Mutiny at Sucro

The Roman army's mutiny at Sucro, a no longer existing ancient fort in Spain, took place in early 206 BC, during the Roman conquest of Hispania in the Second Punic War against Carthage.[1] The mutineers had several grievances, including not having received the pay due to them and being under-supplied.[1] The proximate causes of the mutiny had existed for years, but had not been addressed to the soldiers' satisfaction.[1] Matters came to a head after rumors spread that their commanding general, Scipio Africanus, had become gravely ill.[1] But the stories proved to be without foundation; he succeeded in suppressing the mutiny and executed its ringleaders.[2][3][4]

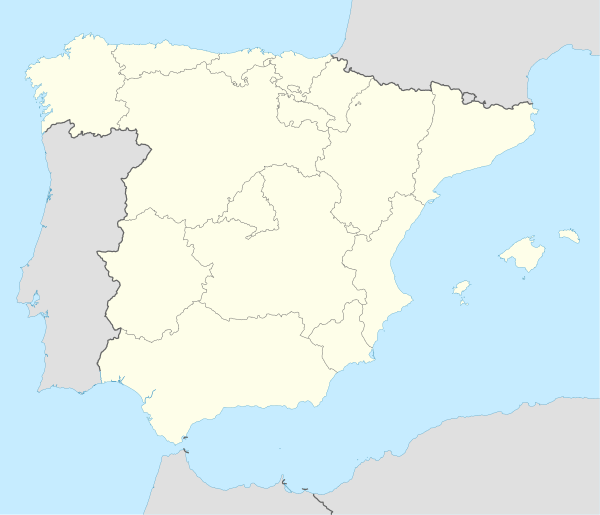

Sucro | |

|---|---|

Sucro Location in Spain | |

| Coordinates: 39°9′50″N 0°15′6″W | |

| Country | |

| Autonomous community | |

| Province | Valencia |

| Comarca | Ribera Baixa |

| Judicial district | Sueca |

| Elevation | 2 m (7 ft) |

| Demonym(s) | Cullerenc, cullerenca Cullerà, cullerana |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Official language(s) | Spanish |

| Website | Official website |

Ancient scholars considered the mutiny to be the most important event of Africanus's early military career.[5]

Location

One source says Sucro is at or near present-day Alzira, a few kilometres east of the mouth of the Sucro/Jucar River.[6] According to another source Sucro is a place half-way between Cartagena and the Ebro River now called Cullera, also near Alzira.[7] Additional sources also verify that it is Cullera.[8][9] Yet another source says it is a place midway between Cartagena and Tarraco.[10] Yet another source says the Sucro camp of 8,000 soldiers was established near the mouth of the Sucro River in a line of communication to New Carthage that Africanus set up, and was just south of Saguntum.[11]

Background

The mutiny happened when Africanus, who had a fortification of some 8,000 militants camped at Sucro, became seriously ill while occupying New Carthage.[10][12] The military revolt broke out because the rumor about Africanus' health eventually became so exaggerated that it was reported that Africanus was either dead or very near death.[13][14] The soldiers at Sucro heard the rumor and planned a mutiny, instigated by some 35 ringleaders who propagated the alleged news.[13] They thought that the great general would not be around much longer.[13] They were frustrated by many aspects of their service and if the revolt turned out successfully, they would then have a chance to voice their concerns.[1]

One of the many items that caused the mutiny was that the soldiers had not been paid in a timely fashion; some had received no pay for years.[15] Another was that they did not receive their share of plunder.[15] Yet another was that they were inadequately supplied with the necessities they needed to properly function.[15] The soldiers were also unhappy about their long periods of inactivity, and wanted either to be sent into battle or back to Rome.[15] They also felt that they had not received proper credit for their part in the campaign to expel the Carthaginians from Hispania.[15] A major issue too was that they had been in service far beyond the term normally required of Roman soldiers.[16]

One of the first things the mutineers did was to show disrespect to their commanding officers.[10] The mutineers then removed the official military tribunes loyal to Rome, and replaced them with their own ringleaders. [13] They proceeded to plunder the towns and areas around the Sucro fort.[17] In addition they removed the normal Roman military insignias and replaced them with the insignia of fasces and axes (a symbol of death).[1]

Development

The mutineers and their ringleaders expected to hear of Africanus's death at any moment, and even anticipated receiving details of his upcoming funeral.[1] Instead, news arrived that Africanus was alive and in good health.[18] Two of the Spanish territory tribe leaders, Indibilis and Mandonius, whom during the beginning of the mutiny broke their alliance with Rome and sided with the mutineers, returned to their frontier territories and took no further part in the mutiny.[18] At this point, the instigators of the rumor of Africanus' death, the ringleaders of the mutiny, claimed that they were just gullible people who had passed on the rumor without having verified it; they feared they might be punished if they were identified as those behind the mutiny.[18] Two of the chief instigators were common soldiers by the names of C. Atrius of Umbria and C. Albius of Cales – "Blackie" and "Whitie" respectively.[18][19] Seven loyal military tribunes at Sucro, that were there already, were very much resented in the camp because they would not be disloyal to Rome and side with the mutineers.[20] They eventually were driven out and went to New Carthage where they were under Africanus's command.[20]

With his 7,000 troops at New Carthage outnumbered by the 8,000 mutineers at Sucro, Africanus decided against summary punishment.[20] Instead, he embarked on a course of action designed to avoid an outright clash.[20] Africanus sent the original loyal seven military tribunes back to Sucro, the same tribunes who had been driven out of the Sucro camp earlier, to discover the reasons for the mutiny.[20][21] They talked calmly to groups of soldiers gathered at the headquarters tent, at meetings, and to individuals.[20] This diplomatic approach helped to reduce tensions.[20] To foster the calm and peaceful mood the tribunes avoided discussing the issue of the soldiers' treasonable behavior.[22] The tribunes then reported their findings to Africanus in New Carthage.[17][18][22]

Solution

Africanus then sent back a letter with the original seven loyal tribunes, asking the mutineers to come to New Carthage to collect the back pay that was owed to them, needed supplies, and other items – as their demands seemed reasonable.[22][23] Meanwhile he sent collectors to the Spanish cities to gather money and supplies.[22] He made a big show of this, so that the soldiers at Sucro would receive reports that Africanus was earnest in his promise of meeting the soldiers' demand in regard to back pay and provisions.[22] He then choose a day for the rebellious soldiers, and their ringleaders, to receive these items.[1][24][25]

Africanus had a secret plan however.[24][25] Part of it was to set up a ruse in which he pretended to march his army against the chiefs Mandonius and Indibilis and the Lacetanians who had played a role in the mutiny and deserted the Roman alliance.[24][25] His troops were to march out of the city on the morning before the mutineers were to receive their back pay at New Carthage.[24][25] The mutineers felt confident then they had the upper hand, since Africanus' army would be gone and only their own Sucro army of some 8,000 troops would be there to confront the pale sick general alone.[26] Africanus instructed his seven loyal tribunes to find out who the ringleaders were;[26] each of the tribunes was to turn in five names.[22] Other officials were then to meet the instigators and attach themselves to the leaders of the Sucro rebellion.[22]

The culprits were greeted with pleasant words and with professional diplomacy when they arrived at New Carthage and were invited to their quarters to be wined and dined into the night.[18][27] Africanus had given the seven loyal tribunes and the Roman guards instructions to arrest the ringleaders once they were in a drunken stupor; they were then placed in leg irons and held in jail.[28]

The next morning Africanus assembled all 8,000 mutinous troops in the public forum market-place; to their amazement Africanus appeared to be robust and in perfect health.[25][29] At this point M. Junius Silanus, a lieutenant of Africanus and second in command, surrounded the unarmed 8,000 mutineers with his armed 7,000 troops that in reality had not left the city at all.[25] Africanus gave a speech in which he scolded the mutineers for their high treason against Rome. The loyal armed soldiers then struck their swords against their metal shields, greatly alarming the unarmed mutineers.[25] They then watched in horror while their bound ringleaders were called by name, stripped to the waist, then brought to the center of the forum, punished and beaten, and tied to a stake and finally beheaded in front of them.[29][30] Their headless bodies were dragged away on the ground.[25] The mutineers were then given their back pay, but only after removing their insignia of fasces and axes.[31] They had to take a new oath of allegiance to Rome and to Africanus and also vow that they would never mutiny again.[32] Thus ended the mutiny at Sucro and regaining of the 8,000 troops by Africanus.[11]

Aftermath

When Africanus returned to Rome in 205 BC he celebrated games (ludi) that he had promised during the mutiny.[33] He dedicated the games to his success in quelling the mutiny at Sucro, rather than for his victories over the Carthaginians in Spain.[33]

Footnotes

- Livy 28.24

- Chrissanthos, p. 183

- Livy 28.24–29

- Polybius 11.25–30

- Chrissanthos, p. 173. Despite a lack of interest on the part of modern historians, the ancients treat the mutiny at Sucro as the most important incident of Scipio's early career.

- Boix, p. 145 Almost buried in a grove of mulberry trees and towering stands a compact mass of buildings that dominate some towers, and utterly old walls. That is the town of Alzira, that's the old Sucro. Not only in geography, but history also has its place in the city of Sucre.

- Florez, p. 34 paragraph 70 Latin translation: But part of the sea coast in Half in a way even to the Spaniard hence the part Sucro has the distance of the river, and its raids, the city and of the same name.

- Murray, p. 498

- Granell, pp. 67–92

- Liddell, p. 72

- Scullard, pp. 100-101

- Chrissanthos, 178

- Chrissanthos, p. 180

- livy 28.24

- Chrissanthos, p. 179

- Sluiter, p. 356

- Polybius 11:25

- Livy 28:25

- Liddel, p. 77

- Chrissanthos, p. 181

- Scullard, p. 148

- Chrissanthos, p. 182

- Appian vi.34

- Polybius 11:26

- Livy 28.26

- Liddell, p. 74

- Appian vi.35

- Polybius 11:30

- Appian vi.36

- JSTOR Chicago Journals (Classical Philology), Vol. 15, No. 2, Apr., 1920, Mutiny in the Roman Army by William Stuart Messer

- Livy 28.27

- Livy 28.28

- Livy 28:39

References

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Primary sources

Secondary sources

- Boix, Vicente, Memoria histórica de la inundacion de la Ribera de Valencia en los dias 4 y 5 de Noviembre de 1864, Imprenta de La Opinion, á cargo de José Domenech, 1865

- Chrissanthos, Stefan G., 'Scipio and the Mutiny at Sucro, 206 B.C.' in Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, Bd. 46, H. 2 (2nd Qtr., 1997), pp. 172–184. [JSTOR subscription required.]

- Flórez, Enrique, España sagrada: Trata de la Provincia Cartaginense..., Volume 5 , Real Academia de la Historia, 1839, Original from the Complutense University of Madrid.

- Granell, John B., Swedish History, from the earliest times to the present, Importing Swedish, 1807

- Liddell Hart, Sir Basil Henry, A greater than Napoleon: Scipio Africanus, Edinburgh ; London : Blackwood, 1927; repr. New York: Biblo & Tannen, 1971, ISBN 0-8196-0269-8

- Murray J., A classical manual: being a mythological, historical, and geographical commentary on Pope's Homer and Dryden's Aeneid of Virgil, 1833

- Sluiter, Ineke, Free speech in classical antiquity, BRILL, 2004, ISBN 90-04-13925-7

- Scullard, H. H., Scipio Africanus: Soldier and Politician (London 1970) 100-1;

Further reading

- Gabriel, Richard A., Scipio Africanus: Rome's greatest general, pp. 132–134, Potomac Books, Inc., 2008, ISBN 1-59797-205-3