Nina Koshetz

Nina Koshetz (Ukrainian: Ніна Павлівна Кошиць; Russian: Нина Павловна Кошиц; née Poray-Koshetz (uk:Порай-Кошиці); 30 December 1891 – 14 May 1965) was a Russian-Ukrainian, later American opera soprano, recital singer and actress. The niece of Oleksandr Koshytsa.

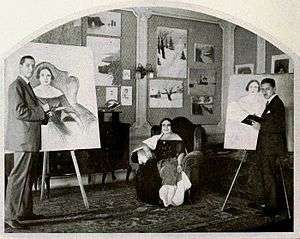

Nina Koshetz | |

|---|---|

Koshetz in The Chase, 1946 | |

| Born | December 30, 1891 |

| Died | May 12, 1965 (aged 73) |

Early life and career

Nina Koshetz was born in Kyiv, then moved to Moscow and became an opera singer. Her father, opera singer Pavel Koshetz (Ukrainian: Павло Олексійович Кошиць; ru: Павел Алексеевич Кошиц; 1863 - 2 March 1904), committed suicide in 1904, when Nina was 12 years old. From 1908–13 she studied in Moscow State Conservatory with Konstantin Igumnov and Sergei Taneyev, among others.[1]

Having received voice lessons in France from the retired dramatic soprano Felia Litvinne, she sang leading roles in opera and performed in principal opera houses across Russia and Europe. In the late 1910s she performed at the Petrograd Conservatory and was accompanied by then-unknown Vladimir Horowitz. She had initially resisted being accompanied by the unknown student, but afterward insisted only he could accompany her there; she subsequently programmed some of Horowitz's songs.

In 1920 Koshetz joined Ukrainian Republic Capella co-founded and led by her uncle Oleksandr Koshyts on their European Tour. After which she emigrated to the US and joined the Chicago Opera Association where she sang in the premiere of Prokofiev's The Love for Three Oranges (1921).

Nina Koshetz later performed for the Russian Opera Company in New York City and on tour in South America. At the end of the 1920s she was active in France, where she appeared in the French premiere of Sadko. Known for her overly-extravagant life style, her vocal powers declined in the 1930s and in 1940 she retired to Hollywood where she made a living as a voice teacher and restaurateur (a venture that ended in bankruptcy in 1942). She appeared in bit parts in several Hollywood movies. She died in Santa Ana, California in 1965.

Nina's daughter Marina Koshetz (also known as Marina Schubert; 1912–2001) was an operatic soprano.

Relationship with Rachmaninoff

She had a working relationship with composer Sergei Rachmaninoff during the 1910s, and he composed a cycle of six romantic songs dedicated to her (opus 38).[2]

Recordings

- The Nina Koshetz Edition - 1916-1941

Songs by Mussorgsky, Tchaikovsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, Gretchaninov, Varlamov, Rachmaninoff, Anton Arensky, Martini, Ponce, Ravel, and Chopin etc.; arias from Sadko, The Demon, Dobrynia Nikititch, The Fair at Sorochyntsi, Pique Dame and Prince Igor. CD released 1993 (Opal/Pavilion Records, 9855)

- Nina Koshetz – Complete Victor and Schirmer recordings 1928/29 and 1940 (and Odarka Trifonieva Sprishevskaya – Victor recordings)

Songs and arias by Borodin, Rimsky-Korsakov, Ravel, Ponce, Martini, Chopin, Gretchaninov, Rachmaninoff, Arensky, Tchaikovsky. (Nimbus Prima Voce CD NI 7935-36)

Film roles

She appeared as "Countess Vorontsov" opposite Ivan Mozzhukhin in the silent film The Loves of Casanova (1927), and as "Fatme" in Secrets of the Orient (1928). After her retirement from the operatic and concert stage, she appeared in bit parts in talkie films such as Algiers (1938), The Chase (1946), Captain Pirate (1952), and Hot Blood (1956).

Further reading

- Scott, M (1979), The Record of Singing II, pp 23–25

- Scott, M (2008), "Rachmaninoff" (The History Press. Gloucester, 2008.) pp 109–110; ISBN 978-0-75094-376-5

- Steane, J B (1992), 'Koshetz, Nina' in The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, ed. Stanley Sadie (London); ISBN 0-333-73432-7

References

- (in Russian)Aron Proujanski. Moscow. Native singer. 1750—1917: Dictionary—Pub. 2nd —М., 2008

- Scott. "Rachmaninoff" (see further reading)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nina Koshetz. |