National Bonsai Foundation

The National Bonsai Foundation (NBF) is a nonprofit organization that was created to sustain the National Bonsai and Penjing Museum. NBF also helps the United States National Arboretum showcase the arts of bonsai and penjing to the general public. The National Bonsai and Penjing Museum is located on the 446-acre (1.80 km2) campus of the U.S. National Arboretum in northeast Washington, D.C. Each year over 200,000 people visit the museum.[1] Distinguished national and international guests of various federal departments are also among the visitors.[2]

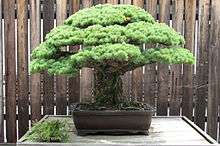

A western yellow pine (Pinus ponderosa) bonsai on display at the entrance to the National Bonsai and Penjing Museum | |

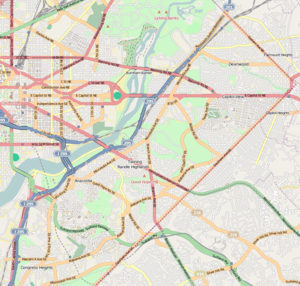

Location in Washington, D.C. | |

| Established | 1982 |

|---|---|

| Location | 3501 New York Avenue, N.E., Washington D.C. 20002 |

| Coordinates | 38.9124°N 76.9689°W |

Mission statement

"The National Bonsai Foundation is a section 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization established in 1982 to sustain the National Bonsai and Penjing Museum. It cooperates with the U. S. National Arboretum by offering financial support and advice to the museum.

This private/public collaboration between the Foundation and the Arboretum enables the museum to promote the art of bonsai and penjing to visitors through masterpiece displays and educational programs while also fostering intercultural friendship and understanding."[3]

History

In 1976, the country of Japan gave a gift of 53 bonsai trees to America for the United States Bicentennial. The trees were selected by the Nippon Bonsai Association, with financial assistance from the Japan Foundation. The trees arrived at the Potomac Bonsai Association, and volunteers worked with the staff of the U.S. National Arboretum to keep the trees in display condition. In 1979, Janet Lanman talked with Dr. John Creech, Director of the National Arboretum, about the possibility of adding American bonsai to the museum. Dr. Creech proposed this idea to well-known bonsai teacher Marion Gyllenswan. An independent body of bonsai authorities was assigned to review private bonsai collections, possibly as a part of a national collection. These bonsai authorities were called the National Bonsai Committee. In 1982, the National Bonsai Committee was reformed into the National Bonsai Foundation (NBF). The NBF recruited people from all across the country to be directors, with the members of the first board being Marybel Balendonck, Larry Ragle, Melba Tucker, Frederic Ballard, and H. William Merritt. MaryAnn Orlando served as the Executive Director and principal fundraiser for the NBF. Marion Gyllenswan was appointed the first President of the NBF (Frederic Ballard would be the second from 1990–1996 and Felix B. Laughlin would be the third from 1996–present).

In 1986, the ten-year anniversary of the gift from Japan, the National Bonsai Foundation announced that they would be building the American Bonsai Pavilion to complement the Japanese Pavilion, and to showcase a collection of North American bonsai. This became a reality on October 1, 1990 when the American Bonsai Pavilion was dedicated to two American bonsai masters. The Yuji Yoshimura Educational Center is a work space and a classroom. The John Y. Naka North American Pavilion provides the display area for the North American Bonsai Collection.[4]

With donations from the bonsai community, the National Bonsai and Penjing Museum grew greatly in the early 1990s. The Kaneshiro Tropical Conservatory (named for "Papa" Kaneshiro, the father of Hawaiian bonsai) was added in 1993 for delicate trees. A behind-the-scenes greenhouse was also added for trees in development.[5] The Mary E. Mrose Exhibit Gallery was completed in 1996, and the NBF website was launched three years later.

Awakening the Soul: The National Viewing Stone Collection (2000) became the first book published by the National Bonsai Foundation. The following year the NBF sponsored the first North American Bonsai Pot Competition for ceramic artists, published The Bonsai Saga: How the Bicentennial Collection Came to America by former U.S. National Arboretum Director, Dr. John Creech, and published a translation into English of Forest, Rock Planting & Ezo Spruce Bonsai by the Japanese bonsai master Saburo Kato. With significant funding from NBF, in 2003 the Maria Vanzant Upper Courtyard and the H. William Merritt Entrance Gate to the Kato Family Japanese Stroll Garden were dedicated. The NBF also became a membership organization that year, supported by annual dues as well as by contributions. A number of bonsai societies, related groups, and individuals then became members.[6] The NBF, along with the U.S. National Arboretum and the Potomac Bonsai Association, hosted the World Bonsai Friendship Federation's 5th World Bonsai Convention in Washington D.C. in late May 2005. Also that year, John Naka’s Sketchbook and the Proceedings of the International Symposium on Bonsai and Viewing Stones (which was held in 2002) were both published by NBF. The completion of the Rose Family Garden and the paving of the lower courtyard were accomplished with NBF funds.[7]

In 2011 the Campaign For The Japanese Pavilion: A Gift Renewed was established to raise funds for the renovation and improvement of that Pavilion which had been damaged over the years from exposure to the elements. Over the years, funds have also been used on occasion to purchase select pots from Japan for some of the trees in the collection, and new periodicals and historical reference volumes from Japan for the museum library.[8]

Collections and exhibits

The National Bonsai and Penjing Museum has four main collections: the Japanese, Chinese, and North American collections, and the viewing stones. There have been five curators of the museum so far: Robert F. Drechsler (1975–1996), Warren Hill (1996–2001), Jack Sustic (2002–2005), Jim Hughes (2005–2008), Jack Sustic (again, 2008–2016), and Michael James (2016–present).[10] In addition to the collections the museum also has pavilions, courtyards, and gardens. The National Bonsai and Penjing Museum also displays a number of rotating exhibits in the Mary E. Mrose Exhibit Gallery.[11] These ventures are supported by NBF officers, advisors, donors, staff members, and volunteers.[12]

Japanese Collection

This collection started with the 53 original trees from Japan.[13] These trees spent a year in quarantine after arrival, and on July 19, 1976 were dedicated in a ceremony with many dignitaries from Japan and the United States in attendance. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, acting on behalf of the American government, accepted the trees. The collection has grown to 63 trees and can be seen in the Japanese Pavilion from April to October. From November to March they can be seen in the Yee-sun Wu Chinese Pavilion.[14]

Chinese Collection

The Chinese Collection (also known as the Penjing Collection) is located in the Yee-sun Wu Chinese Garden Pavilion. This pavilion is named for Dr. Yee-sun Wu (1900–2005), who collected and designed penjing in Hong Kong. In 1983, Janet Lanman, an NBF Board Member, asked Dr. Wu if he would like to help include penjing in the museum. Dr. Wu was delighted at the idea, and gave funding to build a pavilion, as well as donating many penjing trees. In 1988 the museum was renamed National Bonsai and Penjing Museum.[15]

North American Collection

Most of the trees in the North American Collection are in the John Y. Naka North American Pavilion. The tropical species of this collection are in the Haruo Kaneshiro Tropical Conservatory. The 63-tree collection is composed of bonsai made entirely by North Americans. The John Y. Naka North American Pavilion was dedicated in 1990 to the American-born grand master John Y. Naka (1914–2004). His world-famous bonsai composition Goshin (seen right) is displayed at the entrance to the pavilion. The trees in this collection can be seen on display in spring, summer, and fall. In winter they are moved to the Chinese Pavilion.[16]

Viewing Stone Collection

In addition to the bonsai trees, the National Bonsai and Penjing Museum also has a world-class collection of viewing stones. Bonsai and viewing stones are closely related, as both show great respect for nature. When the small-scale plants and stones are combined, the whole of nature can be imagined via these magical miniature landscapes.

This collection began with six suiseki that accompanied the 53 original bonsai. The collection today has a total of 105 stones from all around the world. The stones can be seen in and around the Mary Mrose Exhibit Gallery. The Melba Tucker Suiseki and Viewing Stone Display Area has its stones periodically changed in themes.[17]

References

- National Bonsai and Penjing Museum

- "Museum Notes". NBF Bulletin. XXII (1–2): 4. 2001.

- "National Bonsai Foundation Mission". Archived from the original on 2008-05-12. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- National Bonsai Foundation History Milestones

- "Bonsai Collections". Archived from the original on 2017-07-02. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- National Bonsai Foundation Member Groups

- National Bonsai Foundation History Milestones

- "Museum Notes". NBF Bulletin. XXII (1–2): 4. 2001.

- "Hiroshima Survivor". National Bonsai Foundation. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- "National Bonsai Foundation Mission". Archived from the original on 2008-05-12. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- National Bonsai Foundation Exhibits

- National Bonsai Foundation Directors

- https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/world/this-390-year-old-bonsai-tree-survived-an-atomic-bomb/ar-BBllbHc?ocid=HPCDHP

- National Bonsai Foundation Japanese

- National Bonsai Foundation Chinese

- National Bonsai Foundation North American

- National Bonsai Foundation Viewing Stones

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to United States National Bonsai & Penjing Museum. |

- Official site of the National Bonsai Foundation

- NBF Bulletin (quarterly-semiannual newsletter)

- National Bonsai Foundation on Facebook

- Capital Bonsai Blog, featuring the collections of the National Bonsai and Penjing Museum

- The Bonsai Saga: How the Bicentennial Collection Came to America, by John Creech

- Video: '400-Year-Old Bonsai Survived Hiroshima Bombing' by Zulima Palacio

- Video: 'Place - Japanese Bonsai Garden at the National Arboretum' by Rupert Chappelle