Nikolai Pomyalovsky

Nikolai Gerasimovich Pomyalovsky (Russian: Никола́й Гера́симович Помяло́вский), (23 April [O.S. 11 April] 1835 – 17 October [O.S. 5 October] 1863), was a Russian novelist and short story writer.

Nikolai Pomyalovsky | |

|---|---|

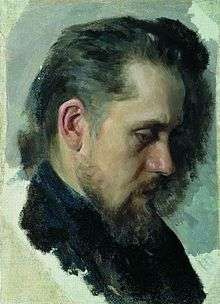

Pomyalovsky by Nevrev 1860 | |

| Born | April 23, 1835 Saint Petersburg, Russia |

| Died | October 17, 1863 (aged 28) Saint Petersburg, Russia |

| Period | 1850s-1860s |

| Genre | Fiction |

| Notable works | Seminary Sketches |

| Signature | |

Early life

Pomyalovsky was born in Saint Petersburg in 1835. His father was a deacon in the Orthodox Church in Malaya Okhta, a village on the bank of the Neva River, across from Saint Petersburg. Pomyalovsky studied at the Alexander Nevsky Theological School (1843–51), where his lifelong problem with alcoholism began, and at the Saint Petersburg Theological Academy (1851–1857).[1] His work Seminary Sketches is a harrowing description of his years in these schools.[2] Though a talented student, he graduated next to last in his class, and wasn't recommended for a deaconship.[3]

Career

Upon leaving the seminary, he earned a living by serving at funerals, singing in choirs, and giving private lessons. He also attended lectures at Saint Petersburg State University. His story Vukol: A Psychological Sketch was published in the Journal for Education in 1859. The story tells of the progress of an intelligent but awkward orphan boy under the abuse and mistreatment of guardians and educators before he finally finds a teacher whose fatherly love he can respond to.[3] In 1860 he started teaching at the largest of Saint Petersburg's Sunday schools, which were staffed by volunteers, and designed to educate the children of the working class. He had high expectations for the usefulness and influence of the Sunday schools, but when these expectations went unrealized he turned to drinking again.[1]

He published his first novel Bourgeois Happiness in Sovremennik (The Contemporary). He also became friends with the editor of Sovremennik, Nikolay Nekrasov, and with its guiding spirit Nikolai Chernyshevsky. As a result of this success, he attended many parties, and drank heavily, which eventually landed him in the hospital with delirium tremens. His novel Molotov (1861- also published in Sovremennik), the sequel to Bourgeois Happiness, secured his reputation, and brought him into the company of writers like Ivan Turgenev and Fyodor Dostoyevsky.[1] The two novels tell the story of a poor young intellectual's search for self-realization and his place in the world. The protagonist Molotov, an orphan raised by a university professor, doesn't feel that he belongs anywhere or to any particular social class. The gentry family whose children he tutors are alien to him, and he's not seen by them as an equal, even though he's a college graduate. Molotov won't become a civil servant because he feels it would take away his freedom. His girlfriend Nadya must break all ties with her family, who want her to marry a middle-aged general, in order to be with Molotov. In the end Nadya chooses to be with Molotov as they try to enjoy a simple "bourgeois" lifestyle.[3]

Last years

He had hoped to find solidarity and fellowship in the Saint Petersburg literary circles, but found only backbiting, petty ambitions, and what he saw as condescension from the established gentry writers. He rebelled by getting drunk often and acting in a way that alienated his friends and literary connections. At a dinner party held by Dostoyevsky, he ended up passed out drunk on the floor. He began disappearing for weeks at a time, living in the Saint Petersburg slums among prostitutes and criminals, and continuing to feed his addiction to alcohol. His binges usually led to his being jailed or hospitalized. During this time he worked on his Seminary Sketches, the first of which was published in Dostoyevsky's journal Vremya (Time).[1] Seminary Sketches gives a fictionalized but accurate account of the 14 years that Pomyalovsky spent in the seminaries. He tells of the drudgery and mindless rote learning that Russia's future spiritual leaders were subjected to. He goes on to describe teacher-student favoritism, suppression of independent thinking, and an endless repetition of brutal floggings. The seminary is ruled by the strong and brings out the worst in the students while killing the good in them. Dmitry Pisarev reviewed Seminary Sketches together with Dostoyevsky's novel The House of the Dead under the title Those Who Are Lost and Those Who Are About to be Lost, pointing out that Dostoyevsky's novel was more optimistic than Pomyalovsky's work.[3]

Pomyalovsky attempted suicide several times, and spent the winter of 1862-63 in the hospital. In 1863 he moved to the country with his brother and two student acquaintances in an effort to break with his habits and find sobriety. Another binge, brought on by misunderstandings that broke up his living arrangement, nearly killed him. A few days into his recovery he noticed a sore on his leg. When doctors opened the sore, they found gangrene, which he soon died from.[1] After Seminary Sketches, Pomyalovsky had begun work on a major novel, Brother and Sister, dealing with lower class Saint Petersburg life, but it went unfinished. What he was able to complete of Brother and Sister shows his growth as a novelist.[3]

Pomyalovsky had a considerable influence on Maxim Gorky and others, and is ranked high among Russian realist writers.[1]

Bibliography

- Очерки бурсы: Seminary Sketches, Cornell University Press, New York, 1973. ISBN 0-8014-0765-6

- Мещанское счастье: Bourgeois Happiness

- Молотов: Molotov

- Брат и сестра: Brother and Sister (unfinished)

- Поречане: People from Porechye (unfinished)

Further reading

- "Pomyalovsky", an article from the Encyclopedia of Literature, Moscow (1929—1939) (in Russian)

References

- Kuhn, Alfred R. (1973). Introduction to Seminary Sketches. Cornell University Press. pp. xi–xxxvii. ISBN 0-8014-0765-6.

- The Cambridge History of Russian Literature. Cambridge University Press. 1992. p. 277. ISBN 0-521-42567-0.

- Terras, Victor (1991). A History of Russian Literature. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 335–336. ISBN 0-300-05934-5.