Nagarathar

The Nagarathar (also known as Nattukottai Chettiar) is a Tamil caste found native in Tamil Nadu, India. They are a mercantile community who including to commerce also traditionally are involved in banking and money lending.[1]

Annanmalai Chettiar, Raja of Chettinad | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| India: Chettinad region of Tamil Nadu, Chennai | |

| Languages | |

| Tamil | |

| Religion | |

| Hinduism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Tamil people, Dravidian people |

They use the title Chettiar and are traditionally concentrated in modern region Chettinad.[2] They have since the 19th century been prominent entrepreneurs who funded and built several Hindu temples, schools, colleges and universities.[3]

Etymology

The term Nagarathar literally means "town-dweller".[4] Their title, Chettiar, is a generic term used by several mercantile groups which is derived from the ancient Tamil term etti (bestowed on merchants by the Tamil monarchs).[5]

Since they gained a reputation for living in mansions that were constructed in the 19th centuries and late 20th centuries, are they also known as Nattukottai Chettiar.[6] The term Nattukottai literally means "country-fort" in reference to their fort-like mansions.[4]

History

Nattukottai Nagarathars are Vaishyas (Vyshya)[7] originally from Naganadu. This ancient land Naganadu is believed to be destroyed (either in an earthquake or floods) and this place was either North or North West of Kanchipuram. It is believed to be to the South of present-day Andhra Pradesh.[8]

Nagarathars migrated and lived in the following places:

· Kanchipuram (Thondai Nadu) - From 2897 BC for about 2100 years

· Kaveripoompatinam (Poompuhar) (Chola Kingdom) - From 789 BC for about 1400 years.

· Ongarakudi (Karaikudi) (Pandiya Kingdom) - From 707 AD onwards.

When they were in Naganadu these Dhana Vaishyas had three different divisions:

1. Aaru (Six) Vazhiyar

2. Ezhu (Seven) Vazhiyar

3. Nangu (Four) Vazhiyar

All these three divisions were devoted to Emerald Ganesha (மரகத விநாயகர்). Only after they migrated to the Pandya_Kingdom they were called as Ariyurar, Ilayatrangudiyar, and Sundrapattanathar.

Nagarathars of Ilayatrangudiyar were later called as Nattukottai Nagarathar. Ariyurar Nagarathars further split into 3 divisions: Vadakku Valavu, Therku Valavu and Elur Chetty (Nagercoil). Sundrapattanathar Nagarathars migrated to Kollam district in Kerala and their history is completely lost now since there was no record keeping.[9]

The Nagarathar or Nattukkottai Chettiar were originally salt traders and historically an itinerant community of merchants and claim Chettinad as their traditional home.[10] How they reached that place, which at the time comprised adjacent parts of the ancient states of Pudukkottai, Ramnad and Sivagangai, is uncertain, with various communal legends being recorded. There are various claims regarding how they arrived in that area.[11] Among those are a fairly recently recorded claim that they were driven there because of persecution by a Chola king and an older one, recounted to Edgar Thurston, that they were encouraged to go there by a Pandyan king who wanted to take advantage of their trading skills. The legends converge in saying that they obtained the use of nine temples, with each representing one exogamous part of the community.[11]

The traditional base of the Nattukottai Nagarathars is the Chettinad region of the present-day state of Tamil Nadu. It comprises a triangular area around north-east Sivagangai, north-west Ramnad and south Pudukkottai.

They may have become maritime traders as far back as the 8th century CE. They were trading in salt and by the 17th century, European expansionism in South East Asia during the next century fostered conditions that enabled the community to expand its trading enterprises, including as moneylenders, thereafter.[1][11] By the late 18th century expanded them to inland and coastal trade in cotton and rice.[12]

In the 19th century, following the Permanent Settlement, some in the Nagarathar community wielded considerable influence in the affairs of the zamindar (landowners) elite. There had traditionally been a relationship between royalty and the community based on the premise that providing worthy service to royalty would result in the granting of high honours but this changed as the landowners increasingly needed to borrow money from the community in order to fight legal battles designed to retain their property and powers. Nagarathars provided that money as mortgaged loans but by the middle of the century they were becoming far less tolerant of any defaults and were insisting that failure to pay as arranged would result in the mortgaged properties being forfeited.[13] By the 19th century were their business activities developed into a sophisticated banking system, with their business expanding to parts of Southeast Asian countries such as Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Singapore, Indonesia and China.

Divisions

Multiple break-away communities exist among Nagarathars. The notable ones happened over a period of past 1300 years are mentioned here:

- Uruthikottai Vattagai Nagarathars

- Murayur Nagarathars

- Palayapatti Nagarathars

- Athangudi Nagarathars

- Ariyurar or Aruviyur Nagarathar Vadakku Valavu

- Ariyurar or Aruviyur Nagarathar Therkku Valavu

- Ariyurar – Elur Chetty

- Sundarapattanathar Nagarathar

Among all these divisions only Uruthikottai Vattagai Nagarathars have proper evidences and record keeping.[9]

Uruthikottai Vattagai Nagarathar

This incident took place on 12-July-1823 circa 200 years ago. It was the customary practice of Nagarathars in the olden days to congregate in a certain pre-arranged place to discuss any matter concerning the Nagarathar community. On 12-July-1823 (that is Tamil year Subhanu (சுபானு), Aani (ஆனி) month, 29th day), one such assembly was convened by Nagarathars of 96 villages at Unjanai, a small village near Devakottai in between Mathur and Iluppakudi. For that assembly, one prominent Chettiar Eriyur Kakkai Vellayan Chetty came late. He galloped into the assembly on horseback in haste, created a maelstrom of dust that swirled and engulfed the patiently waiting Nagarathars. He was unapologetic. The Assembly was outraged at his disrespect, lack of decorum and lateness. A fine was imposed and an apology was demanded prior to commencing.[14]

But he arrogantly refused to accept the directive. Instead, he used his considerable power and position to influence his reluctant relatives and close family into breaking away from the main Nagarathar community.

Ever since this incident in 1823 and subsequent fallout, this breakaway group was deemed segregated and privileges of belonging to the greater Nagarathar community revoked. One of the punitive measures meted out was the cessation of the custom of officially registering the marriages in the respective temples. The issuing of garlands from these temples in blessing and recognition of the newly married couples as a family unit (“pulli”) was also halted. The most severe punitive measure was the non-acknowledgement of the very existence of this segregated minority of Nagarathars in the official count of units (‘pullis”) of the temples.[15]

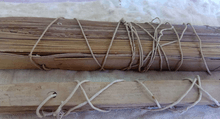

This minority group came to be known as Uruthikottai Vattagai Nagarathars. Among the 8 villages they settled down initially Uruthikottai was a prominent place in Sivagangai District those days.[16] They wrote their own rules and regulations and the same has been imprinted in dry palm-leaf as practised in those days. These palm-leaves are safeguarded to date. (Please refer to the images of these palm-leaves). As mentioned in this palm-leaf, initially they settled in the following villages: Uruthikottai, Thittukottai, Avarangudi, Karungulam, Panakkarai, Sarugani (Sarakanei), Eriyur and Surakudi. Over the period they vacated some of these villages and finally settled in the following 9 villages:[17]

- Avarangudi

- Eriyur

- Karungulam

- Kumaravelur

- O. Pudur (Okkur Pudur)

- Seenamangalam

- Shanmuganathapatnam (Koilampatti)

- S. Sockanathapuram (Poradappu)

- Surakudi

Out of 9 Nagarathar temples, this break-away Nagarathars group of 104 families belong to only four Nagarathar temples, namely Ilayathangudi, Mathur, Vairavanpatti and Pillayarpatti. Today the total number of families has grown from 104 to nearly 1400. Marriage alliances happen within Uruthikottai Vattagai Nagarathars only and marrying outside the community (Vattagai) is banned.

Evidences

Pudhuvayal Nachathal Padaippu

Padaippu is undertaken by relatives (Pangali பங்காளிகள்) of the same bloodline. This function is an offering and prayers to the ancestors. This is convened periodically on a predetermined date mostly at the native village or temple.

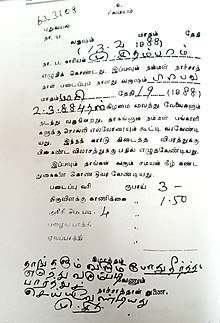

Nachathal Padaippu belonging to Vairavan temple is done at Puduvayal village every year during the Tamil month Maasi (மாசி). Though some Nagarathars of Vairavan Temple broke away from the mainstream in 1823 they still participate in this important function. The official invitation (Please refer to the invitation image) received by Vairavan Kovil Nagarathars of Uruthikottai Vattagai each year is strong evidence.[17]

Nagarathar Sermon

As customary in Nagararathar community males get their sermon in Padharakudi Monastery (மடம்) and females get theirs in Thulavur. The same is followed by Uruthikottai Vattagai Nagarathars till this date. Please refer to the letter written by the head of Thulavur Madam to Mr T. Kumarappa.[9]

Kundrakudi Charity

Annual food charity function (அன்னதானம்) is conducted at Kundrakudi Temple by collecting tax (Pulli Vari) from all Nattukottai Nagarathars. Similarly, such tax demands are sent to all Uruthikottai Vattagai Nagarathars also. Maheswara Pooja is done at this time and several Nagarathars including from Uruthikottai Vattagai participate in this function.[17]

Disciplinary Action

About 90 years ago one Kaluvathan Chetty of Kumaravelur (Uruthikottai Vattagai) was demanded to appear in person and pay a fine by Nattukkottai Nagarathars at Kovilur Nagarathar assembly for committing a social offence. He admitted his offence and obeyed and eventually he paid the penalty of Rs.650/-[14]

Nagarathar Rituals, Customs, and Traditions

These minority Nattukkottai Nagarathars retained their traditional values and customs in original form as aborigines of the Nattukkottai Nagarathar community. Not one iota of difference can be traced in the rituals, customs and traditions between the mainstream and this Uruthikottai Vattagai Nagarathars except of course some minor changes as per local convenience and preferences. But these small changes are prevalent even among the mainstream Nagarathars from one Vattagai to another.[18][19]

These break-away group also observe typical Nagarathar functions like Pudhumai (புதுமை) Kaarthigaisupadi (கார்திகைச்சூப்படி), Thiruvadhirai (திருவாதிரை), Magar Nonbu (மகர்நோன்பு) and of course Pillayar Nonbu (பிள்ளையார் நோன்பு).

Religious influence

The nine temples connected with the Nagarathar community include: Ilayathakudi, Iluppaikkudi, Iraniyur, Mathur, Nemam, Pillayarpatti,[20] Soorakudi, Vairavan, and Velangudi.[21]

See also

References

- Haellquist (21 August 2013). Asian Trade Routes. Routledge. p. 150. ISBN 9781136100741.

- Agesthialingom, Shanmugam; Karunakaran, K. (1980). Sociolinguistics and Dialectology: Seminar Papers. Annamalai Univ. p. 417.

- Ramaswami, N. S. (1988). Parrys 200: A Saga of Resilience. Affiliated East-West Press. p. 193. ISBN 9788185095745.

- Contributions to Indian Sociology. 36. Contributions to Indian Sociology: Occasional Studies: Mouton. 2002. p. 344.

- West Rudner, David (1987). "Religious Gifting and Inland Commerce in Seventeenth-Century South India". The Journal of Asian Studies. 46 (2). p. 376. doi:10.2307/2056019. JSTOR 2056019.

- Indian & Foreign Review. Publications Division of the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. 1986. p. 48.

- Sripati Chandrasekhar. The Nagarathars of South India: an essay and a bibliography on the Nagarathars in India and South-East Asia, Volume 1. Macmillan, 1980. p. 22.

- Singaravelu, Mudhaliar (1899). Abimana Chinthamani. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services.

- Pattu Veshti Ramanathan, Chettiar (2015). Analytical History of Nagarathar(நகரத்தார்களின் பகுத்தாய்ந்த வரலாறு). Sivakasi: Surya Print Solutions.

- Chaudhary, Latika; Gupta, Bishnupriya; Roy, Tirthankar; Swamy, Anand V. (20 August 2015). A New Economic History of Colonial India. Routledge. ISBN 9781317674320.

- Pamela G. Price (14 March 1996). Kingship and Political Practice in Colonial India. Cambridge University Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-521-55247-9.

- Chaudhary, Latika; Gupta, Bishnupriya; Roy, Tirthankar; Swamy, Anand V. (20 August 2015). A New Economic History of Colonial India. Routledge. ISBN 9781317674320.

- Pamela G. Price (14 March 1996). Kingship and Political Practice in Colonial India. Cambridge University Press. pp. 103–104. ISBN 978-0-521-55247-9.

- MR M KR M, Somasundaram (2003). Naam Nammai Sera. Karaikudi: Meyyappan Offset Printers. pp. 7–9.

- Madurai Nagarathar, Sangam. History of Uruthikottai Vattagai (உறுதிக்கோட்டை வட்டகை வரலாறு). Madurai.

- Shree Niramba Azhagiya, Desika Swamigal (1994). History of Atheenam and Nagarathar (ஆதீன வரலாறும் நகரத்தார் வரலாறும்). Thulavur Karaikudi: Meenakshi Printers. p. 47.

- Thiagarajan, V.N. (1989). Uruthikottai Vattagai Nagarathar (உறுதிக்கோட்டை வட்டகை நகரத்தார் - நாட்டுக்கோட்டை நகரத்தார்களே ! ஆதாரங்கள் கையேடு.). Coimbatore. p. 4.

- Nagarathar Malar (நகரத்தார் மலர்). 15 November 1988. p. 19.

- Somalay (1984). Chettinadum Senthamizhum (செட்டிநாடும் செந்தமிழும்). Madras: Vaanathi Publisher. p. 11.

- Aline Dobbie (2006). India: The Elephant's Blessing. Melrose Books. p. 101. ISBN 1-905226-85-3.

- "Chettinad's legacy". Frontline. 20 November 2018. Retrieved 27 December 2018.

Resources

- Rajeswary Brown. (1993). Chettiar capital and Southeast Asian credit networks in the inter-war period. In G. Austin and K. Sugihara, eds. Local Suppliers of Credit in the Third World, 1750-1960. New York: St. Martin's Press.

- David Rudner. (1989). "Banker's Trust and the culture of banking among the Nattukottai Chettiars of colonial South India". Modern Asian Studies 23(3), 417-458.

- David West Rudner (1994). Caste and Capitalism in Colonial India: The Nattukottai Chettiars. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-08350-9.

- Heiko Schrader. (1996). "Chettiar finance in Colonial Asia". Zeitschrift fur Ethnologie 121, 101-126.

- Yūko Nishimura (1998). Gender, Kinship And Property Rights: Nagarattar Womanhood in South India. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-564273-5.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nagarathar. |