Novomessor albisetosus

Novomessor albisetosus, also known as the desert harvester ant, is a species of ant found in the United States and Mexico. A member of the genus Novomessor in the subfamily Myrmicinae, it was first described by Austrian entomologist Gustav Mayr in 1886. It was originally placed in the genus Aphaenogaster, but a recent phylogenetic study concluded that it is genetically distinct and should be separated. It is a medium-sized species, measuring 6 to 8.5 millimeters (0.2 to 0.3 in) and has a ferruginous body color. It can be distinguished from other Novomessor species by its shorter head and subparallel eyes.

| Novomessor albisetosus | |

|---|---|

| |

| N. albisetosus worker specimen | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | |

| Tribe: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | N. albisetosus |

| Binomial name | |

| Novomessor albisetosus Mayr, 1886 | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

N albisetosus is found in desert and woodland habitats, nesting underground or under stones. The ants are active during the morning and evening but not when it is midday or the middle of the night. They forage for foods such as insect pieces, plant tissues and fruit. They may forage individually but cooperate when transporting large food items. Army ants are known to prey on this species. Nuptial flights begin in June. Workers are considered matured when half of their time is spent outside.

Taxonomy

Novomessor albisetosus was originally identified by Austrian entomologist Gustav Mayr in 1886, who first described the species as Aphaenogaster albisetosa.[2] In 1895, Italian entomologist Carlo Emery classified Aphaenogaster as a subgenus of Stenamma, and N. albisetosus was renamed Stenamma (Aphaenogaster) albisetosum.[3] Emery would later transfer the species to the newly erected genus Novomessor, a genus he described in 1915 that included Novomessor cockerelli.[4] In 1947, American entomologist Jane Enzmann described a new form, Novomessor cockerelli minor. She distinguished it from N. cockerelli by its smaller size, lighter color and more sculptured body shape.[5] This taxon, however, was synonymized with N. albisetosus two years later by American entomologist William Brown Jr.[6]

In 1974, Brown synonymized Novomessor with Aphaenogaster, and N. albisetosus was thereby moved to that genus. Brown notes that the characters supposed to distinguish the two genera are not strong enough when one considers the global fauna of this complex.[7] However, entomologists Bert Hölldobler, R. Stanton and M.S. Engel revived the genus in 1976 on the basis that N. albisetosus and N. cockerelli had an exocrine gastral glandular system that was not found in any examined Aphaenogaster ant.[8] In 1982, English myrmecologist Barry Bolton argued that basing the genus on such a feature could not justify the separation of Novomessor and Aphaenogaster.[9] In 2015, a phylogenetic study done by entomologists B.B. Demarco and A.I. Cognato concluded that Novomessor was genetically distinct from Aphaenogaster, and the genus was revived from synonymy with N. albisetosus as one of the three known species. Morphologically, the promesonatal suture and the postpetiole are diagnostic for Novomessor ants and the three species share a closer relation with Veromessor than Aphaenogaster. They also have different behaviorial and habitat characters that distinguishes them from other ant genera.[10] Like N. cockerelli, N. albisetosus is commonly known as the desert harvester ant.[11]

Description

N. albisetosus is a medium-sized species with a moderately short body, measuring 6 to 8.5 millimeters (0.2 to 0.3 in).[2][12] The body color of the ant is ferruginous (rust-colored), the legs are reddish brown and the petiole (the waist) and abdomen are brownish black. The first segment of the abdomen, however, is brownish yellow. The tibia has fine, clear bristles. The maxillae form a triangular isoscele, and the mandibles have three comparatively large teeth. The head is noticeably long, longer than its total width. The clypeus (a sclerite) is also longer than wide and is found in the middle of the head, forming two vertical stripes.[2]

Larvae of N. albisetosus measure 6.6 millimeters (0.3 in). The body is moderately stout and there is a slight constriction at the first and second abdominal somites (body segments containing the same internal structures). Spiracles are small and no spinules are on the integument. Body hairs are short and sparse; hairs on the head are sparse and also short. The antennae are small with three sensilla (sensory receptors), and the labrum (a flap-like structure that lies immediately in front of the mouth) is short. The mandibles are sclerotized, and the apex forms a long slender tooth that is medially curved. The maxillae are small with a spinulose apex. Larvae appear similar to those of N. ensifer, but N. ensifer larvae can be distinguished by the abundance of hair with long stouts found on the body.[13]

Several features allow N. albisetosus to be distinguished from other species in Novomessor. One such feature is that the head of N. albisetosus is shorter than that of N. cockerelli. The sides of the head in front of the eyes are also subparallel, but behind the eyes they become convex. N. albisetosus has spines that are more bent and curve downward, whereas the spines of N. cockerelli are bent inward. Both species share a similarly structured thorax, but the epinotal spines in N. albisetosus are just as long as the basal face of the epinotum (the dorsal aspect of the pronotum). Meanwhile, N. cockerelli has shorter epinotal spines. N. albisetosus has a heavier structure and a greater degree of opacity; its petiole is almost opaque. It is hairier than N. albisetosus, where the body is covered in coarse whitish-yellow hairs. The hairs taper from the base to the tip, but they appear blunt. The abdomen bears numerous hairs that are shorter than the hair found on the pronotum (a sclerite of the prothorax). The queens can be distinguished from each other by the cephalic structure, where the head of N. albisetosus is slightly longer than it is broad, whereas the heads of N. cockerelli are decidedly longer than broad. Also, the thorax of N. albisetosus is shorter and higher than in N. cockerelli. Differences in their sculptures and pilosity are less noticeable, but N. cockerelli has a shinier epinotum and the head is rugose. Males of N. cockerelli are smaller, measuring 6 millimeters (0.2 in) and have short heads, and the mesonotum is covered with weak rugosities.[12]

Distribution and habitat

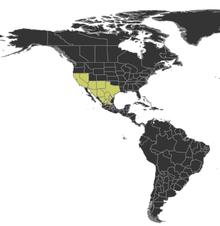

N. albisetosus is native to Mexico and the southwestern United States, including the U.S. states of Texas, New Mexico and Arizona. In Mexico, the ant is found in the states of Chihuahua, Durango and Sonora. The ant is less common than N. cockerelli.[14][15][16][17] The eastern range of N. albisetosus is not well known, but it does not coincide with N. cockerelli. The eastern-most record of N. albisetosus is near the Cernas Ranch in the Chisos Mountains of Texas. The mountains are close to northern Coahuila, so the ant is likely found in the Mexican ranges. In comparison to N. cockerelli, N. albisetosus is not found as far north and is found much further south. Both ants are found on the eastern side of the Sierra Madre Occidental until the topography changes in northwestern Chihuahua. Up north, the Sierra Madre Occidental breaks up into a number of ranges that communicate on the east of the Mexican Plateau, and, to the west, with the narrow Sonoran coastal plain where N. albisetosus and N. cockerelli are abundant. However, N. albisetosus is less widespread than N. cockerelli. The northern limit is mostly determined by its inability to survive in highland areas in central Arizona and New Mexico. In southeastern Wickenburg, Arizona, the range of N. albisetosus runs along the southern end of the area where the rise of the Mogollon Mesa begins; N. albisetosus is not found on top of the Mogollon Mesa.[17] Nests are found at altitudes of between 2,146 and 5,840 ft (654 and 1,780 m) above sea level.[18]

The habitat of N. albisetosus ranges from desert to juniper woodland, as well as pine-oak woodland and riparian woodland/desert scrub. Nests are underground or beneath stones.[18] Nests are noted for their coarseness; they typically have an irregular entrance 3 to 4 in (7.6 to 10.2 cm) across. These entrances are roughly constructed and descend steeply into the ground, appearing more like a rat's burrow than an ant's nest. Workers construct a disc around the central opening made out of coarse gravel and excavated soil. The discs in N. albisetosus colonies are smaller than those in N. cockerelli, but sometimes they may be absent (nests that are found under stones mostly lack discs). The center of the disc contains a thick pile of soil and gravel that has been formed into a rough crater.[12]

Behavior and ecology

N. albisetosus is active during the day and night, but does not forage in the middle of the night nor in the middle of the day when it is too hot.[10][19] It is most active when air temperatures are between 68 °F (20 °C) and 104 °F (40 °C). Water is a limiting factor to their foraging periods; these periods were extended when ants were given supplements of seeds, suggesting that physical stress can affect activity patterns.[20] When foragers do not form in files, they walk slowly and deliberately; it is doubted that they can move fast. Despite being previously known as individual foragers, N. albisetosus will recruit others when handling large prey items to carry them back to the nest in a cooperative manner. N. albisetosus can follow ant trails made by N. cockerelli, whereas the latter is unable to follow N. albisetosus trails.[21]

The ants consume a variety of foods, including insect pieces, seeds, plant tissues and pieces of fruit. However, they do not show a particular preference for seeds, and insect pieces only accounted for 6% of items collected by N. albisetosus.[12][19] Insect pieces collected by workers are most likely from already deceased insects since the slowness of these ants would make successful predation difficult.[12] Workers stridulate (produce sound by rubbing together certain body parts) when pieces of food they have found are too large to carry back. These stridulations can only be perceived by other workers who are either a short distance from the source or in direct contact.[22] The ants are aggressive to intruders, especially non-resident N. albisetosus ants and N. cockerelli; Pogonomyrmex badius were completely eliminated whenever introduced to an N. albisetosus nest area.[23] Army ants (Neivamyrmex) prey on N. albisetosus.[24]

Nuptial flights for N. albisetosus begin by June.[25] Adult workers are considered mature when they spend more than half of their time outside rather than remaining inside the nest tending to the young. These matured adults (excluding the oldest ones) will revert to tending the brood and queen when almost all age groups are removed from the nest.[26] In queens, the period of developing ovaries correlates with the age when worker ants are already present with the queen and brood. When workers no longer tend to the brood and queen, resorption of the ovaries occurs.[27]

See also

- Wildlife of the United States

References

- Johnson, N.F. (December 19, 2007). "Novomessor albisetosus Mayr". Hymenoptera Name Server version 1.5. Columbus, Ohio, USA: Ohio State University. Retrieved December 24, 2015.

- Mayr, G. (1886). "Die Formiciden der Vereinigten Staaten von Nordamerika" (PDF). Verhandlungen der Zoologisch-Botanischen Gesellschaft in Wien. 36: 419–464. doi:10.5281/zenodo.25865.

- Emery, C. (1895). "Beiträge zur Kenntniss der nordamerikanischen Ameisenfauna. (Schluss.)" (PDF). Zoologische Jahrbücher, Abteilung für Systematik, Geographie und Biologie der Tiere. 8: 257–360. doi:10.5281/zenodo.25455.

- Emery, C. (1915). "Definizione del genere Aphaenogaster e partizione di esso in sottogeneri. Parapheidole e Novomessor nn. gg" (PDF). Rendiconto delle Sessioni della R. Accademia delle Scienze dell'Istituto di Bologna. 19: 67–75. doi:10.5281/ZENODO.11435. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-11-18.

- Enzmann, J. (1947). "New forms of Aphaenogaster and Novomessor". Journal of the New York Entomological Society. 55: 147–153. doi:10.5281/zenodo.26332.

- Brown, W.L. Jr. (1949). "Synonymic and other notes on Formicidae (Hymenoptera)" (PDF). Psyche: A Journal of Entomology. 56 (1): 41–49. doi:10.1155/1949/54570.

- Brown, W.L. Jr. (1974). "Novomessor manni a synonym of Aphaenogaster ensifera (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)" (PDF). Entomological News. 85: 45–47.

- Hölldobler, B.; Stanton, R.; Engel, H. (1976). "A New Exocrine Gland in Novomessor (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) and its Possible Significance as a Taxonomic Character". Psyche: A Journal of Entomology. 83 (1): 32–41. doi:10.1155/1976/28626.

- Bolton, B. (1982). "Afrotropical species of the myrmicine ant genera Cardiocondyla, Leptothorax, Melissotarsus, Messor and Cataulacus (Formicidae)" (PDF). Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History). 45 (4): 307–370.

- Demarco, B.B.; Cognato, A.I. (2015). "Phylogenetic Analysis of Aphaenogaster Supports the Resurrection of Novomessor (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)". Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 108 (2): 201–210. doi:10.1093/aesa/sau013.

- Hölldobler, B.; Wilson, E.O. (1990). The Ants. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 239. ISBN 978-0-674-04075-5.

- Wheeler, W.M.; Creighton, W.S. (1934). "A study of the ant genera Novomessor and Veromessor" (PDF). Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. 69 (9): 341–388. doi:10.2307/20023057. JSTOR 20023057.

- Wheeler, G.C.; Wheeler, J. (1960). "Supplementary studies on the larvae of the Myrmicinae (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)" (PDF). Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington. 62 (1): 1–32. doi:10.5281/zenodo.26810.

- Smith, M.R. (1947). "A generic and subgeneric synopsis of the United States ants, based on the workers (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)". American Midland Naturalist. 37 (3): 521–647. doi:10.2307/2421469. JSTOR 2421469.

- Smith, D.R. (1979). Superfamily Formicoidea In: Krombein, Hurd, Smith & Burks. Catalog of Hymenoptera in America north of Mexico. Volume 2. Apocrita (Aculeata) (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press. p. 1360. ASIN B00KYGIGPG. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2016-02-26.

- Mackay, W.; Mackay, E. (2002). The Ants of New Mexico: (Hymenoptera:Formicidae). Lewiston, N.Y.: Edwin Mellen Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-7734-6884-9.

- Creighton, W.S. (1955). "Studies on the distribution of the genus Novomessor (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)". Psyche: A Journal of Entomology. 62 (3): 89–97. doi:10.1155/1955/67074.

- "Species: Novomessor albisetosus". AntWeb. The California Academy of Sciences. Retrieved December 8, 2017.

- Whitford, W.G.; Depree, E.; Johnson, P. (1980). "Foraging ecology of two chihuahuan desert ant species: Novomessor cockerelli and Novomessor albisetosus". Insectes Sociaux. 27 (2): 148–156. doi:10.1007/BF02229250.

- Young, A.M. (2012). Population Biology of Tropical Insects. Milwaukee, WI: Springer Science & Business Media. p. 83. ISBN 978-1-4684-1113-3.

- Hölldobler, B.; Oldham, N.J.; Morgan, E.D.; König, W.A. (1995). "Recruitment pheromones in the ants Aphaenogaster albisetosus and A. cockerelli (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)". Journal of Insect Physiology. 41 (9): 739–744. doi:10.1016/0022-1910(95)00041-R.

- Markl, H.; Hölldobler, B. (1978). "Recruitment and food-retrieving behavior in Novomessor (Formicidae, Hymenoptera). II. Vibration signals". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 4 (2): 183–216. doi:10.1007/BF00354979.

- Goldstein, M. H.; Topoff, H. (1985). "Reaction of the ant Novomessor albisetosus Mayr to intruders in the nest area (Hymenoptera: Formicidæ)". Insectes Sociaux. 32 (2): 173–185. doi:10.1007/BF02224231.

- McDonald, P.; Topoff, H. (1986). "The development of defensive behavior against predation by army ants". Developmental Psychobiology. 19 (4): 351–367. doi:10.1002/dev.420190408. PMID 3732626.

- Kannowski, P.B. (1954). "Notes on the ant Novomessor manni Wheeler and Creighton" (PDF). Occasional Papers of the Museum of Zoology. 556: 1–6.

- McDonald, P.; Topoff, H. (1985). "Social regulation of behavioral development in the ant, Novomessor albisetosus (Mayr)". Journal of Comparative Psychology. 99 (1): 3–14. doi:10.1037/0735-7036.99.1.3.

- McDonald, P.; Topoff, H. (1988). "Biological correlates of behavioral development in the ant, Novomessor albisetosus (Mayr)". Behavioral Neuroscience. 102 (6): 986–991. doi:10.1037/h0090427. PMID 3214545.

External links