Mugdock Castle

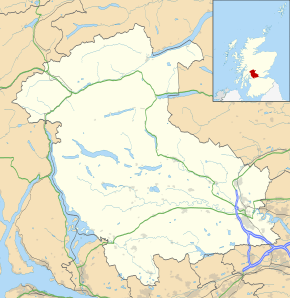

Mugdock Castle was the stronghold of the Clan Graham from the middle of the 13th century. Its ruins are located in Mugdock Country Park, just west of the village of Mugdock in the parish of Strathblane. The castle is within the registration county of Stirlingshire, although it is only 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) north of Milngavie, East Dunbartonshire, on the northern outskirts of Greater Glasgow.

| Mugdock Castle | |

|---|---|

| Strathblane, Scotland NS550772 | |

The south facade of Mugdock Castle, with the single remaining tower | |

Mugdock Castle | |

| Coordinates | 55.965556°N 4.324444°W |

| Type | Courtyard castle |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Stirling Council |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Condition | Ruined |

| Site history | |

| Built | 14th century |

| Built by | David de Graham? |

| In use | Until mid-17th century |

| Materials | Stone |

| Demolished | Slighted 1641 |

History

The lands of Mugdock were a property of the Grahams from the mid-13th century, when David de Graham of Dundaff acquired them from the Earl of Lennox. It is possible that the castle was built by his descendant, Sir David de Graham (d. 1376),[1] or by his son in 1372.[2] In 1458, the lands were erected into the Barony of Mugdock. Later, in 1505, the Grahams were created Earls of Montrose.

The most famous of the Montrose Grahams, James Graham, 1st Marquess of Montrose, may have been born at Mugdock Castle in 1612.[3] During the Bishops' Wars, a prelude to the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, Montrose briefly supported the Covenanters. He was imprisoned in Edinburgh in 1641 for intrigues against Archibald Campbell, 1st Marquess of Argyll, who was to become his arch-enemy. While Montrose was in prison, Lord Sinclair sacked Mugdock. Montrose returned there, however, until 1644 when he began his Royalist revolt, becoming the King's commander in Scotland. Mugdock was sacked again that year. Following the defeat of Charles I, Montrose was executed in 1650, and the lands were forfeited to the Marquess of Argyll. In 1661 Argyll too was executed, and Mugdock was returned to the Grahams, who restored the castle over a two-year period, building a mansion within the old castle walls.[4] In 1682 the Grahams bought Buchanan Auld House near Drymen, a dwelling more fitting the title of "Marquess", though the family's official seat was kept at Mugdock Castle for a some time.

A terraced walled garden, incorporating a summer house, was built to the east of the castle in the 1820s. Local historian John Guthrie Smith (1834–1894), a relative of the Smith family of nearby Craigend Castle, leased the house from 1874.[2] He had the 17th-century mansion demolished, and commissioned a Scottish baronial style house to be built in the ruins of the old castle.[5] It was designed by architects Cambell Douglas & Sellars, and was extended to designs by James Sellars in the 1880s.[6]

During World War II the house was requisitioned for use by the government. In 1945, Hugh Fraser (later Lord Fraser), owner of the large retail chain now known as House of Fraser, purchased Mugdock Castle from the Duke of Montrose.[7] The 19th-century Mugdock House burned down in 1966, along with the remaining 16th-century outbuildings.[5] In 1981 Lord Fraser's son Sir Hugh Fraser, 2nd Baronet, gifted the castle and the surrounding estate to Central Regional Council for use as a country park.[2] The estate remains as Mugdock Country Park, and the ruins are publicly accessible. The remaining tower of the 14th-century castle has been renovated as a museum. The castle is protected as a scheduled monument.[8]

Architecture

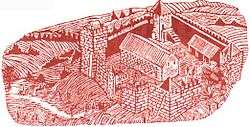

The early castle

The original castle was built in the mid-14th century. It may have been shield-shaped on plan, comprising towers arranged around a courtyard, and linked by curtain walls and ranges of buildings.[1] In the middle of the south wall was the main gate. The castle stood on a natural, steep-sided mound formed of hard volcanic rock, at the west edge of Mugdock Loch, which was larger than its present extent.[9] Of the early castle, only the south-west tower remains complete, and forms the most recognisable feature of the ruins. The narrow tower is of four storeys, with an entrance on the first floor, accessed via exterior steps on the east side. Inside the basement is vaulted, and a single room occupies each storey. On the outside, a line of corbels projects the two upper storeys out from the lower levels, giving the tower a distinctive "top-heavy" appearance. The only other remains are the basement of the north-west tower, part of the gatehouse, and linking sections of curtain wall.

Expansion

The castle was extended in the mid-15th century, probably around the time that the barony was created. An outer wall was built to enclose the majority of the mound as an outer courtyard. This courtyard had its main entrance to the south, adjacent to the south-west tower. Inside the courtyard are the ruins of various stone buildings, mainly dating from the 16th century. These include a chapel at the north extent of the courtyard, and a domestic range at the south-west. Much of the outer curtain wall has also disappeared, although the southern section remains.[5]

The Victorian house

By the late 19th century, much of the castle was in ruins. When the antiquarian John Guthrie Smith (son of William Smith of Carbeth Guthrie)[10] built his mansion, any remains of the eastern towers were obliterated. The one surviving tower was incorporated into the new building, via a first-floor covered passage, over a wide-arched bridge. The house itself was L-shaped and three storeys high, and built in the Scottish baronial style. The front door faced the south-west tower, framing a small courtyard. The house was mostly demolished to the foundations in 1967, although some walls stand to first-floor level.

References

- Fawcett, p.18

- "Mugdock Castle Timeline". Mugdock Country Park. Archived from the original on 29 March 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- Coventry, p.327

- Gazetteer for Scotland

- "Mugdock Castle, general". Canmore. Historic Environment Scotland. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- "Mugdock House". Dictionary of Scottish Architects. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- "Famous Residents". Mugdock Country Park. Archived from the original on 29 March 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- Historic Environment Scotland. "Mugdock Castle,Milngavie (SM2805)". Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- Lindsay, p.386

- http://www.clanmacfarlanegenealogy.info/genealogy/TNGWebsite/getperson.php?personID=I38335&tree=CC

- Coventry, Martin The Castles of Scotland (3rd Edition), Goblinshead, 2001

- Fawcett, Richard (1994). Scottish Architecture from the Accession of the Stuarts to the Reformation 1371–1560. The Architectural History of Scotland. Edinburgh University Press.

- Lindsay, Maurice The Castles of Scotland, Constable & Co. 1986

- Mason, Gordon The Castles of Glasgow and the Clyde, Goblinshead, 2000