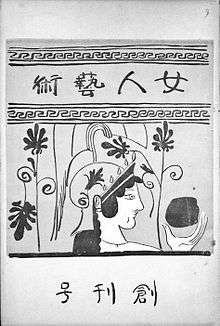

Nyonin Geijutsu

The Nyonin Geijutsu (女人芸術), which translates to Women's Arts, was a Japanese women's literary magazine that ran from July 1928 to June 1932. It was published by Hasegawa Shigure. They published 48 issues that focused on feminism and women's art and literature. It was one of the most influential Japanese literary women's magazines since the Seito.[1]

History

The Nyonin Geijutsu was first published in July 1928 by Hasegawa Shigure. The magazine was written, edited, designed, and published by women, and their goal was women's liberation. The magazine was funded by Hasegawa's husband, the popular author Mikami Otokichi.[2]

When the magazine first began publishing, Hasegawa was in charge of publication, Sogawa Kinuko was the editor, and the printer was Ikuta Hanayo. They published it in Hasegawa's home in what is now Shinjuku. Later Hasegawa also edited, and the place of publication moved to what is now Akasaka.[3]

The May and June 1930 issues were banned.[3] The October 1931 issue was banned. The magazine continued publication after the Mukden Incident, but suddenly stopped publishing in June 1932 because of Hasegawa's worsening health. The June issue was printed, but was destroyed. After that, the Nyonin Geijutsusha started a new magazine called Kagayaku.[4]

Notable contributors

Some writers for the magazine included Yaeko Nogami, Ichiko Kamichika, Yamakawa Kikue, Takamure Itsue, Yoshiko Yuasa, Miyamoto Yuriko, Fumiko Hayashi, Ineko Sata, Taiko Hirabayashi, Sasaki Fumiko Enchi, and Yoko Ota.[1] In the magazine's later years, male authors like Hajime Kawakami, Kiyoshi Miki, Eitaro Noro, and Takiji Kobayashi also contributed.[3]

At first they published serialized novels, poems, essays, and reviews, but eventually they began publishing more pleasure reading and proletarian fiction. However, it remained a fundamentally literary, left-leaning publication that reported on the Soviet Union, the labor movement, and international issues.[2] They also published articles by anarchists like Yuriko Mochizuki and Aki Yagi,[5] and communists like Yukiko Nakashima.[3]

Further reading

- Ogata, Akiko (1993). Nyonin-geijutsu-no-sekai Hasegawa Shigure to sono shūhen (2 satsu ed.). Tōkyō: Domesu Shuppan. ISBN 4810701174. OCLC 1106630001.

- Ogata, Akiko (1981). Nyonin Geijutsu no hitobito. Tokyo: Domesu Shuppan.

References

- Ericson, Joan E. (1997). Be a Woman: Hayashi Fumiko and Modern Japanese Women's Literature. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 9780824818845.

- Frederick, Sarah (2006). Turning Pages: Reading And Writing Women's Magazines in Interwar Japan. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 9780824829971.

- 高見順『昭和文学盛衰史』講談社 1965年

- Frederick, Sarah (2013). "Beyond Nyonin Geijutsu, beyond Japan: writings by women travellers in Kagayaku (1933–1941)". Japan Forum. 25 (3): 395–413. doi:10.1080/09555803.2013.804108. ISSN 0955-5803.

- Coutts, Angela (2013). "How do we write a revolution? Debating the masses and the vanguard in the literary reviews of Nyonin geijutsu". Japan Forum. 25 (3): 362–378. doi:10.1080/09555803.2013.804106. ISSN 0955-5803.