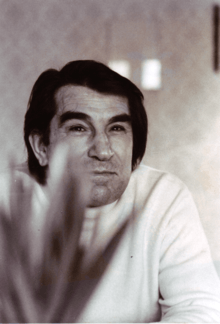

Nûredin Zaza

Nûredin Zaza (born 15 February 1919; Maden – 7 October 1988; Lausanne) was a Kurdish politician, writer and poet. Zaza was a co-founder of the Kurdistan Democratic Party of Syria and a founding member of the Kurdish Institute of Paris.[1]

Nûredîn Zaza | |

|---|---|

| |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1919 Maden, Elazığ, Ottoman Empire |

| Died | 1988 Bussigny, Lausanne, Switzerland |

| Political party | Kurdistan Democratic Party of Syria (1957–1963) |

| Alma mater | Lausanne University |

Biography

Born in 1919 to a middle-class family[2] in the Kurdish town of Maden in the years preceding the fall of the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, he saw his father and brother getting arrested by the Atatürk regime for having supported the Sheikh Said rebellion and the Ararat rebellion. Following, in 1930, he was sent into exile to Syria together with his brother Ahmed Nafez Zaza.[3] There, the brothers found support of the Bedir Khan family.[4]

After spending a year in jail in British Iraq, he went to Beirut and later Switzerland for his studies. In Switzerland, he also founded an association for Kurdish students in Europe before returning to Syria. In Syria, he prepared a party program together with Osman Sabri,[5] took part in establishing Kurdistan Democratic Party of Syria (KDPS) in 1957[3] and was its president by 1958.[6] He also wrote for the magazine Hawar of the Bedir Khan brothers[3] and contributed to the modernization of the Kurdish language.[7][8] Zaza was also a member of Xoybûn and broadcast a radio program with Kamuran Alî Bedirxan during this period.[9][10] In September 1962, he got briefly arrested by Syrian authorities, accusing him of supporting the Kurdish uprising in neighboring Iraq .[11] After being jailed again in 1965 and the intensified Turkish threats, Zaza fled to Switzerland in July 1970 – the same country he had studied in.

Zaza wrote his dissertation on Emmanuel Mounier in 1955 in at the Lausanne University.[12] Zaza's brother Suphi Ergene was a parliamentarian in the Turkish Parliament representing Elazığ district for the Democrat Party from 1954 to 1957.[13][14]

Selected literature

- Nûredin Zaza (1955). "Etude critique de la notion d'engagement chez Emmanuel Mounier". Histoire des Idées et Critique Littéraire (in French). Librairie Droz. 5079. ISSN 0073-2397.

- Nûredin Zaza (1974). Contes et poèmes kurdes (PDF) (in French). Geneva: Éditions Peuples et Création. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- Nûredin Zaza (1982). Ma vie de kurde: ou le cri du peuple kurde (in French). Éditions P.M. Favre. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- Nûredin Zaza (1995). Keskesor – Kurteçîrok (PDF) (in Kurdish). Stockholm: Nûdem. ISBN 91-88592-065. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

References

- "Institut kurde de Paris – bulletin de liaison et d'information" (PDF) (in French) (43-44-45). Paris. 1988. Retrieved 26 March 2020. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Gérard Chaliand (1994). The Kurdish Tragedy. Zed Books. p. 85. ISBN 9781856490993. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

978185649099

- Gorgas, Jordi Tejel (2007), 134

- Henning, Barbara (2018). Narratives of the History of the Ottoman-Kurdish Bedirhani Family in Imperial and Post-Imperial Contexts: Continuities and Changes. University of Bamberg Press. p. 535–536. ISBN 978-386309-551-2.

- Allsopp, Harriet (2014). The Kurds of Syria: Political Parties and Identity in the Middle East. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-78076-563-1.

- Allsopp, Harriet (2014),p.75

- Brodsky, Joseph, ed. (1997). Ecrivains en prison (in French). Labor et Fides. p. 246. ISBN 9782830908756.

- Özlem Belçim Galip (2015). Imagining Kurdistan: Identity, Culture and Society. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 41.

- "Nureddîn Zaza zerrê kurdan de yo". Yeni Özgür Politika (in Kurdish). 7 October 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- Martin Strohmeier (2003). Crucial Images in the Presentation of a Kurdish National Identity: Heroes and Patriots, Traitors and Foes. Brill. p. 175. ISBN 9789004125841.

- Michael M. Gunter (2014). Out of Nowhere: The Kurds of Syria in Peace and War. London: Oxford University Press. p. 26. ISBN 9781849044356. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- "Zaza 101 yaşında". Yeni Özgür Politika (in Turkish). 15 January 2020. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- Mehmet Ö. Alkan (2018). "1945–1960 Arası 1946, 1950, 1954 ve 1957 Genel Seçimlerinde Doğu'da DP-CHP Rekabeti" (PDF) (in Turkish). Kırklareli University: 5. Retrieved 27 March 2020. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Erol Tunçer / Bülent Tunçer. "Meclis Aritmetiğinde Yaşanan Değişim (1943–1960)" (PDF). TESAV. p. 89. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

Further reading

- Konê Res. Dr. Nûredîn Zaza (Kurdê Nejibîrkirinê) – 1919–1988 (in Kurdish). Sitav yayınevi. ISBN 9786057920096.

- "Noureddine Zaza (1920-1988)" (in French). Bibliothèque nationale de France. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- Omar Şêxmûs (18 February 2019). "Nûredîn Zaza: Rewşenbîr, siyasetvan û mirov" (in Kurdish). Kurdistan24. Retrieved 27 March 2020.