Moscow Orphanage

The Moscow Orphanage or Foundling Home (Russian: Воспитательный дом в Москве) was an ambitious project conceived by Catherine the Great and Ivan Betskoy, in the early 1760s. This idealistic experiment of the Age of Enlightenment was intended to manufacture "ideal citizens" for the Russian state by bringing up thousands of abandoned children to a very high standard of refinement, cultivation, and professional qualifications. Despite more than adequate staffing and financing, the Orphanage was plagued by high infant mortality and ultimately failed as a social institution.

The main building, one of the earliest and largest Neoclassical structures in the city, occupies a large portion of Moskvoretskaya Embankment between the Kremlin and Yauza River, boasting a 379-metre frontage on Moskva River. The complex was built in three stages over two centuries, from Karl Blank's master plan (1767) to its complete implementation in the 1940s. Today, the ensemble of the Orphanage houses the Academy of Missile Forces and Russian Academy of Medicine.

Architecture

An outgrowth of the Russian Enlightenment, the idea of a state-run orphanage in Moscow was proposed by educator Ivan Betskoy and endorsed by Catherine II of Russia on September 1, 1763. Betskoy envisaged a spacious, strictly controlled, state-of-the-art institution that could raise abandoned infants and train them depending on each child's abilities—in craftsmanship, fine arts, or in preparation for university classes. Children born in slavery were automatically emancipated, and upon graduation could join the state service or the merchant estate.

The institution was set on a large lot of land between Kitai-gorod, Solyanka Street, Moskva and Yauza rivers, site of a former armoury. Construction was financed through a public subscription. The Empress herself pledged 100,000 roubles; the largest private donations, from Prokofy Demidov and Ivan Betskoy, amounted to 200,000 and 162,995 roubles.[1]

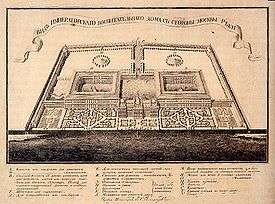

According to the master plan by Karl Blank (assisted by Yury Felten), the Orphanage was designed as a chain of three square-shaped buildings: the eastern wing for the girls, the western wing for the boys and the central administration block connecting them. The inauguration ceremony, attended by the Empress, was held on April 21, 1764, although the western wing was not completed by Blank until three years later. The central building, constructed between 1771 and 1781, was surmounted by a square dome with a spire. The adjacent Moskva River embankment was paved in 1795–97 and set in granite in 1801–06.

Although the eastern wing did not materialize, the Orphanage expanded continuously, under the supervision of senior architects Giovanni Gilardi (1790s-1817) and Domenico Gilardi (1817–34). Domenico and Afanasy Grigoriev designed and built the Board of Trustees building facing Solyanka Street. By the mid-19th century, the Orphanage had evolved into "a city within a city" – a largely independent and wealthy institution housing thousands of residents. The bulk of the Orphanage survived the Fire of 1812 and preserved its original aspect until the mid-20th century. In the 1940s, the missing eastern wing was finally constructed to a design by Alexander Loveyko, who generally followed Blank's original plans, albeit in a considerably simplified form.

Early years (1764–1797)

On the inauguration day, 19 newborn babies were brought to the unfinished Orphanage. Two of them were publicly baptized Catherine and Paul, after the Empress and her heir, but both died soon afterward. This was an early portent of extremely high infant mortality that would be characteristic of the Orphanage in the 18th century.

Of some 40,996 children admitted to the Orphanage during Catherine II's reign, 35,309, or 87%, died during their stay there.[1] As a result, the vast complex housed only a handful of survivors. A 1792 report listed as few as 257 resident orphans who studied a variety of trades ranging from metallurgy to accountancy.[1] Several attempts to decrease mortality by passing infants on to foster families did not improve the survival rate. The aged Betskoy could not be relied on for managing the expanding faculty, and the Orphanage became notorious for fraud and child abuse.[2]

Children lived at the Orphanage until the age of 11, whereupon they were sent for training to local factories and government offices. Some were assigned to the Michael Maddox theater school; others managed to qualify for free admission to Moscow State University. 180 students furthered their education in the universities of Western Europe. The majority, however, graduated with little more than a rouble in cash and a passport (which served to distinguish free men from serfs).

The institution was managed by the Board of Trustees and financed by private donations and two special taxes—a tax on public theater shows and a tax on playing cards. For nearly a century, all playing cards sold in Imperial Russia were taxed 5 kopecks per deck on domestic-made cards and 10 kopecks on imports. As a result, every pack of Russian cards displayed the symbol of the Orphanage, the pelican. This tax generated 21,000 roubles in 1796 and 140,000 roubles by 1803.

Beginning in 1772, the Orphanage also managed three banks: Loan Treasury, Savings Treasury, and Widows Treasury. These financial institutions, initially plagued by fraud and poor management, became effective and influential under the guidance of Empress Maria. By 1828, their total assets exceeded 359 million roubles, the largest capital assets in all of Moscow.[3] This stock was the principal source of cash for the Orphanage throughout the 19th century.

Orphanage Theatre

In 1772, plans began to be formed for a "domestic theatre" affiliated with the Foundling Home. There were classes on acting, and the first production premiered late in 1773. In the course of 1778 alone, the Orphanage Theatre produced twelve comedies, two operas, and several ballets. By October 1783, the troupe of orphans had become so popular that Baron Vanzura petitioned the Empress to open this "home theatre" for the general public. Catherine readily approved the project of a public theatre and presented to the Orphanage a disused wooden building of the Golovin Opera House near the Yauza. The public Orphanage Theatre was inaugurated on 9 February 1764 with the pantomime The Marine Brigands and the ballet Venus and Adonis.

The creation of a rival theatre company enraged Michael Maddox, an English entrepreneur who held the monopoly on public entertainment in Moscow. Under his pressure, the Board of Trustees agreed to close the Orphanage Theatre in November 1784, but the orphans were allowed to continue their acting careers on the stage of the Petrovsky Theatre, which was run by Maddox.

Reforms of Empress Maria (1797–1828)

In May 1797 Emperor Paul of Russia asked his wife, Maria Feodorovna, to oversee the national charities. Empress Maria remained in charge of the Orphanage and similar institutions after her husband's assassination in 1801 until her death in 1828.

Step by step, Empress Maria changed the social profile of the Orphanage. She encouraged a thorough inspection of prospective foster parents and limited admissions "from the street", measures which decreased the inflow of new orphans and considerably reduced mortality. By 1826, the mortality rate was reduced to 15% per annum,[3] a figure outrageous by modern standards but a great improvement on the 18th century.

The institution, headed by retired general Ivan Tutolmin, wasn't damaged during Napoleon I's occupation of Moscow, despite its proximity to the centre of the Fire of Moscow, which completely destroyed the adjacent districts, including Kitai-gorod and Taganka. While the French held the city, the Orphanage provided shelter for 350 children and an unspecified number of wounded soldiers. After the end of the Napoleonic wars, the Board of Trustees capitalized on the recent disaster by building cheap rental housing on its properties. As a result of this policy, the new facilities housed up to 8,000 residents of all ranks in the 1820s.[4]

Empress Maria realized the need to downsize the institution, separating children from adult tenants and improving the educational program for the former. She detested the "dirty" appearance of trade workshops and transferred the younger inhabitants to new, independent orphanages. The Moscow Crafts College, the largest spin-off, was established as an orphanage for teenagers in 1830, and continues today as the Bauman Moscow State Technical University.[4] In the old Orphanage, a premium was placed upon high-level educational programs along the lines of the "Latin classes" for boys (established 1807) and the "midwife classes" for girls.

By the 1830s, the Orphanage finally achieved the espoused aim of taking the ablest children from the streets and preparing them for state service and professional careers. Among the teachers and tenants were Gerhardt Friedrich Müller, Alexander Vostokov, Sergey Solovyov, Vasily Klyuchevsky, Nicholas Benois, Isaak Levitan, and Vasily Vereshchagin. Until the Russian Revolution of 1917, the Moscow Orphanage ranked among the most prominent national charities.

20th century

The Bolsheviks disbanded the Orphanage immediately after the Revolution. The main building was conveyed to the Soviet trade unions, followed by Dzerzhinsky Military Academy and a long succession of state institutions. The satirical novel The Twelve Chairs features a famous episode: an abandoned wife chasing Ostap Bender, her runaway husband, through numerous editorial offices of the former Orphanage.

During Joseph Stalin's reconstruction of old Moscow (1937), several Orphanage buildings facing Bolshoy Ustinsky Bridge were torn down to make way for the new bridge. The right wing of the Orphanage was topped out by June 1941, but the project was not completed until after World War II. Viewed from the outside, this later addition is only marginally different from the left wing, to which the top floor was added at about the same time. The main building conforms quite closely to Blank's original designs.

21st century – Parliament Center

Moscow chief architect A. Kuzminov proposed to house Russian Parliament Center in the premises of the Orphanage. The Russian Parliament Center will be used by both Russian Senate and Russian State Duma as their main residence.[5]

See also

- Smolny Institute – another educational institution founded by Betskoy

- Neoclassical architecture in Russia

- The Italian (2005 film)

References

- (in Russian) I. L. Volkevich, History of Moscow Technical University, ch.2

- (in Russian) Alexandra Veselova, Betskoy's Concept

- (in Russian) Volkevich, ch.3

- (in Russian) Volkevich, ch.4

- Rossiiskaya Gazeta