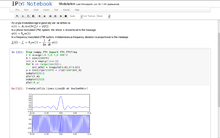

Notebook interface

A notebook interface (also called a computational notebook) is a virtual notebook environment used for literate programming.[1] It pairs the functionality of word processing software with both the shell and kernel of that notebook's programming language. Millions of people use notebooks interfaces[2] to analyze data for science, journalism, and education.

History

The notebook interface was first introduced in 1988 with the release of Wolfram Mathematica 1.0 on the Macintosh.[3][4][5] It was followed by Maple in 1989 when their first notebook-style graphical user interface was released with version 4.3 for the Macintosh.[6] As the notebook interface increased in popularity over the next two decades, kernels/backends to notebooks for many languages were introduced, including MATLAB, Python, Julia, Scala, SQL, and others.[7][8]

Use

Notebooks are traditionally used in the sciences as electronic lab notebooks to document research procedures, data, calculations, and findings. Notebooks track methodology to make it easier to reproduce results and calculations with different data sets.[7][8] In education, the notebook interface provides a digital learning environment, particularly for the teaching of computational thinking.[9][10] Their utility for combining text with code makes them unique in the realm of education. Digital notebooks are sometimes used for presentations as an alternative to PowerPoint and other presentation software, as they allow for the execution of code inside the notebook environment.[11][12] Due to their ability to display data visually and retrieve data from different sources by modifying code, notebooks are also entering the realm of business intelligence software.[7][13][14][15]

Notable examples

Example of projects or products of notebooks:

Free/open-source notebooks

- Apache Zeppelin — Apache License 2.0[16]

- Apache Spark Notebook[17] — Apache License 2.0

- IPython — BSD

- Jupyter Notebook (formerly IPython) — Modified BSD License (shared copyright model)[18]

- JupyterLab — Revised BSD License[19]

- Mozilla Iodide — MPL 2.0; development in alpha stage[20]

- R Markdown[21] — GPLv3[22]

- SageMath — GPLv3

- Org-mode on emacs (with the built-in babel addon) — GPL

- Xamarin Workbooksfor DotNet — MIT

Partial copyleft

- SMath Studio — Freeware, not libre: licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivatives

Proprietary notebooks

Early titles

- Wolfram Mathematica notebook

Later titles

References

- Standage, Daniel (2015-03-13). "Literate programming, RStudio, and IPython Notebook". BioWize. Wordpress. Retrieved 2016-12-01.

- Jupyter, Project. "JupyterLab is Ready for Users". Retrieved 30 May 2018.

- The ReDiscovered Future (2016-04-04), Macintosh + Mathematica = Infinity - April 1989, retrieved 2016-11-23

- Hayes, Brian (1990). "Thoughts on Mathematica" (PDF). PIXEL. January/February 1990: 28–35.

- "Launching Wolfram Player for iOS—Wolfram". Retrieved 2016-11-23.

- "MTN Special Issue 1994". web.mit.edu. Retrieved 2016-11-23.

- Osipov, Matt (2016-05-04). "The Rise of Data Science Notebooks". Datanami. Tabor Communications. Retrieved 2016-12-20.

- "The IPython notebook: a historical retrospective". blog.fperez.org. Retrieved 2016-11-23.

- Barr, Valerie; Stephenson, Chris (2011). "Bringing computational thinking to K-12: what is involved and what is the role of the computer science education community?".

- "How to Teach Computational Thinking—Stephen Wolfram". blog.stephenwolfram.com. Retrieved 2016-11-23.

- Databricks (2015-07-06), Spark Summit 2015 demo: Creating an end-to-end machine learning data pipeline with Databricks, retrieved 2016-11-23

- Frazier, Cat (2018-04-17). "Announcing Wolfram Presenter Tools". Retrieved 2018-11-27.

- Andrews, Ian (2016-03-30). "Delivering information in context". O'Reilly Media. Retrieved 2016-11-23.

- "jupyter-incubator/dashboards". GitHub. Retrieved 2016-11-23.

- Sharma, Shad. "Business Intelligence with Mathematica and CDF". Retrieved 2018-11-27.

- "Zeppelin". Apache. Retrieved 2018-12-20.

- "Spark Notebook". Archived from the original on 2018-10-01. Retrieved 2018-09-30.

- Jupyter Development Team (2015-04-22). "Licensing terms". Jupyter Notebook. GitHub. Retrieved 2018-12-20.

- Project Jupyter Contributors (2018-07-19). "LICENSE". JupyterLab. Retrieved 2018-12-20.

- "Iodide". Retrieved 2018-12-20.

- "R Markdown". R Studio. Retrieved 2018-09-30.

- "Licene". Readme. GitHub. 2018-12-07. Retrieved 2018-12-20.

- "Carbide Alpha | Buggy But Live!". Try Carbide. Retrieved 2018-12-20.

- "Databricks Unified Analytics Platform". San Francisco, CA: Databricks Inc. 2018. Retrieved 2018-12-20.

- "Datalore". JetBrains s.r.o. Retrieved 2019-08-08.

- "Nextjournal". nextjournal.com. Nextjournal GmbH. 2018. Retrieved 2018-12-20.

- "Observable". Observable HQ. Retrieved 2018-09-30.

- Observable (2018-12-15). "Repositories". San Francisco, California: Observable via GitHub. Retrieved 2018-09-30.

- "Terms of Service". Observable. 2018. Retrieved 2018-12-20.