Negombo Tamils

Negombo Tamils or Puttalam Tamils are the native Sri Lankan Tamils who live in the western Gampaha and Puttalam districts of Sri Lanka. They are distinguished from other Tamils from the island nation by their unique dialects, one of which is known as Negombo Tamil dialect. Other sub categories of native Tamils of Sri Lanka are Jaffna Tamils or Northern Tamils and Batticalao Tamils or Eastern Tamils from the traditional Tamil dominant North and East of the Island nation. Negombo is a principal coastal city in the Gampaha District and Puttalam is also the principal city within the neighbouring Puttalam District.[1][2][3][4]

Assimilation

The main feature of the Negombo Tamils is the continuing process of assimilation into the majority Sinhalese ethnic group, a process known as Sinhalisation. This process is enabled via a number of caste myths and legends.

In the Gampaha district ethnic Tamils have historically inhabited the coastal belt, as in the neighboring Puttalam district, which until the first two decades of the twentieth century had a substantial ethnic Tamil population, of whom the majority were Catholics and a minority were Hindus.[5][6][7] According to L.J.B. Turner, although the distinction between Sinhalese and Tamils of the present-day Sri Lanka is so marked, in the past there was considerable fusion between these ethnic groups. According to him the results of this fusion are most obvious on the western coast between Negombo and Puttalam, where a large proportion of the villagers, though they call themselves Sinhalese, speak Tamil and are undoubtedly of Tamil descent. According to local legends, their ancestors were captives from India or imported weavers and other artisans.[8][9]

This historic process was embraced by the educational policies of a local bishop, Edmund Peiris, who was instrumental in changing the medium of education from Tamil to Sinhala.[9][10][11]

Survival of Tamil heritage

Due to the bilingualism of some residents of both these districts, especially those who are traditional fishermen, the Tamil language survives as a lingua franca amongst migrating fishermen across the island.[1] It is estimated that the Negombo dialect of Tamil language is spoken by perhaps 50,000 people who otherwise identify themselves as Sinhalese. This number does not include others who may speak various varieties of the Tamil language north of Negombo city towards Puttalam.[1] Today most of those who retain their Tamil identity are Hindus and are mostly concentrated in a single coastal village called Udappu. This village has approximately 15,000 inhabitants and has become refuge for other Tamils displaced due to the Sri Lankan civil war from the rest of the country.[13] There are also some Tamil Christians belonging to various Christian sects (mostly Catholics) who maintain their Tamil heritage throughout both these districts in major cities such as Negombo, Chilaw, Puttalam and in villages such as Mampuri.[5]

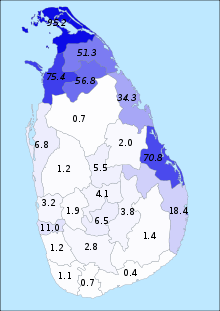

Tamil heritage is also maintained in place names in both these districts. Outside of the Tamil-dominated North East, Puttalam district has the highest percentage of place names of Tamil origin in Sri Lanka. There are also composite or hybrid place names in both these districts. The juxtaposition of Sinhala and Tamil place names indicated the peaceful coexistence of people of both language groups as well as the gradual assimilation process.[14] There are also numerous Hindu temples across the districts mostly dedicated to Hindu village deities such as Ayyanar, who is also worshiped as Ayyanayake by the Sinhalese people. Other deities include Kali, Kannaki and Lord Shiva, whose famous temple at Munneswaram was built by Raja Raja Cholan a Tamil king.

See also

- Colombo Chettys

- Bharatakula

- Karave

- Place names in Sri Lanka

References

- Contact-Induced Morphosyntactic Realignment in Negombo Fishermen’s Tamil Archived 2008-02-29 at the Wayback Machine By Bonta Stevens, South Asian Language Analysis Roundtable XXIII (October 12, 2003) The University of Texas at Austin

- Negombo fishermen's Tamil: A case of contact-induced language change from Sri Lanka by Bonta Stevens , Cornell University

- Roman-Dutch law versus Tesavalamai FERNANDO v. PROCTOR el al.

- Sri Lanka:History and Roots of Conflict by Jonathan Spencer

- Participation, Patrons and the Village: The case of Puttalam District Archived 2008-06-11 at the Wayback Machine by Jens Foell et al.

- Pearling, fishing and military heritage of Chilaw residents from India

- Susantha Goonetilleke, Sinhalisation: Migration or Cultural Colonization? Lanka Guardian Vol. 3, No. I, May I, 1980, pp. 22-29, and May 15 1980, pp. 18-19.

- 1921 Ceylon census by L.B. Turner (p202 of Vol I)

- Spencer, J, Sri Lankan history and roots of conflict, p. 23

- How Sri Lanka undermined infallibility of Pope John Paul II

- Kartikecu, Civattampi (1995). Sri Lankan Tamil society and politics. New Century Book House. p. 189. ISBN 81-234-0395-X.

- Records of Traditional Watercraft from South and West Sri Lanka, Gerhard Kapitan (G. Grainge & S. Devendra), pp. 22-46

- The Maravar Suitor Archived 2008-05-17 at the Wayback Machine By Henry Corea (The Sunday Observer)

- Kularatnam, K (April 1966). "Tamil Place Names in Ceylon outside the Northern and Eastern Provinces". Proceedings of the First International Conference Seminar of Tamil Studies, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia vol.1. International Association of Tamil Research. pp. 486–493.