Nicholas Brigham

Nicholas Brigham (died 1558), is mentioned by Bale (Scriptores edit. 1557–9, not in that of 1548) as a Latin scholar and antiquarian, who gave up literature to practise in the law courts, and who flourished in 1550. To this Pits adds that he was no common poet and a good orator, and that in 1555 he built a tomb for the bones of Geoffrey Chaucer in Westminster Abbey. Later writers have taken this to be Nicholas Brigham, a "teller" of the exchequer, who died in 1558.[1]

Life

Anthony Wood (Athenæ Oxon. i. 309) conjectures that he was born near Caversham, where his eldest brother Thomas had lands of inheritance, and died in 6 Edward VI, but was descended from the Brighams of Brigham in Yorkshire. Now one Anthony Brigham was made bailiff of the king's manor of Caversham in 1543 (Pat. 35 Hen. VIII, p. 14, m. 6), and in 1544 had a grant of lands called Canon End there (Pat. 36 Hen. VIII, p. 2), but no Nicholas appears in the pedigree of Brigham of Canon End (Harl. MS. 1480, fol. 44, in which Anthony Brigham is erroneously called cofferer of the household), nor is either Anthony or Nicholas named in that of Brigham of Brigham (Poulson, Holderness, ii. 268). Wood further supposes that he studied at Hart Hall, Oxford, but whether or not he took a degree does not appear.[1]

Brigham became a teller of the Exchequer in 1545, and was promoted to first teller in 1555.[2] In the spring of 1558 the queen appointed him receiver of the loan made her by the City of London, and general receiver of all subsidies, fifteenths, or other benevolences.

Part of Sir Henry Dudley's conspiracy, for which many suffered death in 1556, was to seize the money of the exchequer in custody of Brigham. One of the conspirators, William Hunnys, or Hinnes, or Ennys, of the royal chapel, who "kept Brigham's wife, and was very familiar with him by that means", was to find a way to do this; but Brigham's own money, which he kept with the queen's, was not to be taken, as he was "a very plain man", and they would have enough money without his. Following Brigham's death in 1558, his widow married Hunnys, who had escaped the fate of most of his fellow-conspirators ; and there is in Somerset House an entry of a decree of 4 November 1559 that a will made some time between September and December 1558, leaving all his property to his wife, which will was disputed by James Brigham, nephew of Nicholas, is to be held valid, and that William Hunnys, "husband and executor of the last will and testament" of Margaret, late wife of Nicholas Brigham, is to execute the trusts contained in it. From this it appears that Brigham died in December 1558, and that Margaret did not long survive him – her will, dated 2 June 1559, was proved on 12 October following.

Brigham had one child, Rachael, who died on 21 June 1557, and was buried near Chaucer's tomb in Westminster Abbey with this inscription – Unica quæ fueram proles spesque alma parent um Hoc Rachael Brigham condita sum tumulo. Vixit annis quatuor, mensibus tribus, diebus quatuor horis 15.

Brigham wrote De Venationibus Rerum Memorabilium; Memoirs by way of a Diary and Miscellaneous Poems but none of these seem now to be extant.[1]

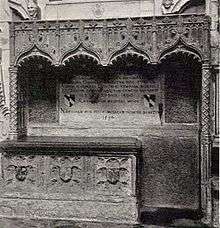

Chaucer's tomb

Perhaps his only literary production now known is his epitaph on Chaucer. Before his time a leaden plate hung in St. Bennet's Chapel, in Westminster Abbey, with Chaucer's epitaph by Surigonius of Milan (Dart, i. p. 83): Galfridus Chaucer vates et fama Poesis Materne hac sacra sum tumulatus humo. In 1555, Brigham removed the poet's bones to a marble tomb he had built in the south transept, and on which there was a portrait of Chaucer taken from Thomas Hoccleve De Regimine Principis, with this epitaph:

Qui fuit Anglorum vates ter maximus olim

Galfridus Chaucer conditur hoc tumulo:

Annum si quaeras Domini, si tempora vitse,

Ecco notae subsunt quse tibi cuncta notant.

Octobris 1400.

Ærumnarum requies mors.

After which comes:

N. Brigham hos fecit Musarum nomine sumptus.

and round the base:

Si rogitas quis eram, forsan te fama docebit;

Quod si fama negat, mundi quia gloria transit,

Haec monumenta lege.

References

-

- Perkins, Nicholas (2001). Hoccleve's Regiment of Princes. Boydell & Brewer. p. 175. ISBN 978-0-85991-631-8. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

![]()