Monrobot XI

The Monroe Calculating Machine Mark XI (or "Monrobot XI") was a (general-purpose) stored-program electronic digital computer introduced in 1960 by the Monroe Calculating Machine Division of Litton Industries.

Economics and deployments

Upon introduction in May 1960,[1] the Monrobot XI sold for US$24,500. In March 1961, the US Army reported[2] that seven units had been made. In November 1961, the price remained unchanged and leasing ran US$700 monthly.[3] By 1966, there were about 350 machines in the field, but by 2013 no machines were known to remain in existence.[4]

Appearance and operating environment

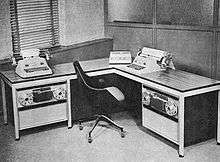

The bare-bones Monrobot XI resembled an ordinary steel desk in length, breadth, and height, surmounted by an ordinary typewriter and a breadbox-like-volume control panel. At a weight of 375 pounds (170 kg),[2][5] its purveyors pronounced it portable.[6] It could operate outside of an air-conditioned room (tolerating +-25% voltage margins at 110 °F (43 °C) ambient temperature), using a conventional mains power line (15 A, 110 V, 60 c.p.s. service) and about half as much electrical power (850 W) as a toaster.

Architectural philosophy

Unlike virtually all electronic digital computers ever built, as an early[1] machine, the Monrobot XI was one of the small family of computers which totally lacked random-access memory (RAM), which alternative would have allowed it to access all memory words equally fast. Even by the time it was introduced, it was not uncommon for electronic digital computers to use magnetic-core memory for RAM, the price (per bit) of which would fall[7] from over US$1 in the early 1950s to about US$0.20 by the mid-1960s. But to keep the cost of the machine very low, instead the Monorobot XI used a form of memory in which words were cyclically accessible in sequential order, using an electromechanical moving part called magnetic drum memory. Thus, physically, it bore some resemblance to the hypothetical Turing machine of computer science, albeit with the latter's tape being of finite length and joined end-to-end, and then finally replicated many times collaterally. The long latency of memory access, which followed from intensive use of such a macroscopic moving part, made the Monrobot XI operate very slowly, despite the exploitation of non-mechanical electronics for logical functions.

The Monorobot XI might best be thought of as a modernized (solid-state), low cost version of the IBM 650, the world's first mass-produced computer, leased at US$3,250 per month[8], almost 2,000 of which were made between 1954 and 1962, 800 by 1958. Both the IBM 650 and Monrobot XI used a magnetic drum for primary memory, but the former used vacuum tubes and bi-quinary coding, rather than transistors and binary coding, for its electronics.

Persistent electro-mechanical memory

The Monrobot XI's rewritable, persistent memory consisted of a rotating magnetic drum storing 1,024 words of 32-bits, which could record either a single integer or a pair of zero/single-address instructions. The average access time of 6,000 microseconds implies the drum made a rotation every 12 milliseconds, i.e. rotated at 5,000 RPM. Even the high-speed registers of the central processing unit (CPU) physically resided on the drum, being replicated 16 times (with 16 times as many re-write heads distributed around the drum periphery), so that they might be read or written 16 times as fast as the bulk of persistent memory.

Electronics

Save for the neon lamps in the control panel and 10-30 vacuum tubes employed for output devices, the electronics used only discrete solid-state components, including 383 transistors and 2,300 diodes. (The arithmetic unit alone used 190 transistors and 1,675 diodes.) This astoundingly small (383) active component count - little more than in the Manchester Baby (250), the world's first (1948) stored-program Turing-complete computer, is in stark contrast to the many millions of transistors present in modern microprocessors; this was a key advantage of using its slow, now-primitive, electromechanical memory, which exploited measuring a drum's rotational angle, not adding switches, to multiplex bits. Even Intel's first (1971) microprocessor, the four-bit Intel 4004, required about 2,300 transistors in its monolithic design.

Construction was via pluggable printed-circuit boards, allowing economical partial replacement of a broken system as the principal means of repair. This continued an electronics tradition pioneered when relatively unreliable short-lived vacuum tubes had been used as active components, prior to the advance to more modern, highly reliable solid-state transistors which the Monorobot XI exploited. (Unlike vacuum tubes, which were always plugged into sockets, discrete transistors were almost always permanently soldered into place.)

Programming and operating speed

The arithmetic unit performed computations using the binary number system, with machine-language programming using hexadecimal digits, employing the unusual digit nomenclature set of {0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,S,T,U,V,W,X}. Statistically, addition of 32-bit integers required 3ms to 9ms, multiplication 28ms to 34ms, and division 500ms. The longer durations reflect the mean latency (6ms) of accessing a persistent memory location, rather than a register, for the second of the two operands.

The computer could be programmed using an assembly language system called QUIKOMP(TM), but its simple machine language instruction set and slow operation speed encouraged many programmers to code directly in machine language.

The Monrobot computer series in popular culture

An episode of the animated television series Futurama, originally airing in 2001, features a humanoid robot resembling mid-20th century sex symbol Marilyn Monroe, named Marilyn Monrobot, as a character within a film viewed by the episode cast.

References

- Recollections of the Monrobot by Norma Edwins, The Bulletin of the Computer Conservation Society (ISSN 0958-7403) #31, Autumn 2003

- A Third Survey of Domestic Electronic Digital Computing Systems pg 0672ff. Report No. 1115, March 1961 by Martin H. Weik, Ballistic Research Laboratories, Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland (US Army)

- (November 1961 magazine ad)

- Monrobot - one of many "lost" in history by Donald Caselli

- . 196004.pdf. "News of Computers and Data Processors: ACROSS THE EDITOR'S DESK: THE MONROBOT MARK XI COMPUTER". Computers and Automation. 9 (4B (4)): 6B (24). Apr 1960. Archived from the original on 2018-08-01. Retrieved 2018-06-29.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Portable Robot The New Yorker (March 19, 1960)

- Encyclopædia Britannica, 14th revised edition (1966), Vol. 6, pg. 247

- Campbell-Kelly, Martin (2013). Computer: A History of the Information Machine. Westview. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-429-97500-4.

External links

- detailed technical specifications of the Monorobot XI

- pg 75 (on the Monrobot XI) in Digitale Kleinrechner by Günter Schubert (Springer-Verlag, Mar 13, 2013)

- cover page of A Brief History of the Monrobot XI Computer by Donald O. Caselli, May 15, 2011

- illustrated memoir (March 15, 2007) by John Mann, about use of the Monorobot XI at Scotch College in Melbourne, Australia during the 1970's

- photograph of Monrobot XI control panel

- photograph of Monrobot XI QUIKOMP(TM) reference card

- "Monrobot XI" (pdf). AUERBACH Standard EDP Reports. 6: 715–804.

- Monrobot XI Program Manual. 1964.

- "Monrobot XI Computer". www.dopecc.net.