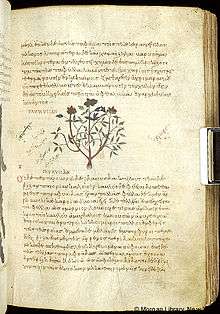

Morgan Dioscurides

The Morgan Dioscurides (Pierpont Morgan Library, MS M. 652) is a 10th-century Byzantine illuminated copy of the De Materia Medica by the Greek physician Dioscurides, which covers the medical use of herbs and other natural resources. It is a tenth-century incarnation of Dioscorides’ De Materia Medica, written in AD 65 and widely regarded as the most comprehensive collection of naturally occurring resources (plants, animals etc.) and their medical uses. Today, it is regarded as an early, fairly accurate, form of pharmacological text,[1] in herbal form.

History and Context in Byzantium

The Morgan Dioscurides was written in Greek and illustrated in Constantinople, the capital of the Greek-speaking Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire, around the tenth century AD.[2] Constantinople, often called the “New Rome”, had a culture that was heavily inspired by Greco-Roman art and architecture. This adherence to classical Greco-Roman law and religion made for a peaceable, organized political structure. As such, as Oswei Tempkin states in his journal article "Byzantine Medicine: Tradition and Empiricism", "Medicine of the period of Constantinople was Christian. It accepted rather than shaped a tradition". Medical thinking during this time reflected religious philosophy, seeking to utilize God's creation.[3] This is evident in works like De Materia Medica. Within this religious and classical structure, the elite could easily utilize Roman law to establish and maintain power dynamics. The most powerful were those in charge of urban centers of heightened economic activity. As an essential port of trade between east and west, the nation also had the capability to borrow from multiple cultures and utilized this access to create gilded, masterful, artistic pieces. This period was followed by a shift from prevalence of sculpture in the round to low relief sculpture and two-dimensional art. During this time, Byzantium’s standing as a wealthy trading nation factored into their art production as imported mosaics were crafted into mosaic artworks.[4]

Appearance and Contents

Bound in lozenge-patterned dark brown leather over heavy boards around the 14th century, the manuscript includes about 769 illustrations on 385 leaves (or pages). It contains an alphabetical, five book version of De Materia Medica, with sections on “Roots and Herbs”, “Animals, Parts of Animals and Products from Living Creatures”, “Trees”, “Wines and Minerals, etc.” “On the Power of Strong Drugs to Help or Harm”, “On Poisons and their Effect” “On the Cure of Efficacious Poisons”, “A Mithridatic Antidote”, “Anonymous Poem on the Powers of Herbs”, Eutecnius’ “Paraphrase of the Theriaca or Nicander, and an incomplete paraphrase of the Haliutica of Oppianos. Its owners have added their own content to its pages - most notably by an Arabic-speaking individual who, in the 15th century, added inscriptions in Arabic and genitalia to some animals.[5] Its pages are gouache on vellum, it is written in one column with about 30 lines per page, and it is 15 1/2 x 11 13/16 inches in height and width (395 x 300 mm).[6] About 50 illustrations are missing from the original text.[7]

Comparable Works

The illustrations closely reflect those in the Vienna Dioscurides. Many of the illustrations in the Morgan Dioscurides resemble those in the Juliana Anicia Codex, produced in the year 512. The 6th century text Codex Neapolitanus may have been a source in the production of the Morgan Dioscurides as it contains several images that appear in the Morgan Dioscurides that are not present in other works like the Julianna Anicia Codex.[8]

Ownership

After its creation in Byzantine Constantinople the Morgan Dioscurides changed hands many times. Following a stint in the 15th century with an Arabic-speaking owner, who made marginal comments, the work was moved back to Constantinople in the 16th century and was listed in the library of the Greek scholar Manuel Eugenicos. It was then owned by Domenico Sestini in Italy c.1820. It was in the collection of Marchese C. Rinucchi of Florence from 1820-1849 after which it most probably circulated around England with the booksellers John Thomas Payne and Henry Floss from 1849-1857. On April 30, 1857, it was sold at the Payne Sale to Charles Phillips for Sir Thomas Phillipps. In 1920, it was purchase by J.P. Morgan Jr. from the Phillips’ estate.[9]

Notes

- Hummer,Kim. “Rubus Iconography: Antiquity to the Renaissance”. Purdue: Accessed September 25, 2013.http://www.hort.purdue.edu/newcrop/rubusicon.pdf

- Hummer,Kim. “Rubus Iconography: Antiquity to the Renaissance”. Purdue: Accessed September 25, 2013.http://www.hort.purdue.edu/newcrop/rubusicon.pdf

- Temkin, Owsei. “Byzantine Medicine: Tradition and Empiricism.” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 16 (January 1, 1962): 95–115. doi:10.2307/1291159.

- Sarah Brooks, Department of Medieval Art and The Cloisters. “Byzantium (ca. 330–1453)” Thematic Essay Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. The Metropolitan Museum of Art: Accessed September 9, 2013. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/byza/hd_byza.htm.

- “The Morgan Dioscorides (Circa 930 – 970) : From Cave Paintings to the Internet.” Accessed September 27, 2013. http://www.historyofinformation.com/expanded.php?id=2589.

- “Pedanius Dioscorides - Iris - The Morgan Library & Museum - Collections.” Accessed September 17, 2013. http://www.themorgan.org/collections/collections.asp?id=69.

- Jannick,Jules; Anna Whipkey; and John Stolarczyk. “Synteny of Images in Three Illustrated Dioscoridean Herbals: Julianna Anica Codex, Codex Neapolitanus, and Morgan 652”. Purdue. http://www.hort.purdue.edu/newcrop/pdfs/morgan.pdf%5B%5D

- Jannick,Jules; Anna Whipkey; and John Stolarczyk. “Synteny of Images in Three Illustrated Dioscoridean Herbals: Julianna Anica Codex, Codex Neapolitanus, and Morgan 652”. Purdue. http://www.hort.purdue.edu/newcrop/pdfs/morgan.pdf%5B%5D

- “The Morgan Dioscorides (Circa 930 – 970) : From Cave Paintings to the Internet.” Accessed September 27, 2013. http://www.historyofinformation.com/expanded.php?id=2589.

References

- Calkins, Robert G. Illuminated Books of the Middle Ages. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1983.

Further reading

- Evans, Helen C. & Wixom, William D., The glory of Byzantium: art and culture of the Middle Byzantine era, A.D. 843-1261, no. 161, 1997, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, ISBN 9780810965072; full text available online from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries

- Weitzmann, Kurt, ed., Age of spirituality: late antique and early Christian art, third to seventh century, no. 181, 1979, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, ISBN 9780870991790; full text available online from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries

External links

- Morgan Library's CORSAIR catalog entry, with link to 556 online images from the manuscript.