Nils Ludvig Arppe

Nils Ludvig Arppe (19 December 1804 — 9 December 1861) was a Finnish industrialist.

Nils Ludvig Arppe | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 19 December 1803 |

| Died | 9 December 1861 (aged 57) Värtsilä, Grand Duchy of Finland |

| Monuments | bust in Kitee |

| Education | jurist |

| Occupation | industrialist |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children |

|

| Parent(s) | Nils Arppe and Margareta Sofia née Wegelius[1][2] |

Arppe studied jurisprudence but returned in his home area leading a sawmill together with his brother-in-law Johan Fabritius. Eventually he owned many sawmills and owned large forest areas. Due to economical regulation of forest resources, he started processing iron from local limonite resources.

In 1832, Arppe built the first steamship of Finland. He also made experiments with forestry and agricultural methods.

Arppe was married for three times and got altogether eleven children.

Arppe's business led to development of Wärtsilä company.

Early life and studies

Arppe's parents were lagman Nils Arppe and Margareta Sofia née Wegelius.[1][2] Nils Ludvig was second oldest from eight children, who lagman Nils Arppe got in his three marriages. The home language in the family was Swedish which he preferred to use in his letters. Also his Finnish was excellent, and when Arppe went to school in Savonlinna, the teaching language was German. He went to gymnasium in Turku[2] and graduated in 1820. Arppe followed his father's steps and studied law. He graduated in 1823 as jurist.[1] Arppe worked shortly as court of appeal trainee[1][2] in Vaasa,[2] but he left the lawyer career already in the same year.[1] The reason was unexpected death of his father; Arppe supposed that he could not earn enough as a lawyer to be able to take care of his siblings, and therefore he decided to return to North Karelia.[2]

Puhos sawmill

Arppe became business partner with his brother-in-law Johan Fabritius who had a sawmill in Puhos.[1] Fabritius was practically incapable to operate the sawmill, and therefore Arppe took care of the operations virtually alone.[2] Fabritius died in 1833, after which Arppe continued operating the sawmill.[1][2] After number of application, Arppe was finally allowed to saw 10,000 logs annually, which made the sawmill one of the largest in Finland. For several times Arppe applied for permission to convert the hydropowered sawmill steam powered, but this was denied, because there was a wide concern that the natural resource would run out.[2]

The sawmill employed 200–300 people at its best days. Arppe never owned the plant; after Fabritius's death it belonged to the widow Sofia, who was Arppe's sister, and her children.[2]

Kuurna sawmill

After gaining some experience, Arppe started building a sawmill to Kuurna, Pielisjoki in 1832. The Kuurna river had enough of capacity to power a large sawmill and it was wide enough for transportation. In addition, Arppe commissioned building a channel in Utra, to ease access from lake Pyhäselkä to downstream from Kuurna rapids. He bought forests in Ilomantsi for raw material. The scale of the sawmill caused fear among local neighbourhood and politicians for adequacy of wood resource in forests. As soon as the plant was commissioned the Senate ordered Arppe to close it down.[1]

Following the order of closing down the new sawmill, Arppe lost 10,000 hectares of land in court case against the state, due to different interpretation of ownership of wilderness. Arppe's main opponent in Senate in both cases was Lars Gabriel von Haartman.[1] Freiherr von Haartman had a lot of political power, and Arppe had no chance to overrule him.[2]

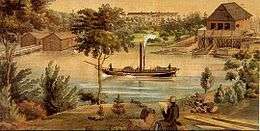

Steamship Ilmarinen

Timber produced in Puhos was transported by ship to Joutseno or Lappeenranta, south side of lake Saimaa, and after that by horse carriage to Uuras. The narrow and curvy passages at lake Saimaa made sailing difficult.[1] Therefore, in September 1832 Arppe applied from the Russian czar for a permission to build a steamship and to have a 50-year-long exclusive right for steamship traffic at lake Saimaa. The decision making was given to the Finnish Senate which granted him permission to build the ship, but limited the traffic privilege to 20 years. The ship was built by Ostrobothnian master builder Sandsund.[2] The engine was bought from Saint Petersburg,[1] but it was made in Clarke Engineering Works in England.[2] Paddle steamer Ilmarinen was the first Finnish-built steamship;[1][2] she made her maiden voyage from Puhos to Honkalahti in Joutseno in summer 1833. The captain was Taneli Rouvinen. Ilmarinen was used for tugging barges from Joensuu, Puhos and Varkaus to Joutseno.[1] The ship could tug 5–6 barges Arppe also rented the vessel for other sawmill operators, getting a good profit.[2] Ilmerinen served until 1844, when she was decommissioned, and Arppe handed over his steam traffic privilege to Kuopio Viikki brothers.[1] One reason for ending the steam traffic was that Arppe built a sort of "horse railway" over isthmus between Orivesi and Pyhäjärvi, which eased transportation so much that steam ship became unnecessary.[2]

Move to Koivikko

Arppe lived with his siblings in Puhos estate which consisted about 30 rooms. In about 1835 there moved Carl Gustaf von Essen as a home teacher for Sofia's children.[2] He brought a strict pietistic atmosphere with him, and Sofia fell in love with the young and fiery teacher, who she later married. Arppe, however, could not stand his pathos, and therefore moved apart from the family estate to northern side of lake Ätäsköjärvi in Koivikko where he built a house[1][2] in 1840, the same year when he married his first wife Jeannette.[2]

Agriculture and forestry

Arppe travelled to Central Europe in 1845 gaining knowledge about agriculture and forestry. He applied the ideas at his own property.[2] In order to get more land for fields, he reduced the mater level of lake Pyhäjärvi by opening Puhoksenkoski rapids. Consequently, water level went down by two metres and the other discharging river Hiiskoski almost dried out. Flow in Puhoskoski increased, while the height of fall got lower.[1] As a result, Arppe gained 200 hectares of land. Arppe tested new farming methods in his property. He bought cattle from Netherlands and founded a dairy.[2]

Arppe promoted afforestation in order to maintain availability of the natural resource. He planted a larch forest between Koivikko and Puhos.[1][2] The 1847 planted 12-ha forest included 3,000 saplings which were Siberian and European larch, and some local Scots pines and Norway spruces for reference.[2] The forest is the largest larch forest of Finland and it is nowadays natural reserve.[3]

Arppe suggested obligating slash-and-burn farmers to plant larches on old fields, but his idea was not supported.[1]

Iron processing

Arppe was annoyed because of closing down the new Kuurna sawmill.[1] Another cause of disappointment was sawmill act, promoted by Haartman, that came into force in 1851 setting limits to potential of the industry. When Sofia and her children wanted to sell the Puhos sawmill in 1856, Arppe was not interested in it any more; the plant was sold to Antti Mustonen and Simo Parviainen.[2]

Arppe had bought a sawmill in Värtsilä in 1836 with rights of processing 10,000 logs annually. The plant had been founded two years earlier, on 12 April 1834. After introduction of the sawmill act, the Finnish Senate wanted to encourage iron processing. Arppe was awarded a permission to build two furnaces in Värtsilä for limonite processing, four power hammers and a workshop. Arppe got a loan free of interest from the state and tax exemption for 15 years.[4] Arppe bought rights of using hydro power from Jukajoki sawmill. The raw material, limonite, was collected in Ilomantsi, Kiihtelysvaara and Tohmajärvi.[1]

He opened another ironworks in Ilajankoski, but the production volume remained small due to unfavourable connections.[1]

Another, more prominent plant was built by Möhkönkoski rapids; it was operated by Rauch brothers since 1848. The ironworks was close to Arppe's lands[1] and the owners had made mining claims in lakes which were inside Arppe's forests.[4] Arppe raised court cases claiming for example that the iron mill is polluting meadows from which the local people get food for their animals. After the Rauch brothers got enough of Arppe's disturbance and left, Arppe redeemed the ironworks to himself in 1851.[1] This happened before the Värtsilä plant was started.[4]

In Arppe's ownership the Möhkö became the largest limonite processor of Finland.[1] The main problem in both ironmills was the high phosphorus content in the mineral; this made the iron hard but fragile. In 1859, Arppe got licence to build a steam-powered puddling and rolling plant in Värtsilä; it was used for the production of both Värtsilä and Möhkö.[4]

The ready ingots were transported to Värtsilä or through Pälkjärvi to shore of lake Ladoga.[1] After the Saimaa Channel was taken into use in 1856, the products could be transported by water. The main market areas were Saint Petersburg and south side of Gulf of Finland. Crimean War increased the demand temporarily, but after that prices dropped. Although the Finnish iron ingots and bars were duty-free in the Russian market, the highly developed international iron producers could sell their products for a competitive price despite of tariffs. Arppe's other supporting leg was his timber industry which enabled investments on ironmills.[4]

Ingots were further processed into bars in Värtsilä. Arppe's company employed thousands of people; Möhkö works alone gave work to 2,000 men for limonite digging, coal burning, operating of barges and driving horses. Arppe's plants provided significant income to the local people. The plants attracted many workers from distant locations and the local food production could not cover the need. Arppe printed his own notes, called "dog tongues", which could be used as payment in company shop.[1]

Läskelä sawmill

In 1859, Arppe stepped back to forest industry by buying Läskelä hydropowered sawmill. As the sawmill was situated by river Jänisjoki which also flows through Värtsilä, the significance of Värtsilä grew as the main location of Arppe's company.[1]

Private life

Arppe was married to Jeannette Charlotta née Porthan in 1841, but she died already in 1843. In 1845, Arppe married her sister Matilds, who died ten years later. Arppe's third wife was Amalia Kristina née Seitz. He had altogether eleven children.[1]

Arppe remained faithful to his home county and he had a reputation as a man on whose word one can count.[2] While he was a hard industrialist, he had the ability to identify the capable people among uneducated peasants and put them to responsible positions; such were Taneli Rouvinen, Staffan Riikonen and Paul Hendunen, who worked as plant managers.[1]

Arppe had far-reaching plans for developing his business, but they did not materialise before[2] he fell seriously ill. Despite of being partly paralysed, he wanted to be in place seeing when the last pieces of machinery of his rolling plant, warped along river Jänisjoki, arrived in Värtsilä.[4] Arppe died in 1861, shortly before era of economical deregulation in Finland.[1][2]

Arppe left as inheritance a significant amount of land; according to estimates, it totalled 120,000–130,000 hectares. His business was continued after and led to development of Wärtsilä company.[4]

Sources

- Saloheimo, Veijo (2009-01-28). "Arppe, Nils Ludvig (1803–1861)". Kansallisbiografia (in Finnish). Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura. Retrieved 2016-01-15.

- "Puhoksen patruuna" (in Finnish). Kitee: Municipality of Kitee. Archived from the original on 2018-08-05. Retrieved 2016-01-15.

- Holm, Milla (2014-09-28). "Suomen suurin lehtikuusimetsä on Arppen vehmas monumentti" [Finland's largest larch forest is a verdant monument of Arppe] (in Finnish). Yle. Retrieved 2016-01-15.

- Haavikko, Paavo (1984). "1834–1907; subchapter 1". Wärtsilä 1834–1984 (in Finnish). Oy Wärtsilä Ab. pp. 7–8. ISBN 951-99542-0-1.