Ysengrimus

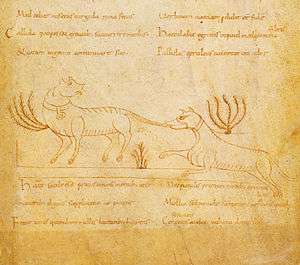

Ysengrimus is a Latin fabliau and mock epic, an anthropomorphic series of fables written in 1148 or 1149, possibly by the poet Nivardus. Its chief character is Isengrin the Wolf; the plot describes how the trickster figure Reynard the Fox overcomes Isengrin's various schemes.

The author

Little is known of the author. All that can be said of him with any certainty is that he lived in the twelfth century, and was closely connected to Ghent. The text is anonymous in the manuscripts containing the whole poem. Florilegia and medieval catalogues give the author's name variously as "Magister Nivardus", "Balduinus Cecus" (Baldwin the Blind), and "Bernard".[1]

The poem

The Ysengrimus draws on earlier traditions of beast fable in Latin, such as the eleventh century Ecbasis captivi; in the Ecbasis, the now traditional opposition of wolf and fox appears. The Ysengrimus is the most extensive anthropomorphic beast fable extant in Latin, and it marks the first appearance in Latin literature of the traditional names "Reinardus" and "Ysengrimus". The poem runs to 6,574 lines of elegiac couplets. The Ysengrimus is divided into seven books, which contain twelve or fourteen tales; opinions differ on how to divide them. Other beast fables were written by other medieval Latin authors, including Odo of Cheriton; the Ysengrimus is the most extensive collection of this material either in Latin or in any vernacular.

The poem mixes medieval and classical Latin imitations and parts of it are written in a curious, difficult style featuring obscure verb forms such as deponent imperatives. These stylistic curiosities reflect neither deliberate obscurantism nor lack of poetic talent: they are, instead, means of characterization. The poet places them on the lips of the trickster Reinardus, who is intended to be deceptive, and whose statements contain deliberate ambiguity. Ysengrimus is made to speak in a similar style when he is lying. But when he has been deceived into a predicament, he speaks plainly.

In the opening episode of Ysengrimus, the wolf manages to successfully deceive the fox by one of his schemes; this is Ysengrimus's only triumph, and throughout the remaining episodes Ysengrimus is constantly being tricked or humiliated by Reinardus. The poem contains the well known story in which Reinardus deceives Ysengrimus to go ice fishing using his tail as a net, only to get it frozen into the lake. When Reinardus mockingly urges Ysengrimus to get up quickly, Ysengrimus is made to say:

- Captus ad hec captor: "Nescis quid, perfide, dicas. Clunibus impendet Scotia tota meis."

- (The prisoner said this to his captor: "You don't know what you're saying, deceiver. I have all of Scotland hanging from my buttocks.")

Ysengrimus is usually held to be an allegory for the corrupt monks of the Roman Catholic Church. His greed is what typically causes him to be led astray. He is given to say that he will absolve the sins of the other characters.[2] He comes to a grisly end in the ending of the poem: stripped of his skin and thrown to the swine. Reinardus, by contrast, represents the poor and the lowly; he triumphs over Ysengrimus by his wits.

Nivardus deals with a subject that got extensive treatments in European popular culture during the Middle Ages and the early modern period. The characters Ysengrimus and Reinardus were clearly well developed by the time he wrote his epic; later treatments, however, usually featured Reynardus and relegated Ysengrimus the wolf to the menagerie of stock characters that served as Reynardus's supporting cast. They went on to appear in most Western European vernaculars, including French, Dutch, and English. A version of the Reynard stories was one of the first English printed books, made by William Caxton.

References

- Full discussion of authorship at Mann, 1987, 156-81.

- Nivardus.; Mann, Jill, trans. (1987). Ysengrimus. Leiden: Brill. p. 73. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- Voigt, Ernst, Ysengrimus (Halle, 1884)

- Mann, Jill, "Beast epic and fable"; in Medieval Latin, an Introduction and Bibliographical Guide, Frank A. C. Mantello and Arthur G. Rigg, editors. (Catholic University of America, 1996) ISBN 0-8132-0842-4

- Mann, Jill. Ysengrimus: Text with Translation, Commentary, and Introduction (Univ. Leiden, 1987) ISBN 90-04-08103-8

- Harrington, K.P., and Pucci, Joseph. Medieval Latin (2d. edition, Univ. Chicago, 1997) ISBN 0-226-31713-7

- J. M. Ziolkowski, Talking Animals: Medieval Latin Beast Poetry 750-1150, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1993.

External links

- Ernst Voigt's 1884 edition of Ysengrimus

- Jill Mann's 1987 translation of Ysengrimus

- A Wolf at School by Ayers Bagley

- The History of Reynard the Fox by Henry Morley, 1889.

- Comprehensive bibliography on Arlima (Archives de littérature du Moyen Âge)