Moree Baths and Swimming Pool

Moree Baths and Swimming Pool is a heritage-listed swimming pool at Anne Street, Moree, New South Wales, Australia. It was the site of one of the successful protests by Aboriginal Australians for their rights during the Freedom Ride in February 1965. The site was added to the Australian National Heritage List on 6 September 2013.[1]

| Moree Baths and Swimming Pool | |

|---|---|

.jpg) Student Action for Aborigines protest outside Moree Artesian Baths, February 1965 | |

| Location | Anne Street, Moree, New South Wales, Australia |

| Coordinates | 29.4743°S 149.8466°E |

Australian National Heritage List | |

| Official name: Moree Baths and Swimming Pool | |

| Type | Listed place (Indigenous) |

| Designated | 6 September 2013 |

| Reference no. | 106098 |

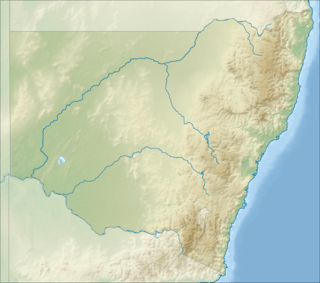

Location of Moree Baths and Swimming Pool in New South Wales | |

History

In early 1965 a group of students from the University of Sydney led by Aboriginal student activist Charles Perkins embarked upon a bus trip known as the Freedom Ride through outback NSW and Queensland to highlight racial inequalities in Australia at the time. The trip was based on the "Freedom Rides" that occurred as part of the civil rights movement in the United States in the early 1960s. The bus travelled to number of towns where racial discrimination had been identified with the aim of highlighting the inequalities and raising the profile of this issue amongst the broader Australian community. A number of towns were visited including Walgett and Kempsey but in Moree, where a ban on Aboriginal use of the local pool was in force, the trip gained a national profile in the media and raised the profile of Charles Perkins as an iconic figure for the Indigenous community.[1]

The events at the Moree Swimming Baths in February 1965 constitute a defining moment in the history of race relations in Australia. The activities of the Student Action for Aborigines group at Moree drew the attention of the public to the informal and institutional racial segregation practised at that time in outback towns in New South Wales. The events at Moree also highlighted the failures at both state and federal levels; while both spoke rhetoric of inclusion into the wider Australian society, Aboriginal people in country towns were still being excluded from sharing basic facilities. The publicity that the events at the Moree baths attracted contributed to shaping a climate of opinion resulting in a resounding Yes vote in the 1967 referendum, leading to a change in the Australian Constitution to allow the Australian Government to make laws specifically for Aboriginal people. The constitutional amendment provided the legal basis for subsequent Australian Government involvement in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander affairs, and also led to increased recognition of the importance of Indigenous rights in Australia.[1]

The Freedom Ride and the events at Moree have their origins in a heightened concern about racial discrimination in Australia after the Second World War. In 1945 the international community, in its attempts to provide peace and security in a world traumatised by the social and economic disruption of total war, agreed to recognise the political aspirations of, and to promote self-government in, colonised countries.[2] As a signatory to the United Nations Charter, and under pressure from independence movements in many of its colonies, Britain began to divest itself of its colonies immediately after the war: India gained independence in 1947, quickly followed by Ceylon and Burma in 1949 and Malaya, Sudan and Ghana in the 1950s. While these countries were proud of their independence from Britain, many of them elected to remain within the Commonwealth of Nations. The "Commonwealth club" provided a forum where the heads of government of the newly independent states met on equal terms with the heads of older self-governing Dominions like Australia, New Zealand, Canada and South Africa.[1]

In 1960 the British Prime Minister, Harold MacMillan responded to the Sharpeville massacre by delivering his "Winds of Change" speech to the South African Parliament. The speech recognised the inevitable growth of African national consciousness, which could no longer be ignored. MacMillan's speech was not welcomed in South Africa, with its apartheid laws that entrenched racial segregation, economic exploitation, and discrimination. In response, South Africa declared itself a republic in 1961, a move that threatened to divide the Commonwealth. The Australian Prime Minister, Robert Menzies, and Harold MacMillan tried to develop a form of words that would keep the Commonwealth intact. However, the final statement released at the end of the 1961 meeting of Commonwealth Prime Ministers expressed concern at the effect that South Africa's racial policies could have on relations between Commonwealth countries that were members of a multi-racial association of people.[3][1]

Menzies always championed the Commonwealth of Nations and it is not surprising that he worked with MacMillan to try to keep it intact. Privately, however, he questioned whether the newly independent nations could ever equal the old Commonwealth countries where British descendants and values prevailed.[4] He declined to become involved in overt criticism of apartheid, arguing that it was an internal matter for South Africa in which Australia should not interfere. Despite the government's silence, an anti-apartheid movement began to form which included the National Union of Australian University Students.[5][1]

South Africa was not the only country where there were laws institutionalising segregation and racial discrimination. In the early 1960s, protests by the civil rights movement against racial segregation laws in the United States of America led to brutal response by police in southern states. The police response and subsequent mass jailing received widespread coverage in Australia. In response to the mass protests and arrests in Birmingham, Alabama, the American President, John Kennedy, introduced a Civil Rights Bill to Congress in 1963. His successor, Lyndon Johnson, sought to push the bill through Congress in the early months of 1964. Sydney University students decided to protest outside the United States consulate on 6 May 1964 in support of the Bill, and against the senators from southern states who were attempting through filibuster to prevent its passage. When police began arresting protestors, fellow students tried to free them. The initial scuffle turned into what one newspaper described as "an all-in brawl", leading to extensive media publicity.[6][1]

International and some local reports of the demonstration included suggestions that demonstrators were hypocritical because they focused on fashionable American civil rights issues but did not consider the treatment of Australia's Indigenous minority, which was also racially discriminatory. In 1965, assimilation rather than segregation had been Australian Government policy for at least a decade, but the Australian Government powers were limited to persuasion since Aboriginal policy was firmly a matter for the state governments at this time. In his statement after the 1961 Native Welfare Conference, the Hon Paul Hasluck, the Australian Government Minister for Territories, described this policy as one that would enable Aboriginal people to:[1]

"... live as members of a single Australian community, enjoying the same responsibilities, observing the same customs and influenced by the same beliefs, hopes and loyalties as other Australians."[1]

Discriminatory legislation was removed by the Australian Government and state governments in the early 1960s. The last two states to grant Aboriginal people voting rights were Western Australia in 1962, and Queensland in 1962 (for Australian elections) and 1965 (for state elections). In New South Wales, Aboriginal policy was managed by the Aborigines Welfare Board (AWB), which sought either to keep people on its managed stations or to exert control over the rest through a network of district welfare officers.[7] Typically, Aboriginal people lived on the fringes of towns, either in unhealthy shanty settlements or in highly regulated stations. They continued to suffer the effects of racial discrimination at a local level, socially, economically, and culturally.[1]

There was, however, a growing movement for Aboriginal rights in the late 1950s and early 1960s, represented most clearly by the organisations brought together by the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines (in 1964 Torres Strait Islanders were added so that the acronym became FCAATSI). Students had not been a significant part of this movement, but after the criticisms of their actions outside the US Embassy in May 1964, and influenced by the arrival the year before of Charles Perkins and Gary Williams as the first two Aboriginal students at the University of Sydney, they began to organise a very successful student-organised demonstration and concert. This took place on National Aborigines Day in Hyde Park in Sydney and was followed by the formation in July 1964 of a more permanent organisation, Student Action for Aborigines (SAFA). This organisation drew people from many of the political, religious and recreational clubs in the University and it had an Aboriginal student, Charles Perkins, as Chairman.[8][1]

The proposed Freedom Ride with its focus on racial discrimination and segregation resonated with Charles Perkins' life. He was born at The Bungalow in Alice Springs. His Eastern Arrernte mother, recognising there were limited educational opportunities in Alice Springs, took up an offer for him to go to St Francis House, an Anglican home for boys of mixed Aboriginal and other descent in Semaphore South, Adelaide.[9] He had encountered discrimination against Aboriginal people in Alice Springs and this continued when he moved to Adelaide. A story from his late teens demonstrates the callous treatment meted out to Aboriginals. He went to a dance at the Port Adelaide Town Hall where he summoned up the courage to walk across the room and individually asked each girl for a dance only to be told, 'We don't dance with blacks'. The experience, he said, scarred his mind and undermined his confidence and self respect.[10][1]

In the early 1950s Charles began playing soccer at St Francis House. His outstanding skills as a soccer player led him to England in 1957 where he trialled for Everton. Although he was offered a position he rejected this due to his treatment at the club and ended up playing as an amateur for the Bishop Auckland club. In 1958, he returned to Australia to marry Eileen Munchenburg and take up matriculation studies.[11] He continued to play soccer, taking on the position of captain coach for Adelaide Croatia before moving to Sydney where he also accepted the role of captain coach of the Sydney Pan Hellenic team, using it to help finance his way through University. In 1963, he entered the University of Sydney where he became increasingly involved in campaigns against racial discrimination and segregation against Aborigines, "recognising too their rights as a people".[1]

One of the suggested activities for the SAFA group, which was inspired by the Freedom Rides in America, was a bus tour of Aboriginal settlements. Unlike the American Freedom Rides, which aimed to challenge segregation on interstate buses and at interstate bus terminals in the south, SAFA planned their bus tour to highlight the plight of Aborigines in rural Australia on a range of issues. Their aim was to undertake a social survey into the extent of racial discrimination in country towns, and then to draw discrimination to the attention of the wider Australian public through the press, radio and television. They wanted to point out the discriminatory barriers and inadequacies in health and housing as well as supporting Aboriginal people in challenging the status quo. The group decided to adopt Martin Luther King's approach of non-violent resistance when dealing with opponents.[1]

Preparations for the trip included a number of fundraisers including folk concerts, dances and sales of Christmas cards. SAFA also received donations from the Student Union, and each student participant contributed ten pounds. They heard talks and produced a reading list about the barriers facing Aboriginal people in outback New South Wales to help them prepare themselves for the trip.[12] The group also had several people as sources of information on discrimination and segregation in the towns in northern New South Wales. One was Jack Horner of the Aboriginal Australian Fellowship. He provided information on issues in a number of towns in outback New South Wales including Walgett, Moree and Kempsey. He also advised the SAFA about recent reports and conferences dealing with Aboriginal health and education.[13] Charles Perkins, the President of the group was another source of information for the bus trip. During the summer, he worked for the Foundation for Aboriginal Affairs where his interaction with job seekers, evicted families and those requiring access to social services enabled him to gain an understanding of the issues faced by Aboriginal people in New South Wales. He gained further insight into racial prejudice and segregation in some of the towns when he was invited to join a light plane tour through New South Wales with a journalist, Craig Williams, and the Reverend Ted Noffs, who had agreed to help the students design their survey.[14][1]

.jpg)

With all the preparations completed, the Freedom Ride bus left Sydney on 13 February 1965. Its first stop was Wellington where the students conducted surveys and investigations, highlighting social injustices and uncovering evidence of racial discrimination. However, without local Aboriginal contacts and with insufficient firm information to justify a demonstration they moved onto to the next town, Gulargambone. While the conditions under which Aboriginal people lived there were quite shocking, there was not a clear case of racial discrimination on which to demonstrate. The next stop was Walgett, and here the Freedom-riders took action. Walgett had both an existing group of Aboriginal activists and some clear cases of racial discrimination. It proved to be the first real showdown for the Freedom Riders. They spent their first day conducting interviews to obtain information about segregation and racial discrimination and found that the cinema, the Returned Servicemen's League (RSL) club, the town's two hotels and a frock shop were all segregated.[15] The manager of the Oasis Hotel stated that he did not allow Aboriginal people into the public bar because his white patrons did not want them admitted. He said he would lose his white customers and business if he allowed Aboriginals to drink there. Of more concern was the fact that Aboriginal people, including Aboriginal ex-service men, who applied to join the Walgett RSL Club, were denied membership.[1]

The Freedom Riders picketed the Walgett RSL club from noon until sunset holding placards stating "Walgett: Australian's disgrace", "Bar the Colour Bar", "Good enough for Tobruk - why not Walgett RSL?".[16] The picket provoked much heated discussion and the white community in Walgett expressed its anger towards the Freedom Riders. The minister of Anglican Church Hall in Walgett, where the students were staying, had warned them that morning that they would not be allowed to stay if they demonstrated against the RSL. After the demonstration, the minister and three churchwardens gave the students two hours to vacate the hall.[17][1]

A line of cars and a truck followed the bus when it left Walgett. It was night time and the students could not see their followers. The truck attempted to run the bus off the road twice; on the third attempt, it clipped the bus forcing it off the road and over an embankment. While nobody was injured during this incident, the students were further alarmed when the convoy of cars stopped, but were relieved to find that the cars belonged to members of the Aboriginal community who had tried to provide an escort to protect the bus from hostile white residents. The bus returned to Walgett where the driver reported the incident to the police. When the police had finished taking all the statements, the Freedom Riders left Walgett, which remained a bitterly divided town.[18][1]

Walgett was the first big test for the students. While their protest did little to change the attitudes of the townsfolk, they encouraged the Aboriginal community to push for change. Aboriginal people who participated in pickets were bitter at the ongoing discrimination they experienced in their town and they continued to protest and agitate for desegregation in the establishments that still upheld a colour ban after the protestors left.[19] Seven months after the visit of the Freedom Ride, some students returned to Walgett to assist in an Aboriginal demonstration to desegregate the local cinema.[1]

Initially, there was little media interest in the events in Walgett.[19] However, a report by Bruce Maxwell, a cadet reporter for the Herald, brought the SAFA Freedom Ride into the national spotlight. The Sydney Morning Herald and The Daily Mirror newspapers as well as TV and radio now began to report on the next stage of the Freedom Ride in Moree.[20][1]

The pattern of racial discrimination and segregation in Moree was similar to that found in Walgett with some firms refusing to employ Aboriginals, and most hotels refusing to serve them. The students' attention, however, focused on the swimming pool where a council by-law prevented Aboriginal people's entry. This was an example of discrimination enforceable under local ordinance so it was seen to be similar to officially sanctioned apartheid in South Africa and segregation in the United States. In addition, a local councillor, alderman Bob Brown, had repeatedly tried to get the council to allow Aborigines to use the baths, but to no avail - he could not even get a seconder for his motion.[21][1]

.jpg)

Initially, the Freedom Riders held a picket at the Moree council chambers to protest against the exclusion of Aboriginal people (except for school children during school hours) from the Moree baths. The next day Bob Brown and the Freedom Riders tried to take Aboriginal children into the pool. The pool manager argued heatedly with the student leaders. The impasse ended when the mayor agreed to allow the children in. That evening, the students held a public meeting to explain why they were in Moree and to present their survey results. Initially the largely white audience reacted angrily and some left, but after discussion the atmosphere changed. The meeting concluded by passing a motion that the by-law segregating the pool should be removed, which the mayor said he would take to the council.[22][1]

.jpg)

The Freedom Riders left Moree the next day, jubilant that the colour ban had been lifted.[23] While the students travelled to Boggabilla and then to Warwick in southern Queensland, Bob Brown tried to take another group of Aboriginal children to the pool but the pool manager refused them entry and decided to close the pool. Following an emergency council meeting, the mayor arrived and ordered the manager to re-open the pool and enforce the by-law providing for segregation of the baths. The following day Bob Brown called the Freedom Riders to let them know what had happened. Charles Perkins had flown to Sydney to be interviewed for a television programme. The students phoned the Methodist Minister in Moree who confirmed Bob Brown's story and told them that they would not be welcome in Moree. The students decided to turn the bus around and return to Moree.[24][1]

.jpg)

The Freedom Riders stopped at Inverell that night and picked up Charles Perkins in the morning. Charles felt that the opportunity to achieve a "break through" was at stake and saw Moree as the place to do this.[25] On returning to Moree, the Freedom Riders again collected a number of Aboriginal children from the mission to gain admittance into the swimming pool. They attempted to enter the pool with the children for three hours. By this time, a large crowd of locals had gathered outside the pool. It was hostile and tempers were inflamed. Some locals threw eggs and tomatoes. They knocked some students down and at least one was punched. Fights broke out and police arrested several crowd members.[26] The media reported the attacks on the students as "little different from the American South".[27][1]

.jpg)

A breakthrough came when the mayor of Moree, Bill Lloyd, came down to the baths and informed the students and the crowd that he was prepared to sign a motion to rescind the 1955 by-law. After some negotiation, the Freedom Riders accepted these assurances and agreed to leave. They boarded the bus under a hail of eggs and tomatoes and the police provided a protective escort as the bus left town.[28][1]

.jpg)

The Freedom Riders continued their journey, visiting the coastal towns in northern New South Wales to undertake their surveys and highlight instances of racial discrimination. While the students demonstrated against particular instances of discrimination and segregation in towns like Kempsey and Bowraville, the local reactions were more muted than those in Moree.[29][1]

The reports and photos in the major newspapers of the events at Moree shocked many white Australians, making them aware of the plight of Aboriginal people.[30] By drawing attention to both informal and officially sanctioned segregation and racial discrimination, the Freedom Ride helped to show that governmental rhetoric, that Aboriginal people should share in the benefits and opportunities of Australians generally, was not being applied in practice.[1]

The Freedom Riders highlighted the fact that, contrary to government policy, segregation and discrimination were endemic in many of the rural towns of New South Wales. The council ordinance prohibiting Aboriginal people from using the Moree baths demonstrated that discrimination was officially sanctioned in some cases. Whether the Australian Government was unable or unwilling to tackle such contradictory policies is unclear. Section 51 of the constitution, prohibited the Government from passing laws specifically for Aboriginal Australians. There was also a lack of will to use the external affairs powers to address racial discrimination.[1]

By highlighting endemic racism in Australia, the Freedom Ride contributed to the passage of the 1967 referendum, which altered the constitution to allow the Commonwealth to make laws for Aboriginal people. It also contributed to the passage in 1975 of legislation prohibiting racial discrimination and encouraged some Aboriginal people to become active in challenging the status quo of segregation and discrimination. The Freedom Ride has been described as one of those transitional moments in Australian history when one era fades and another takes its place.[31][1]

Description

Moree Baths and Swimming Pool is at about 0.5ha, Lot 20 bounded by Anne Street, Gosport Street and Warialda Street in Moree.[1]

The Moree Hot Artesian Pool Complex (Moree baths) is owned and managed by the Moree Plains Shire Council. The original hot pool opened in 1895 when the first bore that tapped into the Great Artesian Basin was completed. The bore delivered mineral waters, heated naturally to about 41 degrees Celsius. A small basin was originally excavated and gravelled. This was later upgraded with a small wooden lined basin for bathing. The original bore ceased to flow in 1957, and the hot mineral waters are now pumped to the baths. Currently the large municipal complex comprises three tiled pools.[1]

Condition

The building is still in use and is in good condition. Since 1965 the exterior has been modified and there have been minor refurbishments to the interior of the baths and swimming pool. These modifications have not affected its heritage value relating to the 1965 Freedom Ride.[1]

Heritage listing

In 1965 student protest actions at the Moree baths highlighted the racial discrimination and segregation experienced by Aboriginal people in Australian rural towns and the outback and forced the broader Australia community to look at the way it treated its Indigenous population. The protest was an important contributor to the climate of opinion which resulted in a yes vote in the 1967 referendum to change the Australian Constitution regarding the status of Aboriginal Australians. That change provided a legal basis for subsequent Australian Government involvement in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander affairs and an increased recognition at local, state, and national levels of the importance of Indigenous rights in Australia.[1]

The events that occurred at the Moree baths in 1965 also have a special association with the life and works of the Aboriginal activist Dr Charles Nelson Perrurle Perkins AO. Moree was the place where the public first saw him confront people with awkward truths about the treatment of Aborigines. This combined with other events that occurred in the wider Freedom ride, brought Charles Perkins to public prominence as a leading Aboriginal activist and established him as an iconic figure for both young and older Aborigines alike. In addition it clearly demonstrated his commitment to achieving equity for Aboriginal people in Australia, which became a lifelong cause.[1]

Moree Baths and Swimming Pool was listed on the Australian National Heritage List on 6 September 2013 having satisfied the following criteria.[1]

Criterion A: Events, Processes

The Moree baths has outstanding national heritage value under criterion (a) as the place where student protests in 1965 highlighted the legalised segregation and racism experienced by Aboriginal people in outback Australia. It brought the racial discrimination and segregation experienced by the Aboriginal population in Australian country and rural towns to the attention and consciousness of the white Australian population. It forced Australia to look at the way it treated its Indigenous population and showed that racial segregation continued in many towns. The protest was an important contributor to the climate of opinion which produced a yes vote in the 1967 referendum to change the Australian Constitution. From that change came a legal basis for subsequent Commonwealth involvement in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander affairs and an increased recognition at local, state, and national levels of the importance of Indigenous rights in Australia.[1]

Criterion H: Significant people

The Moree baths has outstanding heritage value to the nation under criterion (h) as the place that has a special association with the life and works of the Aboriginal activist Dr Charles Nelson Perrurle Perkins AO. The events at the Moree baths in 1965 brought him into public prominence as a leading Aboriginal activist and it was here that his tactic of confronting people with awkward truths about their treatment of Aborigines first emerged in a public context. This pattern was repeated throughout his life even when it resulted in costs to him personally. The events that occurred in Moree, and the wider Freedom ride, established Charles Perkins as an iconic figure for both young and older Aborigines alike. In addition it clearly demonstrated his commitment to achieving equity for Aboriginal people in Australia, something that became a lifelong cause.[1]

References

- "Moree Baths and Swimming Pool (Place ID 106098)". Australian Heritage Database. Department of the Environment. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- United Nations 1945: Article 73

- Martin 2000: 201

- National Archives of Australia

- Curthoys 2002: 2; Clark 2008: 5

- Curthoys 2002: 6-7

- Goodall 1996: 265

- Ford 1965: 4; Spigelman 1965: 116-117; Curthoys 2002: 8-10

- Briscoe 2000: 253

- The Times 19 October 2000

- Briscoe 2000:254

- Talkabout 1964 No.1 and No.2

- Letter from J. Horner to J. Spigelman 19 January 1965

- Curthoys 2002: 50

- Read 1988:47

- Read1988: 48; Curthoys 2002: 98

- Read 1988: 48

- Read 1988:49

- Clark 2008:171

- Curthoys 2002:7

- Clark 2008:172

- Curthoys 2002: 136-142

- Messenger 2002: 2

- Clark 2008:173

- Read 1988: 51

- Curthoys 2002: 155-158

- Messenger, 2002:3

- Curthoys 2002

- Spigelman 1965: 49; Curthoys 2002; Ch. 7

- Cameron 2000: 12; Clark 2008: 178

- Clark 2008: 11

Bibliography

- Clark, J. 2008, Aborigines and Activism - Race, Aborigines and the Coming of the Sixties to Australia, University of Western Australia Press: Crawley, WA.

- Behrendt L. 2007. On Leadership - Inspiration from the life and Legacy of Dr Charles Perkins. The Journal of Indigenous Policy, Issue 7, August 2007.

- Briscoe G. 2000. Kwementyaye Perrurle Perkins: a personal memoir. Aboriginal History 24: 251- 255.

- Cameron K. 2000. Discovering democracy: Aboriginal people struggle for citizenship Rights. Discussion Paper 6, New South Wales discovering democracy professional development committee.

- Curthoys A. 2000. Charles Perkins: no longer around to provoke, irritate, and inspire us all. Aboriginal History 24: 256- 258.

- Curthoys A. 2002, Freedom ride: a freedom rider remembers, Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, NSW.

- Curthoys, Ann. 2004, The Freedom Ride - Its Significance Today, Public lecture National Museum of Australia. Public Lecture 4 September 2004.

- Ford G.W. 1965. The Student Bus: SAFA interviewed. Outlook 2: 4-10.

- Goodall, Heather. 1996. Invasion to Embassy: Land in Aboriginal Politics in New South Wales, 1770-1972, Allen and Unwin, Crows Nest, NSW.

- Gunson N. 2000. The imprimatur of Charles Perkin on Aboriginal History. Aboriginal History 24: 258-259.

- Hasluck P. 1961. Native Welfare Conference. Statement by leave by Minister for Territories (the Hon. Paul Hasluck M.P.) in the House of Representatives on Thursday 20 April 1961.

- Henty-Roberts C. 2000. Kwementyaye Perkins (Dr Charles Nelson Perrule Perkins, AO) 1936 - 2000. Indigenous Law Bulletin, October 2000, Volume 5, Issue 3.

- Hughes R. 1998. Interview with Charles Perkins for Australian Biography project. Screen Australia. Downloaded on 25 May 2012 from http://www.australianbiography.gov.au/subjects/perkins/interview1.html

- Parliament of NSW Government: 2000. Hansard, Legislative Assembly, Death of Charles Nelson Perkins, 1 November 2000 p 9494

- Perkins C. 1975. A Bastard Like Me. Sydney: Ure Smith.

- Spalding. I. 1965. No Genteel Silence. Crux: The Journal of the Australian Student Christian Movement 68: 2-3.

- Marks K. 2000. Obituary Dr Charles Nelson Perrurle Perkins, AO. The Independent, Friday Review 20 October.

- Martin A. 2000. Sir Robert Gordon Menzies. In M. Grattan (ed.) Australian Prime Ministers. Sydney: New Holland Publishers. pp. 174-205

- Maynard, John. 2011.The Aboriginal Soccer Tribe: A History of Aboriginal Involvement with the World Game (Broome: Magabala Books).

- Messenger R. 2002. A ride that began to close Australia's Black and White divide. Canberra Times, September 7.

- National Archives of Australia nd. Robert Menzies in office. Downloaded on 25 May 2012 from https://web.archive.org/web/20131113103332/http://primeministers.naa.gov.au/primeministers/menzies/in-office.aspx.

- Read P. 1988. 'Darce Cassidy's Freedom Ride. -University of Sydney. Student Action for Aborigines tour of NSW country towns in February 1965 and ABC reporter Darce Cassidy's tapes-' Australian Aboriginal Studies (Canberra), no. 1, pp. 45-53.

- Spigelman J. 1965a. Student Action for Aborigines. Vestes 8: 116-118.

- Spigelman J. 1965b. Reactions to the SAFA Tour. Dissent 14: 44-48.

- Spigelman J. 2001. A moral force for all Australians Walking Together, Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation 30: 12.

- Spigelman, J. 2005. 'Charles Perkins Memorial Oration 2005 by Chief Justice of New South Wales at the University of Sydney.

- United Nations 1945. Charter of the United Nations and Statute of the International Court of Justice. Downloaded on 25 May 2012 from http://www.un.org/en/documents/charter/index.shtml

Attribution

![]()

External links

![]()