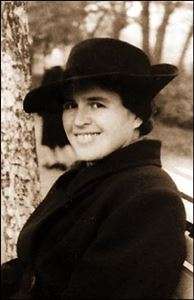

Natalya Baranskaya

Natalya Vladimirovna Baranskaya (Russian: Наталья Владимировна Баранская; January 31, 1908 – October 29, 2004) was a Soviet writer of short stories and novellas. Baranskaya wrote her stories in Russian and gained international recognition for her realistic portrayal of Soviet women's daily lives.

Natalya Baranskaya | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | January 31, 1908 St Petersburg, Russia |

| Died | October 29, 2004 (aged 96) Moscow, Russia |

| Occupation | short story writer |

| Language | Russian |

| Nationality | Soviet |

| Alma mater | Moscow State University |

Biography

Baranskaya was born in 1908 in St. Petersurg, Russia. She graduated in 1929 from Moscow State University with degrees in philology and ethnology. She became a war widow in 1943, when her husband died in World War II. She had two children and never married again. She did post-graduate work on the side while raising her children and pursuing a career as a museum professional. She worked at the Literary Museum and the Pushkin Museum in Moscow. She began writing stories after she retired from the museum in 1966, and her first story was published in 1968 in the Russian literary magazine Novy Mir.[1] She died in 2004 in Moscow, Russia.[2]

Published works

Baranskaya's most famous work is "A Week Like Any Other," a novella first published in Novy Mir in 1969. This story earned her international recognition.[1] It was published in the American magazine Redbook in 1971 under the title "Alarm Clock in the Cupboard," translated into English by Beatrice Stillman.[3] A different translation by Emily Lehrman appeared in The Massachusetts Review in 1974, this time under the title "A Week Like Any Other Week," which is a loose translation of the novella's original Russian title.[4]

The novella "A Week Like Any Other" is written as a first-person account of one week in the life of Olga Voronkova. The protagonist is a 26-year-old research scientist and a married mother of two who is juggling a full-time career and a seemingly never-ending list of obligations at home. Olga is in a constant rush and is often sleep deprived. Her days begin before 6 a.m., end after midnight, and are so busy that, at the end of each day, she cannot seem to find the time or energy to fix a hook that has fallen off her bra. She is forced to reflect on her daily life when she is confronted with a mandatory "Questionnaire for Women" at work—a survey that asks Olga (and all her female coworkers) to calculate time spent on housework, childcare, and leisure in a single week. About the leisure category, Olga jokes that her only remaining hobby is the sport of running: running here and there, to the store and to catch the bus, always with a heavy grocery bag in each hand. The "Questionnaire for Women" also requires Olga to calculate how many working days she missed in a year, and she feels self-conscious and guilty when she realizes that she has lost 78 working days due to either her son or her daughter being sick. The novella presents a detailed and realistic view of Soviet women's daily realities in the 1960s.

Baranskaya published over thirty short stories and novellas, many of them dealing with Soviet women's lives and problems.[1] Besides publishing stories in literary magazines, she published several collections. Her collections included A Negative Giselle (Отрицательная Жизель, 1977), The Color of Dark Honey (Цвет темного меду, 1977), and The Woman with the Umbrella (Женщина с зонтиком, 1981).

In 1989, a collection of seven of her works was published in the United States under the title A Week Like Any Other: Novellas and Stories, translated into English by Pieta Monks.[5][6] The lives of working women with children is a recurring theme in these stories, which were first published in Russian between 1969 and 1986. Baranskaya's focus jumps from character to character, and her stories develop slowly, through action and detail. "The Petunin Affair," told from a man's point of view, reveals the petty side of Soviet bureaucrats, while "Lubka" traces the reformation of a juvenile delinquent.

References

- McLaughlin, Sigrid (1989). "Natalya Baranskaya". In McLaughlin, Sigrid (ed.). The Image of Women in Contemporary Soviet Fiction. The Image of Women in Contemporary Soviet Fiction: Selected Short Stories from the USSR. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 111–122. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-20371-0_6. ISBN 978-1-349-20371-0.

- Natalya Baranskaya in Krugosvet Encyclopedia (in Russian)

- Baranskaya, Natalya (March 1971). "The Alarm Clock in the Cupboard". Redbook. Translated by Beatrice Stillman. pp. 179–201.

- Baranskaya, Natalya (1974). Translated by Emily Lehrman. "A Week like Any Other Week". The Massachusetts Review. 15 (4): 657–703. ISSN 0025-4878. JSTOR 25088483.

- Baranaskaya, Natalya (1989). A Week Like Any Other: Novellas and Stories. Translated by Pieta Monks. Seattle, WA: Seal Press. ISBN 0-931188-80-6. OCLC 19810952.

- McLaughlin, Sigrid (1991). "Women Writers of the Soviet Union". Slavic Review. 50 (3): 683–685. doi:10.2307/2499865. ISSN 0037-6779. JSTOR 2499865.