 vols, Wiesbaden, 1985–88) Contains the correspondence of Fernão de Souza.

- Heywood, Linda. "Njinga of Angola: Africa's Warrior Queen." (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA. 2019).

- Miller, Joseph C. “Nzinga of Matamba in a New Perspective.” The Journal of African History, vol. 16, no. 2, 1975, pp. 201–216. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/180812.

- Njoku, Onwuka N. (1997). Mbundu. New York: The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. p. 4. ISBN 0823920046.

- Page, Willie F. (2001). Encyclopedia of African History and Culture: From Conquest to Colonization (1500-1850). 3. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 0816044724.

- Serbin, Sylvia; Rasoanaivo-Randriamamonjy, Ravaomalala (2015). African Women, Pan-Africanism and African Renaissance. Paris: UNESCO. ISBN 9789231001307.

- Snethen, J. (2009, June 16) Queen Nzinga (1583-1663). Retrieved from https://www.blackpast.org/global-african-history/queen-nzinga-1583-1663/

- Thornton, John K. (1991). "Legitimacy and Political Power: Queen Njinga, 1624-1663". The Journal of African History. 32 (1): 25–40. doi:10.1017/s0021853700025329. JSTOR 182577.

- Thornton, John K. (2011). "Firearms, Diplomacy, and Conquest in Angola: Cooperation and Alliance in West Central Africa, 1491-1671". In Lee, Wayne E. (ed.). Empires and Indigenes: Intercultural Alliance, Imperial Expansion and Warfare in the Early Modern World. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 9780814753095.

- Vansina, Jan (1963). "The Foundation of the Kingdom of Kasanje". The Journal of African History. 4 (3): 355–374. doi:10.1017/s0021853700004291. JSTOR 180028.

- Williams, Hettie V. (2010). "Queen Nzinga (Njinga Mbande)". In Alexander, Leslie M.; Rucker, Walter C. (eds.). Encyclopedia of African American History. 1. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781851097746.

Further reading

- Black Women in Antiquity, Ivan Van Sertima (ed.). Transaction Books, 1990

- Patricia McKissack, Nzingha: Warrior Queen of Matamba, Angola, Africa, 1595; The Royal Diaries Collection (2000)

- David Birmingham, Trade and Conquest in Angola (Oxford, 1966).

- Heywood, Linda and John K. Thornton, Central Africans, Atlantic Creoles, and the Making of the Americas, 1580-1660(Cambridge, 2007). This contains the most detailed account of her reign and times, based on a careful examination of all the relevant documentation.

- Heywood, Linda M. Njinga of Angola: Africa's Warrior Queen. Harvard University Press, 2017.

- Saccardo, Grazziano, Congo e Angola con la storia dell'antica missione dei cappuccini 3 Volumes, (Venice, 1982–83)

- Williams, Chancellor, Destruction of Black Civilization (WCP)

- van Sertima, Ivan, Black Women in Antiquity

- Nzinga, the Warrior Queen (a play written by Elizabeth Orchardson Mazrui and published by The Jomo Kenyatta Foundation, Nairobi, Kenya, 2006).

- The play is based on Nzinga and discusses issues of colonisation, traditional African rulership, women leadership versus male leadership, political succession, struggles between various Portuguese socio-political, and economic interest groups, struggles between the vested interests of the Jesuits and the Capuchins, etc.

- West Central Africa: Kongo, Ndongo (African Kingdoms of the Past), Kenny Mann. Dillon Press, 1996.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nzinga. |

- Bio-Comic strip at Wikimedia Commons, Pat Masioni et al.

- Article on Nzinga from Instituto Palmeiras

- Ana Nzinga: Queen of Ndongo at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Women Who Lead

- Maybe Nzinga is not so innocent