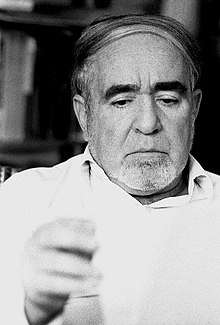

Nathan Zach

Nathan Zach (Hebrew: נתן זך) (born 1930) is an Israeli poet.[1]

Nathan Zach | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1930 (age 89–90) Berlin, Germany |

| Occupation | Poet |

| Nationality | Israeli |

| Notable awards | Bialik Prize Feronia Prize Israel Prize |

Biography

Born in Berlin, Zach immigrated to what was then known as Palestine in 1936 and served in the IDF as an intelligence clerk during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War.[1]

In 1955, he published his first collection of poetry (Shirim Rishonim, Hebrew: שירים ראשונים), and also translated numerous German plays for the Hebrew stage.[2][3]

Zach immigrated to Haifa as a child. At the vanguard of a group of poets who began to publish after Israel's establishment, Zach has had a great influence on the development of modern Hebrew poetry as editor and critic, as well as translator and poet. Distinguishing him among the poets of the generation of the 1950s and 1960s is his poetic manifesto Zeman veRitmus etsel Bergson uvaShira haModernit [Time and Rhythm in Bergson and in Modern (Hebrew) Poetry].[4] Zach has been one of the most important innovators in Hebrew poetry since the 1950s, and he is well known in Israel also for his translations of the poetry of Else Lasker-Schüler and Allen Ginsberg.[5]. The literary scholar Nili Rachel Scharf Gold has pointed to Zach an exemplar illustrating the role of "Mother Tongue" culture, in his case vis-a-vis German, on modern Hebrew literature.[6]

Zach's essay, “Thoughts on Alterman’s Poetry,” which was published in the magazine Achshav (Now) in 1959 was an important manifesto for the rebellion of the Likrat (towards) group against the lyrical pathos of the Zionist poets, as it included an unusual attack on Nathan Alterman, who was one of the most important and esteemed poets in the country. In the essay Zach decides upon new rules for poetry. The new rules that Zach presented were different from the rules of rhyme and meter which were customary in the nation’s poetry at the time.[7]

From 1960 to 1967, Zach lectured in several institutes of higher education both in Tel Aviv and Haifa. From 1968 to 1979 he lived in England and completed his PhD at the University of Essex. After returning to Israel, he lectured at Tel Aviv University and was appointed professor at the University of Haifa. He has been chairman of the repertoire board of both the Ohel and Cameri theaters.[8]

Awards and critical acclaim

Internationally acclaimed, Zach has been called "the most articulate and insistent spokesman of the modernist movement in Hebrew poetry".[9] He is one of the best known Israeli poets abroad.

- In 1982, Zach was awarded the Bialik Prize for literature.[10]

- In 1993, he was awarded the Feronia Prize (Rome).[9]

- In 1995, he was awarded the Israel Prize for Hebrew poetry.[11]

Racism and controversy

In July 2010 Zach was interviewed on Israel's Channel 10 and accused Sephardic Jews from Muslim countries of having an inferior culture to that of Jews from Europe; "The idea of taking people who have nothing in common arose. The one lot comes from the highest culture there is — Western European culture — and the other lot comes from the caves."[12] The racist comments resulted in a petition to remove his work from the educational curriculum and remove him from any academic positions.

Published works

- First Poems (1955)

- Other Poems (1960)

- All the Milk and Honey (1966)

- Time and Rhythm in Bergson and in Modern Poetry (1966)

- Theatre of the Absurd (1971) - London, Artist Book, collaboration with artist Maty Grunberg

- Book of Esther (1975) - London, free translation, collaboration with artist Maty Grunberg

- Northeasterly (1979)

- Anti-erasure (1984)

- Dog and Bitch Poems (1990)

- Because I'm Around (1996)

- Death of My Mother (1997)

References

- Tsipi Keller, Aminadav Dykman. Poets on the edge: an anthology of contemporary Hebrew poetry. Retrieved August 31, 2011.

- The Modern Hebrew Poem Itself. 2003. ISBN 0-8142-1485-1.

- Natan Zach; translated from the Hebrew by Peter Everwine and Schulamit Yasny-Starkman (1982). The static element: selected poems of Natan Zach. Atheneum. Retrieved August 31, 2011.

- Butt, Aviva. “The Earlier Poetry of Natan Zach.” Poets from a War Torn World. SBPRA, 2012: 16-26.

- Bill Morgan. I Celebrate Myself: The Somewhat Private Life of Allen Ginsberg. Retrieved August 31, 2011.

- Gold, Nili Rachel Scharf (2013). "Mother Tongue and Motherland in the Works of Natan Zach". Trumah: Zeitschrift der Hochschule für Jüdische Studien. 21: 59–68.

- Asher Reich: portrait of a Hebrew poet. Retrieved August 31, 2011.

- The static element: selected poems ... June 13, 2008. Retrieved August 31, 2011.

- "Natan Zach". Poetry International Web. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved August 31, 2011.

- "List of Bialik Prize recipients 1933–2004 (in Hebrew), Tel Aviv Municipality website" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-12-17.

- "Israel Prize Official Site – Recipients in 1995 (in Hebrew)".

- Armon, Ellie (April 21, 2011). "Renowned poet Natan Zach accused of racism after TV comments". Haaretz. Retrieved August 31, 2011.

External links

- Admiel Kosman: On terms of Time and the Theological perception of Zach: Reading the Poem ‘Ani Rotze Tamid Eynayim`, in Dorit Weissman (ed.), Makom LeShirah: http://www.poetryplace.org/index.php/online-magazine/-2011/gilayon-42/807