Montdory

Montdory, pseudonym of Guillaume des Gilberts (baptized 13 March 1594; died between 17 November 1653 and 14 November 1654), was a French actor manager, recognized as "the most powerful tragedian of his day."[2]

Birth, family, and name

Montdory was born in Thiers and baptized there in the parish of Saint-Genès on 13 March 1594. He was named after his father, Guilhaume Dosgilberts,[3] who was a coutelier (cutlery maker).[4] The spelling of Guilhaume was often standardized to Guillaume, even during his lifetime. The Thiernaise patois article dos is translated into French as des, and the surname appears in various documents with 'z' instead of 's' and as one word or two (e.g., 'Dosgilbertz' or 'Desgilberts' or 'des Gilberts'). The family owned property in nearby Escoutoux, in the village of Les Giliberts (today Les Gilberts).[5] His mother was Catherine Sandry, sister of Guilhaume Sandry, a merchant, who served as his godfather.[6]

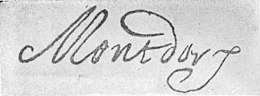

He adopted the pseudonym Montdory early in his career, and as an actor most of his contemporaries appear to have been unaware of his true surname and origin.[7] Didot's Dictionnaire générale of 1861 stated he was born in Orléans and his family name was unknown.[8] However, in 1867, Auguste Jal, in his Dictionnaire critique, reported the existence of a baptismal record of 9 October 1633 in the parish of Saint-Nicolas-des-Champs, Paris, in which Montdory's wife, Marie Berthelin, served as godmother and her husband's name is given as Guillaume Gilbert, Sr de Mondory.[9] Authors consistently wrote his pseudonym as Mondory or Mondori until 1925, when J. Fransen discovered that he himself signed it Montdory.[7]

Early career

He is first recorded as an actor on 31 March 1612 under the name Gilleberts "called Mondaury" in an act of association of a troupe organized by Valleran le Conte. Montdory was only eighteen and not yet a fully formed actor, since he only received half a share of the profits.[10] The company performed at the Hôtel de Bourgogne in Paris, and renewed their lease there in May 1612 in a contract with the Confrérie de la Passion signed by Valleran le Conte, in which Montdory is listed under the name Gillebertz.[11] Their success at the Bourgogne, where the rents were high, declined, and the company departed on a tour of the provinces and were in Holland in 1613, where they performed for the Prince of Orange. It is likely that Montdory, as well as the actor Bellerose, were members of the troupe at this time.[12] Valleran le Conte died not long after. [13]

In 1622 Montdory was with Charles Lenoir in a company supported by the Prince of Orange, which performed briefly in the Bourgogne. Montdory also performed at the Bourgogne in January 1624.[14] Montdory left the company of the Prince of Orange, when on 14 April 1624, he and the actors, Claude Husson and Claude Deschamps, among others, signed a contract for two years.[15] Later that year they were touring the northern part of France and Holland with their own company and performing in plays by Alexandre Hardy.[16] Montdory's career from 1627 to 1630 remains a mystery.[17]

Théâtre du Marais

In December 1629 the Royal Council granted the Troupe Royale an exclusive lease to the Bourgogne for three years.[18] In January or February 1630, Montdory, who was now in Paris, joined Lenoir and his troupe to perform Pierre Corneille's first play, Mélite, at the Berthault Tennis Court.[19] The production was so successful, the company was able, with the support of Cardinal Richelieu, to settle in their own theatre, later known as the Théâtre du Marais.[13] Just before moving into their new home, King Louis XIII ordered Lenoir and his wife, a fine actress who had appeared in the plays of Jean Mairet, to join the King's Players under Bellerose at the Hôtel de Bourgogne. This was probably intended by the king as a rebuke to Richelieu, who had openly expressed his preference for Montdory's players over those of the king.[13][20]

Montdory's troupe moved into their new theatre in 1634. Toward the end of that year Montdory presented Jean Mairet's masterpiece Sophonisbe. He performed Herod in Tristan l'Hermite's La Mariane with great success in 1636.[21] Probably his most famous role at the Marais was Don Rodrigue in Corneille's Le Cid in 1637.[2][13] In August of that year, while performing as Herod in a revival of La Mariane, with Richelieu in the audience, Montdory suffered what has variously been described as paralysis of the tongue,[13] a burst blood vessel,[22] or an apoplectic fit.[23] Whatever its cause, his persistent paralysis forced his retirement from the stage,[13] whereupon Richelieu awarded him with a generous pension.[2]

Montdory was "an excellent businessman as well as a fine actor in the old declamatory style".[13]

Retirement and death

Montdory was again in Paris in 1643, but then returned to Thiers, where he lived in obscurity.[24] The last known document signed by him (in the presence of a notary in Montdory's home in Thiers) is dated 17 November 1653 and records a gift of 6,000 livres to his son-in-law Jean de Fédict.[25] Another Thiers document of 14 November 1654 records a gift made by Montdory's widow, Marie Bertelin,[26] to their daughter, Catherine. Scholars have therefore concluded Montdory must have died between those dates in Thiers.[27]

Notes

- Cottier 1937, after p. 222.

- Roy 1995.

- Cottier 1937, p. 13 (copy of the baptismal record).

- Mongredien 1972, p. 131.

- Cottier 1937, pp. 13–15.

- Cottier 1937, p. 20,

- Cottier 1937, pp. 13–14.

- J., 1861.

- Jal 1867, p. 878; cited by Cottier 1937, p. 14.

- Wiley 1960, p. 100.

- Wiley 1973, p. 9.

- Wiley 1960, p. 101; Wiley 1973, p. 9.

- Hartnoll 1983, p. 558.

- Wiley 1973, p. 10.

- Wiley 1960, pp. 101–102; Cottier 1937, after p. 62.

- Wiley 1960, p. 102; Hartnoll 1983, p. 558.

- Howe 2006, p. 523.

- Powell 2000, p. 15.

- Hartnoll 1983, p. 558 (omits theatre name); Powell 2000, p. 15; Garreau, "Corneille, Pierre", p. 554, in Hochmann 1984 (date given as "early 1630"); Howe 2006, pp. 522–523, 541. Howe says the performances were in January or February and suggests the possibility that Mélite had been given earlier, in October or November 1629, at the Bourgogne by Le Noir and his troupe without Montdory.

- Howarth 1997, pp. 103–104.

- Wiley 1960, pp. 102–103.

- Howarth 1997, p. 6.

- Howarth 1997, p. 168.

- Mongrédien 1972, p. 132.

- Cottier 1937, p. 256; Deierkauf-Holsboer 1958, p. 10. The death date 10 November 1653 given in the anonymously authored article in The Encyclopædia Britannica (Anonymous 1991), is inconsistent with this document.

- Her surname has been variously spelled Bertelin (Jal 1867, p. 878; Mongredien 1972, p. 132), Bertellin (Cottier 1937, p. 257), or Berthelin (Deierkauf-Holsboer 1958, p. 10).

- Cottier 1937, pp. 256–257; Deierkauf-Holsboer 1958, p. 10.

Bibliography

- Anonymous (1991). "Montdory", vol. 8, p. 279, in The New Encyclopædia Britannica, 15th edition. Chicago. Also at "Montdory", Encyclopaedia Britannica online.

- Cottier, Elie (1937). Le comédien auvergnat Montdory: Introducteur et interprète de Corneille. Clermont-Ferrand. OCLC 25476165.

- Deierkauf-Holsboer, S. Wilma (1958). Le Théâtre du Marais: II. Le berceau de l'Opéra et de la Comédie-Française, 1648–1673. Paris: Librairie Nizet. OCLC 889201044.

- Hartnoll, Phyllis, editor (1983). The Oxford Companion to the Theatre, fourth edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780192115461.

- Hochman, Stanley, editor (1984). McGraw-Hill Encyclopedia of World Drama (second edition, 5 volumes). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 9780070791695.

- Howarth, William H., editor (1997). French Theatre in the Neo-Classical Era 1550–1789. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (2008 digital reprint: ISBN 9780521100878.)

- Howe, Alan (2006). "Corneille et ses premiers comédiens", Revue d'Histoire littéraire de la France, vol. 106, no. 3 (July–September, 2006), pp. 519–542. JSTOR 23013593.

- J., A. (1861). "Mondory ou Mondori", vol. 35, p. 963, in Nouvelle biographie générale depuis les temps les plus reculés jusqu'à nos jours. Paris: Firmin Didot frères. Copy at Google Books.

- Jal, Auguste (1867). "MONDORY (Guillaume-Gilbert, Sr de)", p. 878 in Dictionnaire critique de biographie et d'histoire : errata et supplément pour tous les dictionnaires historiques d'après des documents authentiques inédits. Paris: Henri Plon. Copy at Gallica.

- Mongrédien, Georges (1972). Dictionnaire biographique des comédiens français du XVIIe siècle, second edition. Paris: Centre national de la recherche scientifique. ISBN 9780785948421.

- Powell, John S. (2000). Music and theatre in France, 1600-1680. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198165996.

- Roy, Donald (1995). "Montdory", pp. 758–759, in The Cambridge Guide to the Theatre, second edition, edited by Martin Banham. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521434379.

- Wiley, W. L. (1960). The Early Public Theatre in France. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. OCLC 331219. Greenwood Press reprint (1973): ISBN 9780837164496.

- Wiley, W. L. (1973). "The Hotel de Bourgogne: Another Look at France's First Public Theatre", Studies in Philology, vol. 70, no. 5, pp. 1–114. JSTOR 4173826.