Mystical marriage of Saint Catherine

The mystical marriage of Saint Catherine (or "Mystic") covers two different subjects in Christian art arising from visions received by either Catherine of Alexandria or Catherine of Siena (1347–1380), in which these virgin saints went through a mystical marriage wedding ceremony with Christ, in the presence of the Virgin Mary, consecrating themselves and their virginity to him.

The Catholic Encyclopaedia notes that such a wedding ceremony "is but the accompaniment and symbol of a purely spiritual grace", and that "as a wife should share in the life of her husband, and as Christ suffered for the redemption of mankind, the mystical spouse enters into a more intimate participation in His sufferings." [1] Catherine of Alexandria was martyred, while Catherine of Siena received the stigmata.

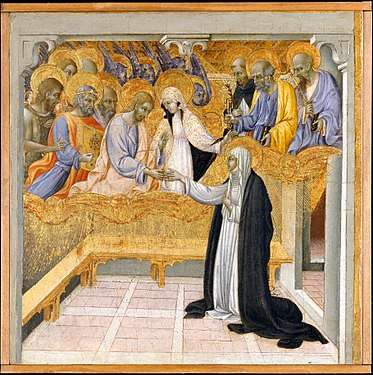

Both subjects are frequent subjects in Christian art; the scene usually includes one of the Saint Catherines and either the infant Jesus held by his mother or an adult Jesus. Very rarely both saints are shown in a double ceremony (as at right). Saint Catherine of Alexandria is invariably dressed as a princess in rich clothes, often with a crown, and normally with loose long blonde hair and carrying a martyr's palm, sometimes with her attribute of a wheel; Saint Catherine of Siena is shown as a Dominican nun in white with a black over-robe open at the front, so it is usually easy to tell which saint is depicted.[2]

History

Although Saint Catherine of Alexandria was supposed to have lived in the third and fourth centuries, the story of her vision appears first to be found in literature after 1337, over a thousand years after the traditional dating of her death, and ten years before Catherine of Siena was born.[3] It appears in later versions of the popular Golden Legend, but the earliest version of the account there seems to be in an English translation of 1438.[4]

The Barna da Siena panel at right was painted within a few years of the first literary mentions. Although she is a very popular saint in Eastern Orthodoxy, the marriage is not a traditional subject in Orthodox icons. In Western art the vision of Saint Catherine of Alexandria usually shows the Infant Christ, held by the Virgin, placing a ring (one of her attributes) on her finger, following some literary accounts, although in the version in the Golden Legend he appears to be adult, and the marriage takes place among a great crowd of angels and "all the celestial court",[5] and these may also be shown.

Saint Catherine of Siena would have been familiar with this story – the Barna da Siena panel shown was painted in Siena a few years before she was born – and she is recorded as praying as a child that she would have a similar experience, which she eventually did. She was "a devout woman whose imagination was stimulated unconsciously by religious images she had seen previously", as was also clear from the form of her stigmata as described by her.[6] Christ may be depicted as either an infant or adult in her scenes.[7]

She was canonized in 1461, though the Giovanni di Paolo picture below may predate this; it is also Sienese.[8] The fresco by Spinello Aretino or a follower in the Cialli-Sernigi chapel of Santa Trinita in Florence certainly predates the canonization by several decades. However, unlike the Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine of Alexandria, there were no large monumental images, such as the main panel of an altarpiece, of the Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine of Siena until 1528, when the Siennese painter Domenico Beccafumi painted one for the church of Santo Spirito in Siena.[9]

A mystical marriage to Christ is also an attribute of Saint Rosa of Lima (died 1617), and many other saints have reported such visions.

Giovanni di Paolo, The Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine of Siena

Giovanni di Paolo, The Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine of Siena- Master of the Legend of Saint Lucy, late 15th century, Brussels, Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium.

- The Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine, 1515/20, unknown Southern Netherlandish artist, Hamburger Kunsthalle

Clemente de Torres, c. 1700, Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine of Siena

Clemente de Torres, c. 1700, Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine of Siena

Works with articles

- Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine (Correggio, Paris), mid-1520s painting in the Louvre, Paris

- Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine (Correggio, Naples), c.1520 painting in the National Museum of Capodimonte, Naples

- Marriage of St. Catherine (Filippino Lippi), 1503 painting in the Basilica di San Domenico, Bologna, Italy

- Mystical Marriage of Saint Catherine (Michelino da Besozzo), c.1420 painting in the Pinacoteca Nazionale of Siena, Italy

- Three by Parmigianino:

- Mystical Marriage of Saint Catherine (Parmigianino), known as the Bardi Altarpiece, c.1521 painting in the church of Santa Maria at Bardi, Emilia-Romagna, Italy

- Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine (Parmigianino, Louvre)

- Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine (Parmigianino, National Gallery)

Notes

- "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Mystical Marriage".

- Earls, 56–57, 203

- Lucetta Scaraffia, Gabriella Zarri. Women and faith: Catholic religious life in Italy from late antiquity to the present, p.80, Harvard University Press, 1999, ISBN 0-674-95478-5, ISBN 978-0-674-95478-6, Google books

- Blum, Shierley Nielson, Early Netherlandish Triptychs, p. 155, note 26, University of California Press, 1969, google books

- Life of St "Katherine" in William Caxton's English version of the Golden Legend.

- Hall, 214

- Earls, 57

- MMA New York

- Jenkens, 179

References

- Earls, Irene. Renaissance art: a topical dictionary, Greenwood Publishing Group, 1987, ISBN 0-313-24658-0, Google books

- Hall, James. A History of Ideas and Images in Italian Art, John Murray, London, ISBN 0-7195-3971-4

- Jenkens, A. Lawrence. Renaissance Siena: art in context, Truman State University Press, 2005, ISBN 1-931112-43-6, ISBN 978-1-931112-43-7, Google books

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to |