Music Hall Strike of 1907

The Music Hall Strike of 1907 was a theatrical dispute which took place between music hall employees, stage artistes and London theatre proprietors. The catalyst for the strikes were the employees' lack of pay, the scrapping of perks, and an increase in working hours, and matinée performances.

The strike commenced on 22 January 1907 at the Holborn Empire in London and lasted for two weeks. The dispute gained momentum owing to the support from popular entertainers including Marie Dainton, Marie Lloyd, Arthur Roberts, Joe Elvin and Gus Elen,[1] all of whom were active on picket lines outside both London and provincial theatres.

The strikes ended two weeks later and resulted in a rise in pay and better working conditions for both stage workers and artistes.[2]

Pre-strike years

Music hall entertainment originated in the plethora of London taverns and coffee houses of 18th century. The atmosphere within the venues appealed mainly to working class men[3] who ate, drank alcohol and initiated illicit business deals together. They were entertained by performers who sang songs whilst the audience socialised. By the 1830s publicans designated specific rooms for patrons to go where they formed musical groups. The meetings culminated in a Saturday evening presentation of the week's rehearsals. The meetings became popular and increased in number to two or three times a week.[4]

Music hall entertainment received its first surge in popularity during the 1860s[5] the audiences of which consisted of mainly working class people.[3] The impresario Charles Morton actively invited women into his music hall, believing that they had a "civilising influence on the men".[4] The surge in popularity further attracted female performers and by the 1860s, it had become common place for women to appear in the halls.[4]

By 1875 there were 375 music halls in London[4] with a further 384 in the rest of England. In-line with the increased number of venues, proprietors enlisted a catering workforce who would supply food and alcohol to patrons. In London, and to capitalise on the increasing public demand, some entertainers frequently appeared at several halls each night. As a result, the performers became popular, not only in London, but in the English provinces.[5]

Preceding years and factors

To match the success of the modern layout of contemporary theatres, music hall proprietors began to adopt the same design. One such establishment, the London Pavilion, was restyled as such in 1885. The refurbishments, which included fixed seating in the stalls, lead to the early origins of variety theatre, but the improvements proved expensive and managers had to adhere to the strict safety regulations which had recently been introduced. Together with the increase of the performers fee, music hall proprietors were forced to sell their shares and formed syndicates with wealthy investors.[5]

By the 1890s, music hall entertainment had earned a more risqué reputation. Artists including Marie Lloyd were receiving frequent criticism from theatre reviewers and influential feminists, who disagreed with the bawdy performances. The writer and feminist Laura Ormiston Chant, who was a member of the Social Purity Alliance, disliked the innuendo displayed in music hall performances, and opined that the humour was attractive to nobody other than prostitutes who were beginning to sell their business in auditoriums.[6][7]

In 1895 Chant provided evidence to the London County Council who agreed that the humour was too risqué. They decided to imposed restrictions on the halls including the issuing of liquor licences. Unsatisfied, Chant further attempted to censor the halls by successfully convincing the council to erect large screens around the promenade at the Empire Theatre in Leicester Square, as part of the licensing conditions;[6][7] the screens proved unpopular and were later pulled down by the protesting audiences.[8][9]

In 1898 Oswald Stoll had become the Managing Director of Moss Empires, a theatre chain led by Edward Moss. Between those years, Moss Empires had bought up many of the English music halls and had begun to dominate the business.[5] Stoll became notorious among his employees for implementing a strict working atmosphere. He paid them a little wage and erected signs backstage prohibiting performers and stagehands from using coarse language.[10]

By the start of the 1900s music hall artistes had been in an unofficial dispute with theatre managers over the poor working conditions. Other factors included the poor pay, lack of perks, and a dramatic increase in the number of matinée performances.[11] By 1903 audience numbers had fallen which was attributed in part to the banning of alcohol in auditoriums and the introduction of the more popular variety show format, favoured by Stoll. Profits for the music hall proprietors who had not sold to Moss Empires years earlier had fallen and so an expansion of their syndicate members was formed to control the outgoing expenditures.[12]

The strike

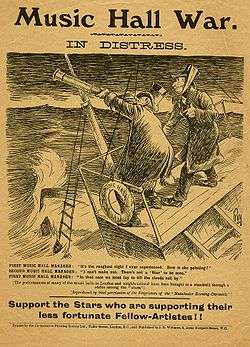

The first significant rift came in 1906,[11] when the Variety Artistes' Federation initiated a brief strike on behalf of its members.[13] Tensions between employees and management had by then grown to such a level that the strike was advocated enthusiastically by the main spokesmen for the trade union and Labour movement – Ben Tillett and Keir Hardie. Picket lines were organised into shifts outside theatres by workers and artistes. The news reached provincial theatres and managers attempted to convince their artistes to sign a contract promising never to join a trade union.[14] The following year, the federation fought for more freedom and better working conditions on behalf of music-hall performers.[15]

On 21 January 1907, the dispute between artists, stage hands and managers of the Holborn Empire had worsened, and workers called for strike action. In support, theatrical workers followed suit and initiated widespread strikes across London.[16] The disputes were funded by wealthy performers including Marie Lloyd.[17][18] To raise spirits, Lloyd frequently performed on picket lines for free and took part in fundraising activities at among others the Scala Theatre in London, for which she donated her entire fee to the fund.[19] Lloyd explained her advocacy: "We the stars can dictate our own terms. We are fighting not for ourselves, but for the poorer members of the profession, earning thirty shillings to £3 a week. For this they have to do double turns, and now matinées have been added as well. These poor things have been compelled to submit to unfair terms of employment, and I mean to back up the federation in whatever steps are taken."[20][21]

Resolutions

The strike lasted for almost two weeks ending in arbitration, which satisfied most of the main demands, including a minimum wage and a maximum working week for performers.[2]

References

- "Music Hall War", Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser, 5 February 1907, p. 8

- "Music Hall War Ended", Hull Daily Mail, 9 November 1907, p. 4

- Davis & Emeljanow, p. x.

- "The Story of Music Hall", Victoria and Albert Museum, accessed 5 June 2014.

- "A Brief History of the Music Hall", Windyridge Music Hall CDs, accessed 5 June 2014.

- Farson, p. 64

- "Sources for the history of London Theatres and Music Halls at London Metropolitan Archives" Archived 2013-09-05 at the Wayback Machine, London Metropolitan Archives, Information Leaflet Number 47, pp. 4–5, accessed 11 April 2013

- Gillies, p. 315

- Gillies, p. 89

- "Victorian Theatre: Oswald Stoll", Victoria and Albert Museum, accessed 5 June 2014

- Pope, p. 131

- Kift, p. 33

- Gillies, p. 171

- "Music Hall War To Be Carried into Provinces", Dundee Courier, 31 January 1907, p. 4.

- Pope, pp. 131–132

- "The Music Hall War", Hull Daily Mail, 25 January 1907, p. 3

- Farson, p. 83

- Pope, p. 132

- Pope, p. 133

- "Strike of the month: Marie Lloyd and the music hall strike of 1907" Archived 2011-07-08 at the Wayback Machine (Tribune magazine) 22 September 2007, accessed 25 November 2007

- Gillies Midge Marie Lloyd, the one and only (Gollancz, London, 1999)

Sources

- Davis, Jim; Emeljanow, Victor (2001). Reflecting the Audience: London Theatregoing, 1840–1880. Iowa: University of Iowa Press. ISBN 978-1-902806-18-1.

- Farson, Daniel (1972). Marie Lloyd and Music Hall. London: Tom Stacey Ltd. ISBN 978-0-85468-082-5.

- Gillies, Midge (1999). Marie Lloyd: The One And Only. London: Orion BooksLtd. ISBN 978-0-7528-4363-6.

- Kift, Dagmar (1996). The Victorian Music Hall: Culture, Class and Conflict. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-47472-6.

- Macqueen-Pope, Walter (2010). Queen of the Music Halls: Being the Dramatized Story of Marie Lloyd. London: Nabu Press. ISBN 978-1-171-60562-1.