Nalakuvara

Nalakūvara, also known as Nalakūbara, appears in Hindu and Buddhist mythology as the brother of Maṇigrīva (also known as Manibhadra), the son of the yaksha king Kubera (also known as Vaiśravaṇa) and husband of Rambha. Nalakūvara often appears as a sexual trickster figure in Hindu and Buddhist literature.

| Nalakuvara | |

|---|---|

| Affiliation | Nalakuvara, Kuberaputra, Kamayaksha[2] |

| Abode | Alakapuri |

| Mantra | Om Kuberaputra Kamyukshaha Nalakubera Namah |

| Weapon | Bow and Arrow |

| Symbol | Cashewnut [3] |

| Day | Monday |

| Mount | Parrot |

| Personal information | |

| Parents | |

| Siblings | Manibhadra |

| Consort | Rambha |

| Children | Sumit, Chitrangdata |

Names

Various Sanskrit and Prakrit texts give the name "Nalakūvara", "Nalakūvala", "Narakuvera", and "Naṭakuvera" to describe the son of Kubera. The god also appears in Chinese texts as "Nazha", and later "Nezha", a shortened transliteration of the word "Nalakūvara".[4]

Mythology

In Hinduism

In the Rāmāyaṇa

In the Rāmāyaṇa, Nalakūvara's would be wife Rambha was sexually assaulted by his uncle, Rāvaṇa. In some versions of the Ramayana, Nalakūvara curses Rāvaṇa, so that if Rāvaṇa touches any woman without permission, his heads would explode. This curse protected the chastity of Sītā, the wife of Rāma, after she was kidnapped by Rāvaṇa.

In the Bhagavata Purāṇa

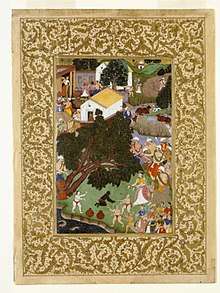

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

In the Bhagavata Purana, Nalakūvara and his brother Manigriva are cursed by the sage Narada into becoming trees.[5] They are later liberated by the child-god Krishna. They were playing, in nudity, in the Ganges with celestial maidens when Narada walked by after a visit with Vishnu. Upon seeing Narada, the maidens covered themselves, while Nalakūvara and Maṇigrīva were too intoxicated to notice Narada, and remained unclothed. According to some accounts, Narada pitied the brothers for wasting away their lives through their excessive indulgence in women and wine. In order to help the brothers realise their mistake, Narada cursed them into two Marutu Trees. Narada wished for the brothers to meet Lord Krishna after many years, who would be able to liberate them from the curse. In other accounts, it is said that Narada is so offended by the brothers’ lack of dignity and respect that he cursed them into trees. After the two brothers pleaded with Narada, he consented that they could be liberated if Krishna touched them.

Many years later, when Krishna was in his infancy, his mother Yashoda had tied him to a mortar in order to prevent him from eating dirt. Krishna dragged the mortar along the ground until it became wedged between two trees. These trees happened to be Nalakūvara and Maṇigrīva, and upon contact, they returned to their original form. The brothers then paid homage to Lord Krishna, apologized for their previous mistakes, and departed.[6]

In Buddhism

In the Kākātī Jātaka story, Nalakūvara (here Naṭakuvera), appears as the court musician of the king of Benares. After the King's wife, Queen Kākātī, is kidnapped by the Garuḍa King, the King of Benares sends Naṭakuvera to look for her. Naṭakuvera hides within the plumage of the Garuḍa King, who carries Naṭakuvera to his nest. Once he has arrived, Naṭakuvera has sex with Queen Kākātī. Afterwards Naṭakuvera returned to Benares in the Garuḍa's wing, and composed a song telling of his experiences with Kākātī. When the Garuḍa hears the song, he realises that he has been tricked, he brings Kākātī back home to her husband.[7]

Tantric masters invoked Nalakūvara as the commander of Kubera's army of yakṣas. He appears in the tantric text "Great Peacock-Queen Spell," which portrays him as a heroic yakṣa general and invokes Nalakūvara's name as a way to cure snakebites. Some versions of the "Great Peacock-Queen Spell" (Mahāmāyūrīvidyārājñī and the "Amogha-pāśa" give Nalakūvara the title "Great Yakṣa General." [8] Nalakūvara appears in two other tantric texts: "The Yakṣa Nartakapara’s Tantra," and "The Great Yakṣa General Natakapara’s Tantric Rituals." [9]

Worship in China and Japan

_(15513109434).jpg)

Nalakūvara was transmitted through Buddhist texts into China, where he became known as Nezha (known earlier as Nazha). In Chinese mythology, Nezha is the third son of the Tower King, so many people also called Nezha as the third prince. Nezha is also called "Marshal of the Central Altar" (Chinese: 中壇元帥). Nezha is a child-god in folk legend, his arms are made of lotus roots, he fights with bad guys, Nezha is a character with fresh blood and bones. Meir Shahar has traced the etymology of the word Nezha, showing that the name Nazha is a shortened (and slightly corrupted) transcription of the Sanskrit name "Nalakūbara." [10] It has been suggested by Shahar that the legends surrounding Nezha are a combination of the mythology of Nalakūvara and the child-god Krishna (Bala Krishna).

Nezha is a well-known Taoist deity in Japan. The Japanese refer to Nezha as Nataku or Nata, which came from the readings of Xiyouji or Seiyuki (西遊記) in Japanese.

See also

References

- Discussion with Indian NorthernEastern Mythologyist Samwel Debbarma

- Discussion with Indian NorthernEastern Mythologyist Samwel Debbarma

- Discussion with Indian NorthernEastern Mythologyist Samwel Debbarma

- Shahar, Meir (2014). "Indian Mythology and the Chinese Imagination: Nezha, Nalakubara, and Krshna". In John Kieschnick and Meir Shahar (ed.). India in the Chinese Imagination. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-8122-4560-8.

- Parmeshwaranand. Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Puranas, Volume 1. Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- Shahar, Meir (2014). "Indian Mythology and the Chinese Imagination: Nezha, Nalakubara, and Krshna". In John Kieschnick and Meir Shahar (ed.). India in the Chinese Imagination. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-8122-4560-8.

- Malalasekera, G.P. Dictionary of Pali Proper Names, Vol. 1. p. 559. Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- Shahar, Meir (2014). "Indian Mythology and the Chinese Imagination: Nezha, Nalakubara, and Krshna". In John Kieschnick and Meir Shahar (ed.). India in the Chinese Imagination. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 27–29. ISBN 978-0-8122-4560-8.

- Shahar, Meir (2014). "Indian Mythology and the Chinese Imagination: Nezha, Nalakubara, and Krshna". In John Kieschnick and Meir Shahar (ed.). India in the Chinese Imagination. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-8122-4560-8.

- Shahar, Meir (2014). "Indian Mythology and the Chinese Imagination: Nezha, Nalakubara, and Krshna". In John Kieschnick and Meir Shahar (ed.). India in the Chinese Imagination. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-8122-4560-8.