Moltke's Palace

Moltke's Palace or Christian VII's Palace is one of the four palaces of Amalienborg in Copenhagen that was originally built for Lord High Steward Adam Gottlob Moltke. It is the southwestern palace, and since 1885, has been used to accommodate and entertain prominent guests, for receptions, and for ceremonial purposes.[1]

History

Moltke's Palace, currently known as Christian VII's Palace, was originally built for Lord High Steward Adam Gottlob Moltke. Between his two wives, Moltke was said to have had 22 sons, five of whom became cabinet ministers, four who became ambassadors, two who became generals, and all of whom went into public service.[2] According to Eigtved’s master plans for Frederikstad and the Amalienborg Palaces, the four palaces surrounding the plaza were conceived of as town mansions for the families of chosen nobility. Their exteriors were identical, but interiors differed. The site on which the aristocrats could build was given to them free of charge, and they were further exempted from taxes and duties. The only conditions were that the palaces should comply exactly to the Frederikstad architectural specifications, and that they should be built within a specified time framework.

Motke's Palace was erected in 1750–54 by the best craftsmen and artists of their day under the supervision of Eigtved. It was the most expensive of the four palaces at the time it was built, and had the most extravagant interiors. Its Great Hall (Riddersalen) featured woodcarvings (boiserie) by Louis August le Clerc, paintings by François Boucher and stucco by Giovanni Battista Fossati, and is acknowledged widely as perhaps the finest Danish Rococo interior.[1]

On 30 March 1754, the mansion formally opened coinciding with the King’s thirtieth birthday.[3] Due to Eigtved's death a few months later, final work such as the Banqueting Hall, was completed by Nicolas-Henri Jardin.

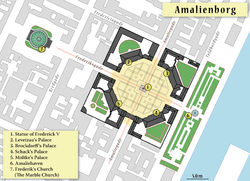

The four palaces are:

- Moltke's Palace, now known as Christian VII's Palace

- Levetzau's Palace, now known as Christian VIII's Palace

- Brockdorff's Palace, now known as Frederick VIII's Palace

- Schack's Palace, now known as Christian IX's Palace

Royal residence

Immediately after the Christiansborg Palace fire in March 1794, and two years after the death of Moltke, the royal family, headed by the schizophrenic King Christian VII, purchased the first of the four palaces to be sold to the royal family, and commissioned Caspar Frederik Harsdorff to turn it into a royal residence. They occupied the new residence December 1794.

After Christian VII’s death in 1808, Frederick VI used the palace for his Royal Household. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs used parts of the Palace in the years 1852–1885. For short periods of time in the intervening years the palace has housed various members of the royal family while restoration took place on their respective palaces. In 1971–1975 a small kindergarten was established at the palace, and later a schoolroom, for Crown Prince Frederik and Prince Joachim.

Restoration

After 200 years the facade, decorated by German sculptor Johan Christof Petzold, was severely damaged, causing parts of Amalienborg Place to be closed to prevent injury. In 1982, exterior and interior restoration began that completed in early 1996, Copenhagen's year as European Capital of Culture. In 1999, Europa Nostra, an international preservation organisation, acknowledged the restoration with by presenting a medal.

Currently, the palace is one of two, along with the Christian VIII's Palace, that is open to the public.

See also

References

- Notes

- The Danish Monarchy & Amalienborg – In and Around Copenhagen and Denmark – Copenhagenet.dk. Retrieved 16 February 2012.

- Lehmann-haupt, Christopher (21 December 1995). "BOOKS OF THE TIMES; That Name Keeps Cropping Up in German History". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- Bain 1911.

- Sources

- H.H. Langhorn, Historische Nachricht über die danischen Moltkes (Kid, 1871).