Neural control of limb stiffness

As humans move through their environment, they must change the stiffness of their joints in order to effectively interact with their surroundings. Stiffness is the degree to a which an object resists deformation when subjected to a known force. This idea is also referred to as impedance, however, sometimes the idea of deformation under a given load is discussed under the term "compliance" which is the opposite of stiffness (defined as the amount an object deforms under a certain known load). In order to effectively interact with their environment, humans must adjust the stiffness of their limbs. This is accomplished via the co-contraction of antagonistic muscle groups.[1][2]

Humans use neural control along with the mechanical constraints of the body to adjust this stiffness as the body performs various tasks. It has been shown that humans change the stiffness of their limbs as they perform tasks such as hopping,[3] performing accurate reaching tasks,[4] or running on different surfaces.[5]

While the exact method by which this neural-modulation of limb stiffness occurs is unknown, many different hypotheses have been proposed. A thorough understanding of how and why the brain controls limb stiffness could lead to improvements in many robotic technologies that attempt to mimic human movement.[2]

Stiffness

Stiffness is typically viewed as a material property describing the amount a material deforms under a given force as described by Hooke's law. This means that objects with higher stiffness are more difficult to bend or deform than objects with lower stiffnesses. This concept can be extended to the limbs and joints of biological organisms in which stiffness describes the degree to which a limb or joint deflects (or bends) under a given load. Limb stiffness can also be described as the static component of impedance.[1][6] Humans change the stiffness of their limbs and joints to adapt to their environment.[5] Limb and joint stiffness has been previously studied and can be quantified in various ways. The basic principle for calculating stiffness is dividing the deformation of a limb by the force applied to the limb, however, there are multiple methods of quantifying limb and joint stiffness with various pros and cons. When quantifying limb stiffness, one cannot simply sum the individual joint stiffnesses due to the nonlinearities of the multi-joint system.

A few of the specific methods for calculating limb stiffness can be seen below:[7]

Vertical Stiffness (k vert) is a quantitative measure of leg stiffness that can be defined by the equations below:[7]

Where F max is the maximum vertical force and delta y is the maximum vertical displacement of the center of mass

Where m is the body mass and P is the period of vertical vibration

Where m is the mass of the body mass and ω 0 is the natural frequency of oscillation

Limb Stiffness (K_limb) is the stiffness of the entire limb and can be defined by the equations below:

Where F max is the maximum applied force and ΔL is the change in length of the limb

Torsional Stiffness (K_joint)is the rotational stiffness of the joint and can be defined by the equations below:

Where ΔM is the change in joint moment and Δθ is the change in joint angle

Where W is the negative mechanical work at the joint and Δθ is the change in joint angle

These different mathematical definitions of limb stiffness help to describe limb stiffness and show the methods by which such a limb characteristic can be quantified.

Stiffness modulation

The human body is able to modulate its limb stiffnesses through various mechanisms with the goal of more effectively interacting with its environment. The body varies the stiffness of its limbs by three primary mechanisms: muscle cocontraction,[1][8][9] posture selection,[6] and through stretch reflexes.[1][10][11][12]

Muscle cocontraction (similar to muscle tone) is able to vary the stiffness of a joint by the action of antagonistic muscles acting on the joint. The stronger the forces of the antagonistic muscles on the joint are, the stiffer the joint becomes.[2][8] The selection of body posture also affects the stiffness of the limb. By adjusting the orientation of the limb, the inherent stiffness of the limb can be manipulated.[6] Additionally, the stretch reflexes within a limb can affect the stiffness of the limb, however these commands are not sent from the brain.[10][11]

Locomotion and hopping

As humans walk or run across different surfaces, they adjust the stiffness of their limbs to maintain similar locomotor mechanics independent of the surface. As the stiffness of a surface changes, humans adapt by changing their limb stiffness. This stiffness modulation allows for running and walking with similar mechanics regardless of the surface, therefore allowing humans to better interact and adapt with their environment.[3][5] The modulation of stiffness therefore, has applications in the areas of motor control and other areas pertaining to the neural control of movement.

Studies also show that the variation of limb stiffness is important when hopping, and that different people may control this stiffness variation in different ways. One study showed that adults had more feedforward neural control, muscle reflexes, and higher relative leg stiffness than their juvenile counterparts when performing a hopping task. This indicates that the control of stiffness may vary from person to person.[3]

Movement accuracy

The nervous system also controls limb stiffness to modulate the degree of accuracy that is required for a given task. For example, the accuracy required to grab a cup off of a table i very different from that of a surgeon performing a precise task with a scalpel. To accomplish these tasks with varying degrees of required accuracy, the nervous system adjusts limb stiffness.[4][6] To accomplish very accurate tasks higher stiffness is required, however, when performing tasks where accuracy is not as imperative, lower limb stiffness is needed.[4][6] In the case of accurate movements, the central nervous system is able to precisely control limb stiffness to limit movement variability. The cerebellum also plays a large role in controlling for the accuracy of movements.[13]

This is an important concept for everyday tasks such as tool use.[6][14] For example, when using a screwdriver, if limb stiffness is too low, the user will not have enough control over the screwdriver to drive a screw. Because of this, the central nervous system increases limb stiffness to allow the user to accurately maneuver the tool and perform a task.

Neural control

The exact mechanism for the neural control of stiffness is unknown, but progress has been made in the field with multiple proposed models of how stiffness modulation may be accomplished by the nervous system. Limb stiffness has multiple components that must be controlled to produce the appropriate limb stiffness.

Combination of mechanics and neural control

Both the neural control and the mechanics of the limb contribute to its overall stiffness. The cocontraction of antagonistic muscles, posture of the limb, and stretch reflexes within the limb all contribute to stiffness and are affected by the nervous system.[1][6]

The stiffness of a limb is dependent on its configuration or joint arrangement.[1][6] For example, an arm that is slightly bent, it will deform more easily under a force directed from the hand to the shoulder than an arm that is straight. In this way, the stiffness of a limb is partially dictated by the limb's posture. This component of limb stiffness is due to the mechanics of the limb and is controlled voluntarily.

Voluntary vs. involuntary stiffness modulation

Some components of limb stiffness are under voluntary control while others are involuntary.[6] The determining factor as to whether a component of stiffness is controlled voluntarily or involuntarily is the timescale of that particular component's method of action. For example, stiffness corrections that happen very quickly (80-100 milliseconds) are involuntary while slower stiffness corrections and adjustments are under voluntary control. Many of the voluntary stiffness adjustments are controlled by the motor cortex while involuntary adjustments can be controlled by reflex loops in the spinal cord or other parts of the brain.[8][10][13]

Stiffness adjustments due to reflexes are involuntary and are controlled by the spinal cord while posture selection is controlled voluntarily.[6] However, not each component of stiffness is strictly voluntary or involuntary.[8] For example, Antagonistic muscle cocontraction can be either voluntary or involuntary. Additionally, because much of the legs' movements are controlled by the spinal cord and because of the larger neural delay associated with sending signals to the leg muscles, leg stiffness is more involuntarily controlled than arm stiffness.

Possible neural control models

Researchers have begun implementing controllers in into robots to control for stiffness. One such model adjusts for stiffness during robotic locomotion by virtually cocontracting antagonistic muscles about the robot's joints to modulate stiffness while a central pattern generator (CPG) controls the robot's locomotion.[15]

Other models of the neural modulation of stiffness include a feedforward model of stiffness adjustment. These models of neural control support the idea that humans use a feedforward mechanism of stiffness selection in anticipation of the required stiffness needed to accomplish a given task.[16]

Most models of the neural control of stiffness promote the idea that humans choose an optimal limb stiffness based on their environment or the task at hand. Studies postulate the humans do this in order to stabilize unstable dynamics of the environment and also to maximize the energy efficiency of a given movement.[6][14] The exact method by which humans accomplish this is unknown, but impedance control has been used to give insight into how humans may choose an appropriate stiffness in different environments and as they perform different tasks.[1] Impedance control has served as the basis for much of the work done in the area of determining how humans interact with their environment. The work of Neville Hogan has been particularly useful in this area as much of the work being done today in this area is based on his previous work.[1]

Applications in robotics

Neuroprosthetics and exoskeletons

Knowledge of human stiffness variation and stiffness selection has influenced robotic designs as researchers attempt to design robots that act more like biological systems. In order for robots to act more like biological systems, work is being done to attempt to implement stiffness modulation in robots so that they may interact more effectively with their environment.

State of the art neuroprosthetics have attempted to implements stiffness control in their robotic devices. The goal of these devices is to replace the limbs of amputees and allow the new limbs to adjust their stiffness in order to effectively interact with the environment.[17]

Additionally, robotic exoskeletons have attempted to implement similar adjustable stiffness in their devices.[18] These robots implement stiffness control for multiple reasons. The robots must be able to interact efficiently with the external environment but they must also be able to interact safely with their human user.[19] Stiffness modulation and impedance control can be leveraged to accomplish both of these goals.

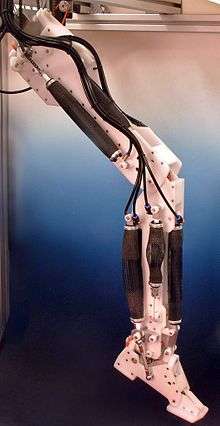

These devices achieve variable stiffness in various ways. Some devices use controllers and rigid servomotors to simulate variable stiffness. Other devices utilize specific flexible actuators to achieve a various levels of limb stiffness.

Actuation Techniques

These robotic devices are able to achieve variable stiffness through various mechanisms such as simulating stiffness variation through control of stiff actuators or by utilizing variable stiffness actuators. Variable stiffness actuators mimic biological organisms by changing their inherent stiffness.[2] These variable stiffness acutators are able to control their inherent stiffness in multiple ways. Some vary their stiffness much like humans do, by varying the force contribution of antagonistic mechanical muscles. Other actuators are able to adjust their stiffness by taking advantage of the properties of deformable elements housed within the actuators.

By utilizing these variable stiffness actuation technologies, new robots have been able to more accurately replicate the motions of biological organisms and mimic their energetic efficiencies.

See also

References

- Hogan, Neville (1985). "The Mechanics of Multi-joint Posture and Movement Control". Biological Cybernetics. 52 (5): 315–331. doi:10.1007/bf00355754.

- Van Ham, R.; Sugar, T.G.; Vanderborght, B.; Hollander, K.W.; Lefeber, D. (2009). "Compliant Actuator Designs". IEEE Robotics & Automation Magazine. 16 (3): 81–94. doi:10.1109/mra.2009.933629.

- Oliver, J.L.; Smith, P.M. (2010). "Neural Control of Leg Stiffness During Hopping in Boys and Men". Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology. 20 (5): 973–979. doi:10.1016/j.jelekin.2010.03.011.

- Lametti, Daniel R.; Houle, Guillaume; Ostry, David J. (2007). "Control of Movement Variability and the Regulation of Limb Impedance". Journal of Neurophysiology. 98 (6): 3516–3524. doi:10.1152/jn.00970.2007. PMID 17913978.

- Ferris, Daniel P.; Louie, Micky; Farley, Claire T. (1998). "Running in the Real World: Adjusting Leg Stiffness for Different Surfaces". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 265 (1400): 989–994. doi:10.1098/rspb.1998.0388. PMC 1689165. PMID 9675909.

- Trumbower, Randy D; Krutky, M.A.; Yang, B.; Perreault, E.J. (2009). "Use of Self-Selected Postures to Regulate Multi-Joint Stiffness During Unconstrained Tasks". PLoS ONE. 4 (5): e5411. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0005411. PMC 2671603. PMID 19412540.

- Butler, R.J.; Crowell, H.P.; Davis, I.M. (2003). "Lower Extremity Stiffness: Implications for Performance and Injury". Clinical Biomechanics. 18 (6): 511–517. doi:10.1016/s0268-0033(03)00071-8.

- Ludvig, Daniel P; Kearney, R.E. (2007). "Real-time estimation of intrinsic and reflex stiffness". IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering. 54 (10): 1875–1884. doi:10.1109/tbme.2007.894737. PMID 17926686.

- Heitmann S, Ferns N, Breakspear M (2012). "Muscle co-contraction modulates damping and joint stability in a three-link biomechanical limb". Frontiers in Neurorobotics. 5 (5): 1. doi:10.3389/fnbot.2011.00005. PMC 3257849. PMID 22275897.

- Nichols, T.R; Houk, J.C. (1976). "Improvement in linearity and regulation of stiffness that results from actions of stretch reflex". J. Neurophysiol. 39 (1): 119–142. doi:10.1152/jn.1976.39.1.119. PMID 1249597.

- Shemmell, Jonathan; Krutky, M.A.; Perreault, E.J. (2010). "Stretch sensitive reflexes as an adaptive mechanism for maintaining limb stability". Clinical Neurophysiology. 121 (10): 1680–1689. doi:10.1016/j.clinph.2010.02.166. PMC 2932821. PMID 20434396.

- Trumbower, RD; Finley, J.M.; Shemmell, J.B.; Honeycutt, C.F.; Perreault, E.J. (2013). "Bilateral impairments in task-dependent modulation of the long-latency stretch reflex following stroke". Clinical Neurophysiology. 124 (7): 1373–1380. doi:10.1016/j.clinph.2013.01.013. PMC 3674210. PMID 23453250.

- Dale Purves; et al., eds. (2007). Neuroscience (4th ed.). New York: W. H. Freeman. ISBN 978-0878936977.

- Burdet, E.; Osu, R.; Franklin, D.W.; Milner, T.E.; Kawato, M. (2001). "The central nervous system stabilizes unstable dynamics by learning optimal impedance". Nature. 414 (6862): 446–449. doi:10.1038/35106566. PMID 11719805.

- Xiong, Xiaofeng; Worgotter, F.; Manoonpong, P. "An adaptive neuromechanical model for muscle impedance modulations of legged robots". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Hu, Xiao; Murray, W.M.; Perreault, E.J. (2012). "Biomechanical constraints on the feedforward regulation of endpoint stiffness". Journal of Neurophysiology. 108 (8): 2083–2091. doi:10.1152/jn.00330.2012. PMC 3545028. PMID 22832565.

- Fite, Kevin; Mitchell, J.; Sup, F.; Goldfarb, M. (2007). "Design and control of an electrically powered knee prosthesis". Rehabilitation Robotics Conference.

- Van Der Kooij, H.; Veneman, J.; Ekkelenkamp, R. (2006). Design of a compliantly actuated exoskeleton for an impedance controlled gait trainer robot. Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society Conference of the IEEE. 1. pp. 189–93. doi:10.1109/IEMBS.2006.259397. ISBN 978-1-4244-0032-4. PMID 17946801.

- Kazerooni, Homayoon (1996). "The human power amplifier technology at University of California, Berkeley". Journal of Robotics and Autonomous Systems. 19 (2): 179–187. doi:10.1016/S0921-8890(96)00045-0.