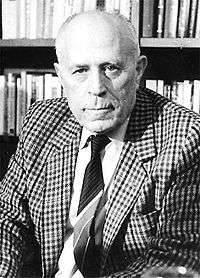

Nikolay Haytov

Nikolay Haytov (Bulgarian: Николай Хайтов), or Nikolai Haitov (15 September 1919 – 30 June 2002) was a Bulgarian fiction writer, playwright, patriot and publicist known for his publications and research regarding the life of Bulgarian revolutionary Vasil Levski.

Николай Хайтов Nikolay Haytov | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 15 September 1919 Village of Yavrovo, Plovdiv Province, Bulgaria |

| Died | 30 June 2002 (aged 82) Sofia, Bulgaria |

| Occupation | Writer, playwright, publicist and patriot |

| Nationality | Bulgarian |

Early life and education

Born to a poor family of ordinary peasants in the village of Yavrovo, in Kuklen municipality, Plovdiv Province, Haytov finished junior high school in his native village and then moved to Plovdiv, where, instead of studying, he worked as an apprentice in a flour shop, as a waiter in a pub, as a valet and in the railway. He finished high school in Asenovgrad in 1938, becoming attracted to the work of writers such as Zahari Stoyanov, Ivan Vazov, Elin Pelin and Yordan Yovkov. Haytov graduated from the Faculty of Forestry in Sofia in 1943.

He became a soldier in Plovdiv in the autumn of 1944 and then went on to work as a forest guard and forester in the Rhodope Mountains: in the Persenk forestry enterprise, in Lesichovo, in Sapareva Banya and in the Raduil section of the Borovets enterprise. Sentenced to eight years in prison for incorrect distribution of wood and dismissed by the Ministry of Forestry, his sentence was later repealed, but he nevertheless remained unemployed for two years.

Writing career

His first feature article was published in 1954 in the Septemvri magazine, and he continued to work with the magazine, which printed the story Sluchay bez pretsedent (Case With No Precedent) and another article. Haytov then wrote articles for Rabotnichesko Delo, Kooperativno selo and other newspapers. Some of these articles were published in his first book Sapernitsi (Rivals) in 1957. Haytov was accepted as a member of the Union of Bulgarian Writers (UBW) in 1959 and worked as an editor for the newspaper Narodna kultura and the magazine Nasha rodina. Between 1975 and 1977 he was the chairman of the Capital Council of Culture, a member of the executive council of UBW since 1966 and its secretary between 1966 and 1968. In 1966 he became editor-in-chief of Rodopi magazine.

In 1967, Haytov's famous book Divi razkazi (Wild Stories) was released. Since published in ten editions in Bulgaria and translated in 28 languages, including Chinese, it is regarded as one of the most successful modern Bulgarian literary works. The book is included in the UNESCO Historical Collection.[1]

Haytov's Izbrani proizvedeniya (Selected Works) was published in 1989 in three volumes. He has written over 10 stage plays, 800 articles and reviews. The total print of Haytov's books released in Bulgaria is over 4 million. He was also the screenplay writer for a number of films and TV series, including The Goat Horn (1972), Manly Times (1977), Captain Petko Voivode, Darvo bez koren, Orisiya, Semeystvo Kalinkovi, Lamyata.

Chairman of UBW between 1993 and 1999, Haytov is the winner of numerous awards and orders. He has two sons, Aleksandar and Zdravets, and a daughter, Elena. Haytov died of leukemia in 2002.

Works

- Sapernitsi (1957)

- Iskritsi ot ognishteto (1959)

- Razbudena Rodopa (1960)

- Pisma ot pushtinatsite (1960)

- Hayduti (1962)

- Starite u doma (1962)

- Zheni haydutki (1962)

- Matey Mitkaloto (1964)

- Shumki ot gabar (1965)

- Rumyana voyvoda 1965)

- Rodopski vlastelini (1965)

- Divi razkazi (1967)

- Magyosnikat ot Breze (1979)

- Hvarkatoto korito 1979)

- Rodopskite komiti razkazvat (1972)

- Kapitan Petko Voyvoda (1974)

- Razkazi i eseta 1984)

- Da vazsednesh gligan 1985)

- Bodlivata roza (1975)

- Valshebnoto ogledalo (1981)

- Poslednite migove i grobat na Vasil Levski (1985)

- Izbrani proizvedeniya (1989)

- Prez sito i resheto (2003, posthumously)

- Troyanskite kone v Balgariya (2002, posthumously)

- Dnevnitsi

References

External links

- Nikolay Haytov on Liternet.bg (in Bulgarian)

- Hristov, Ivaylo. Nikolay Haytov, monograph (in Bulgarian)