Motyxia

Motyxia is a genus of cyanide-producing millipedes (collectively known as Sierra luminous millipedes or motyxias[1]) that are endemic to the southern Sierra Nevada, Tehachapi, and Santa Monica mountain ranges of California. Motyxias are blind and produce the poison cyanide, like all members of the Polydesmida. All species have the ability to glow brightly: some of the few known instances of bioluminescence in millipedes.

| Motyxia | |

|---|---|

| |

| A replica Motyxia at the American Museum of Natural History | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Subphylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Motyxia Chamberlin, 1941 |

| Type species | |

| Motyxia kerna Chamberlin, 1941 | |

| Species | |

|

M. bistipita | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Amplocheir Chamberlin, 1949 | |

Description

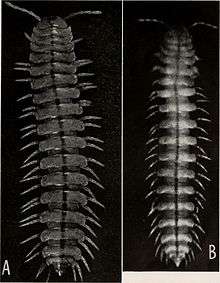

Adult Motyxia reach 3 to 4 cm in length, 4.5 to 8 mm wide, with 20 body segments, excluding the head. Females are slightly larger than males. Like other polydesmidans ("flat-backed" millipedes) they lack eyes and have prominent paranota (lateral keels). They are typically tan to orange-pink in color (except M. pior), with a dark mid-dorsal line. M. pior is the most variable in color, and ranges from dark gray to greenish-yellow to bright orange. They lack bumps on the metatergites (the dorsal plates possessing paranota), giving a somewhat smooth appearance.[2] The anterior 2-3 diplosegments are oriented cephalically (towards the head), a trait most distinct in M. sequoiae, nearly indistinct in Motyxia porrecta. They are fluorescent under black light (millipedes in the tribe Xystocheirini display some of the brightest fluorescence of the U.S. Xystodesmidae species). Most uniquely they are bioluminescent: emitting light of their own production.[1]

Bioluminescence

The 9 species and 11 subspecies of Motyxia are some of the few known bioluminescent species of millipedes, a class of about 12,000 known species.[3] Motyxia sequoiae glows the brightest and Motyxia pior the dimmest.[4] Light is emitted from the exoskeleton of the millipede continuously, with peak wavelength of 495 nm (the light intensifies when the millipede is handled).[5] Emission of light is uniform across the exoskeleton, and all the appendages (legs, antennae) and body rings emit light. The internal organs and viscera do not emit light. Luminescence is generated by a biochemical process in the millipede's exoskeleton.[5] The light originates by way of a photoprotein, which differs from the photogenic molecule luciferase in firefly beetles.[6]

Motyxia's photoprotein contains a porphyrin and is about 104 kDa in size.[6][7] However, the structure of the luminescent photoprotein remains uncertain, and its homology to molecules of closely related arthropods is unknown.

Scientists familiar with Motyxia were at odds over the function of bioluminescence in Motyxia. Various functions were suggested: a nighttime aposematic warning signal, that it had no function at all, or that it inadvertently attracted predators.[1][8] A field study tested the hypothesis that luminescence acts as a warning signal. Based on the results of the field experiment conducted in California, in a spot where Motyxia are native, researchers found that luminescence strongly deterred nocturnal mammalian predators: live Motyxia with their luminescence obscured by paint suffered higher attack rates, and clay models with luminescent paint had fewer attacks than unpainted models.[4][9]

Xystocheir bistipita was renamed to Motyxia bistipita after it was discovered it glowed in a lab experiment. M. bistipita lives in low elevations of the Sierra Nevada mountains in California, in a hotter, drier climate than other Motyxia. The glow is believed to be a response to heat; the bioluminescent proteins help neutralize the body's byproducts caused by heat. The bioluminescence later evolved as a warning signal to predators that the body contained cyanide.[10][11]

Besides Motyxia, the only known bioluminecscent millipedes are Paraspirobolus lucifugus (Spirobolellidae), from Japan and Taiwan, and Salpidobolus (Rhinocricidae), both in the order Spirobolida.[12] Another luminescent species of dubious existence from North America has been claimed, but it has not been found since the 1890s and the luminescence attributed to it is believed to have been larval phengodid beetles, also known as glowworms.[1]

Ecology and behavior

Motyxias occur in live oak and giant sequoia forests, and notably also in meadows. The presence of xystodesmid millipedes in meadows is atypical for the family. Most species are observed under canopies of broad-leaf deciduous forests. All Motyxia species are exclusively nocturnal. During the day, individuals are burrowed beneath the soil. At night, they emerge (by an unknown mechanism not related to light since they're blind) and feed on decaying vegetation. Individuals of the species M. sequoiae have been observed climbing on tree trunks, possibly consuming algae and lichens adhering to the bark.

Natural predators of motyxias include rodents,[4] geophilid centipedes, and larval phengodid beetles.[1]

Life cycle

The life cycle of M. sequoiae was studied in detail in the early 1950s.[2] Eggs are round, about 0.7mm in diameter, and are laid in masses of 70-160 eggs. After about two weeks the larvae hatch with seven body segments and three pairs of legs, and measure about 1.7mm long. Juveniles exhibit bioluminescence as early as hatching. Additional legs and body segments develop with each molt, during which the animals construct a protective spherical cocoon or molt chamber out of soil. Larvae go through seven developmental stages (instars) before reaching adulthood. In males, the single pair of reproductive structures (gonopods) begin to develop in the 4th instar, before which male and females have equal numbers of walking legs, and after which males have one fewer pair.[2]

Distribution

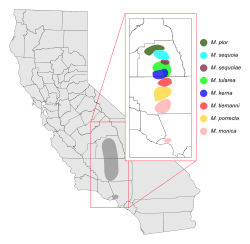

Motyxia species occur in an approximate 280 km (175 mi) vertical range across three counties in California: Los Angeles, Kern and Tulare counties.[1] Species predominately occur in the Santa Monica, Tehachapi, and southern Sierra Nevada Mountains. The northernmost species is M. pior, which occurs as far north as Crystal Cave in Sequoia National Park. The southernmost species is M. monica, which has a disjunct distribution: a population in southern Kern County, and an isolated one in the Santa Monica Mountains near the city of Los Angeles. The range of the eight species largely do not overlap, although M. tularea overlaps with M. kerna and M. sequoiae.[8]

Species

List of Species[13]

| Species | Taxon author | Geographic range[8] | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| M. bistipita | (Shelley, 1996) | Low elevations of the Sierra Nevada mountains in California | Originally described as Xystocheir bistipita |

| M. kerna | Chamberlin, 1941 | Southern Tulare Co. to northern Kern Co., | |

| M. monica | Chamberlin, 1944 | Kern Co., south of the Kern River, and a disjunct population in the Santa Monica Mountains. | |

| M. pior | Chamberlin 1941 | Tulare Co., Sequoia National Park | |

| M. porrecta | Causey & Tiemann, 1969 | Kern River Valley | |

| M. sequoia[lower-alpha 1] | (Chamberlin, 1941) | East Fork of the Kaweah River, Tulare Co. | Originally described as Xystocheir sequoia. Two subspecies or races: M. s. sequoia and M. s. alia. |

| M. sequoiae[lower-alpha 1] | (Loomis & Davenport, 1951) | Headwaters of the Tule River (Middle fork), Tulare Co. | Originally described as Luminodesmus sequoiae. |

| M. tiemanni | Causey, 1960 | Northern Kern Co. | |

| M. tularea | (Chamberlin, 1949) | Central Tulare Co. to extreme northern Kern Co. | Originally described as Xystocheir tularea. Two subspecies: M. t. tularea. and M. t. ollae. |

Classification and evolution

The speciation of Motyxia is believed to have been driven by geological events and a drying climate following the most recent Pleistocene glaciation, while reproductive isolating mechanisms include rivers which are at their fullest levels in times when adults are most active, and marked differences in rainfall and suitable habitat across mountainous terrain.[1]

Motyxia is a member of the family Xystodesmidae, a group of large and colorful millipedes, and M. monica is the southernmost species of Xystodesmidae in western North America.[1] Within Xystodesmidae, Motyxia is placed in the tribe Xystocheirini along with the genera Anombrocheir, Parcipromus, Wamokia, and Xystocheir, all of which are native to California.[14]

Notes

- The near identical spelling of M. sequoia and M. sequoiae are due to both species originally being named under different genera. Under the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature the names cannot be replaced.[1]

References

- N.B. Causey & D.L. Tiemann (1969). "A revision of the bioluminescent millipedes of the genus Motyxia (Xystodesmidae: Polydesmida)". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Academy. 113: 14–33.

- Davenport, D., Wootton, D. M., & Cushing, J. E. (1952). "The biology of the Sierra luminous millipede, Luminodesmus sequoiae". The Biological Bulletin. 102 (2): 100–110. doi:10.2307/1538698. JSTOR 1538698.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- P. Sierwald & J.E. Bond (2007). "Current status of the myriapod class Diplopoda (millipedes): Taxonomic diversity and phylogeny". Annual Review of Entomology. 52: 401–420. doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.52.111805.090210. PMID 17163800.

- P.E. Marek; D.R. Papaj; J. Yeager; S. Molina; W. Moore (2011). "Bioluminescent aposematism in millipedes". Current Biology. 21 (18): R680–R681. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2011.08.012. PMC 3221455. PMID 21959150.

- J.W. Hastings & D. Davenport (1957). "The luminescence of the millipede Luminodesmus sequoiae". Biological Bulletin. 113 (1): 120–128. doi:10.2307/1538806. JSTOR 1538806.

- O. Shimomura (1984). "Porphyrin chromophore in Luminodesmus photoprotein". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology B. 79 (4): 565–567. doi:10.1016/0305-0491(84)90367-5.

- V.R. Viviani (2002). "The origin, diversity, and structure function relationships of insect luciferases". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 59 (11): 1833–1850. doi:10.1007/PL00012509. PMID 12530517.

- R.M. Shelley (1997). "A re-evaluation of the milliped genus Motyxia Chamberlin, with a re-diagnosis of the tribe Xystocheirini and remarks on the bioluminescence (Polydesmida: Xystodesmidae)". Insecta Mundi. 11: 331–351.

- "If you see a glowing millipede, best not to bite it – Phenomena". Retrieved 2015-05-09.

- nationalgeographic.com 2015-05-04 New Glowing Millipede Found; Shows How Bioluminescence Evolved

- Marek, Paul E.; Moore, Wendy (2015). "Discovery of a glowing millipede in California and the gradual evolution of bioluminescence in Diplopoda". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 112 (20): 6419–6424. doi:10.1073/pnas.1500014112. PMC 4443369. PMID 25941389.

- Oba, Yuichi; Branham, Marc A.; Fukatsu, Takema (2011). "The Terrestrial Bioluminescent Animals of Japan". Zoological Science. 28 (11): 771–789. doi:10.2108/zsj.28.771. PMID 22035300.

- Shelley, Rowland M. (2002). "Annotated Checklist Of The Millipeds Of California (Arthropoda: Diplopoda)". Monographs of the Western North American Naturalist. 1 (1): 90–115. doi:10.3398/1545-0228-1.1.90.

- Hoffman, R. L. (1999). "Checklist of the millipeds of North and Middle America". Virginia Museum of Natural History Special Publications. 8: 359.

Further reading

- J. Rosenberg; V.B. Meyer-Rochow (2009). "Luminescent myriapoda: a brief review". In V.B. Meyer-Rochow (ed.). Bioluminescence in Focus: A Collection of Illuminating Essays. pp. 139–147. ISBN 978-81-308-0357-9.