Misrepresentation

In common law jurisdictions, a misrepresentation is an untrue or misleading [1] statement of fact made during negotiations by one party to another, the statement then inducing that other party to enter into a contract.[2][3] The misled party may normally rescind the contract, and sometimes may be awarded damages as well (or instead of rescission).

The law of misrepresentation is an amalgam of contract and tort; and its sources are common law, equity and statute. The common law was amended by the Misrepresentation Act 1967. The general principle of misrepresentation has been adopted by the USA and various Commonwealth countries, e.g. India.

Representation and contract terms

A "representation" is a pre-contractual statement made during negotiations.[4] If a representation has been incorporated into the contract as a term,[5] then the normal remedies for breach of contract apply. Factors that determine whether or not a representation has become a term include:

- The relative expertise of the parties.[6][7]

- The reliance that one party has shown on the statement.[8]

- The reassurances given by the speaker.[9]

- The customary norms of the trade in question.[10]

- The representation forms the basis of a collateral contract.[11][12][13][14][15][16]

Otherwise, an action may lie in misrepresentation, and perhaps in the torts of negligence and deceit also. Although a suit for breach of contract is relatively straightforward, there are advantages in bringing a parallel suit in misrepresentation, because whereas repudiation is available only for breach of condition[17], rescission is prima facie available for all misreps, subject to the provisions of s.2 of the Misrepresentation Act 1967, and subject to the inherent limitations of an equitable remedy.[18]

Duties of the parties

For a misrepresentation to occur, especially a negligent misrepresentation, the following elements need to be satisfied.

- A positive duty that exists to ascertain and convey the truth to the other contracting party,

- and subsequently a failure to meet that duty, and

- ultimately a harm must arise from that failure.

English contract law

There is no general duty of disclosure in English contract law, and one is normally not obliged to say anything.[19] Ordinary contracts do not require "good faith" as such,[20] and mere compliance with the law is sufficient. However in particular relationships silence may form the basis of an actionable misrepresentation:[21][22]

- Agents have a fiduciary relationship with their principal. They must make proper disclosure and must not make secret profits.[23]

- Employers and employees have a bona fide duty to each other once a contract of employment has begun; but a job applicant owes no duty of disclosure in a job interview.[24][25][26]

- A contract uberrimae fidei is a contract of 'utmost good faith', and include contracts of insurance, business partnerships, and family agreements.[27] When applying for insurance, the proposer must disclose all material facts for the insurer properly to assess the risk.[28][29][30][31] In the UK, the duty of disclosure in insurance has been substantially amended by the Insurance Act 2015.

The "untrue statement"

To amount to a misrepresentation, the statement must be untrue or seriously misleading.[1] A statement which is "technically true" but which gives a misleading impression is deemed an "untrue statement".[32][33] If a misstatement is made and later the representor finds that it is false, it becomes fraudulent unless the representer updates the other party.[34] If the statement is true at the time, but becomes untrue due to a change in circumstances, the representor must update the original statement.[35][36] Actionable misrepresentations must be misstatements of fact or law:[37][38] misstatements of opinion[39] or intention are not deemed statements of fact;[40][33] but if one party appears to have specialist knowledge of the topic, his "opinions" may be considered actionable misstatements of fact.[41][42] For example, false statements made by a seller regarding the quality or nature of the property that the seller has may constitute misrepresentation.[43]

- Statements of opinion

Statements of opinion are usually insufficient to amount to a misrepresentation[38] as it would be unreasonable to treat personal opinions as "facts", as in Bisset v Wilkinson.[44]

Exceptions can arise where opinions may be treated as "facts":

- where an opinion is expressed yet this opinion is not actually held by the representor,[38]

- where it is implied that the representor has facts on which to base the opinion,[45]

- where one party should have known facts on which such an opinion would be based.[46]

- Statements of intention

Statements of intention do not constitute misrepresentations should they fail to come to fruition, since the time the statements were made they can not be deemed either true or false. However, an action can be brought if the intention never actually existed, as in Edgington v Fitzmaurice.[47]

- Statements of law

For many years, statements of law were deemed incapable of amounting to misrepresentations because the law is "equally accessible by both parties" and is "...as much the business of the plaintiff as of [the defendants] to know what the law [is].".[48] This view has changed, and it is now accepted that statements of law may be treated as akin to statements of fact.[49] As stated by Lord Denning "...the distinction between law and fact is illusory".[50]

- Statement to the misled

An action in misrepresentation can only be brought by the misled party, or "representee". This means that only those who were an intended recipient of the representation may sue, as in Peek v Gurney,[51] where the plaintiff sued the directors of a company for indemnity. The action failed because it was found that the plaintiff was not a representee (an intended party to the representation) and accordingly misrepresentation could not be a protection.

It is not necessary for the representation to have been be received directly; it is sufficient that the representation was made to another party with the intention that it would become known to a subsequent party and ultimately acted upon by them.[52] However, it IS essential that the untruth originates from the defendant.

Inducement

The misled party must show that he relied on the misstatement and was induced into the contract by it.

In Attwood v Small,[53] the seller, Small, made false claims about the capabilities of his mines and steelworks. The buyer, Attwood, said he would verify the claims before he bought, and he employed agents who declared that Small's claims were true. The House of Lords held that Attwood could not rescind the contract, as he did not rely on Small but instead relied on his agents. Edgington v Fitzmaurice[54] confirmed further that a misrepresentation need not be the sole cause of entering a contract, for a remedy to be available, so long as it is an influence.[55][56][57][58]

A party induced by a misrepresentation is not obliged to check its veracity. In Redgrave v Hurd [59] Redgrave, an elderly solicitor told Hurd, a potential buyer, that the practice earned £300 pa. Redgrave said Hurd could inspect the accounts to check the claim, but Hurd did not do so. Later, having signed a contract to join Redgrave as a partner, Hurd discovered the practice generated only £200 pa, and the accounts verified this figure. Lord Jessel MR held that the contract could be rescinded for misrepresentation, because Redgrave had made a misrepresentation, adding that Hurd was entitled to rely on the £300 statement.[60]

By contrast, in Leaf v International Galleries,[61] where a gallery sold painting after wrongly saying it was a Constable, Lord Denning held that while there was neither breach of contract nor operative mistake, there was a misrepresentation; but, five years having passed, the buyer's right to rescind had lapsed. This suggests that, having relied on a misrepresentation, the misled party has the onus to discover the truth "within a reasonable time". In Doyle v Olby [1969],[62] a party misled by a fraudulent misrepresentation was deemed NOT to have affirmed even after more than a year.

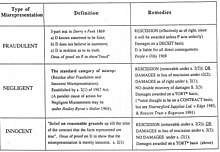

Innocent misrepresentation, negligent misrepresentation, fraudulent misrepresentation

Australian law

Within trade and commerce, the law regarding misrepresentation is dealt with by the Australian Consumer Law, under Section 18 and 29 of this code, the ACL calls contractual misrepresentations as "misleading and deceptive conduct" and imposes a prohibition. The ACL provides for remedies, such as damages, injunctions, rescission of the contract, and other measures.[63]

English law

In England, the common law was codified and amended by the Misrepresentation Act 1967. (Although short and apparently succinct, the 1967 Act is widely regarded as a confusing and poorly drafted statute which has caused a number of difficulties, especially in relation to the basis of the award of damages.[64] It was mildly amended by the Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977 and in 2012, but it escaped the attention of the consolidating Consumer Rights Act 2015).

Prior to the Misrepresentation Act 1967, the common law deemed that there were two categories of misrepresentation: fraudulent and innocent. The effect of the act is primarily to create a new category by dividing innocent misrepresentation into two separate categories: negligent and "wholly" innocent; and it goes on to state the remedies in respect of each of the three categories.[65] The point of the three categories is that the law recognises that the defendant may have been blameworthy to a greater or lesser extent; and the relative degrees of blameworthiness lead to differing remedies for the claimant.

Once misrepresentation has been proven, it is presumed to be "negligent misrepresentation", the default category. It then falls to the claimant to prove that the defendant's culpability was more serious and that the misrepresentation was fraudulent. Conversely, the defendant may try to show that his misrepresentation was innocent.

- Negligent misrepresentation is simply the default category.[66]

- Remedy: The misled party may rescind and claim damages under s.2(1) for any losses. The court may "declare the contract subsisting" and award damages in lieu of rescission, but s.2(3) prevents the award of double damages.

- Fraudulent misrepresentation is defined in the 3-part test in Donohoe v Donohoe , where the defendant Donohoe was categorically declared completely fraudulent as he:

- (i) knows the statement to be false,[67] or

- (ii) does not believe in the statement,[68][38] or

- (iii) is reckless as to its truth.

- Remedy: The misled party may rescind and claim damages for all directly consequential losses. Doyle v Olby [1969]

- Innocent misrepresentation is "belief on reasonable grounds up till the time of the contract that the facts represented are true". (s.2(1)of the Act).

- Remedy: The misled party may rescind but has no entitlement to damages under s.2(1). However, the court may "declare the contract subsisting" and award damages in lieu of rescission.[69] (By contrast, the victim of a breach of warranty in contract may claim damages for loss, but may not repudiate)[70]

Negligent misstatement

Negligent misstatement is not strictly part of the law of misrepresentation, but is a tort based upon the 1964 obiter dicta in Hedley Byrne v Heller [71] where the House of Lords found that a negligently-made statement (if relied upon) could be actionable provided a "special relationship" existed between the parties.[72]

Subsequently in Esso Petroleum Co Ltd v Mardon,[73] Lord Denning transported this tort into contract law, stating the rule as:

...if a man, who has or professes to have special knowledge or skill, makes a representation by virtue thereof to another…with the intention of inducing him to enter into a contract with him, he is under a duty to use reasonable care to see that the representation is correct, and that the advice, information or opinion is reliable'.

Remedies

Depending on the type of misrepresentation, remedies such as recission, or damages, or a combination of both may be available. Tortious liability may also be considered. Several countries, such as Australia have a statutory schema which deals with misrepresentations under consumer law.[74]

- Innocent misrepresentation

Entitlement to rescission of the contract, but not damages

- Negligent misrepresentation

Entitlement to damages or rescission of the contract

- Fraudulent misrepresentation

Entitlement to damages, or rescission of the contract

Rescission

A contract vitiated by misrepresentation is voidable and not void ab initio. The misled party may either (i) rescind, or (ii) affirm and continue to be bound. If the claimant chooses to rescind, the contract will still be deemed to have been valid up to the time it was avoided, so any transactions with a third party remains valid, and the third party will retain good title.[75] Rescission can be effected either by informing the representor or by requesting an order from the court. Rescission is an equitable remedy which is not always available.[76] Rescission requires the parties to be restored to their former positions; so if this is not possible, rescission is unavailable.[77]

A misled party who, knowing of the misrepresentation, fails to take steps to avoid the contract will be deemed to have affirmed through "laches", as in Leaf v International Galleries;[78][79][80] and the claimant will be estopped from rescinding. The time limit for taking such steps varies depending on the type of misrepresentation. In cases of fraudulent misrepresentation, the time limit runs until when the misrepresentation ought to have been discovered, whereas in innocent misrepresentation, the right to rescission may lapse even before the represent can reasonably be expected to know about it.[81]

Sometimes, third party rights may intervene and render rescission impossible. Say, if A misleads B and contracts to sell a house to him, and B later sells to C, the courts are unlikely to permit rescission as that would unfair impinge upon C.

Under Misrepresentations Act 1967 s. 2(2) of the Misrepresentation Act 1967, the court has discretion to award damages instead of rescission, "if of opinion that it would be equitable to do so, having regard to the nature of the misrepresentation and the loss that would be caused by it if the contract were upheld, as well as to the loss that rescission would cause to the other party."

Damages

"Damages" are monetary compensation for loss. In contract[82] and tort,[83] damages will be awarded if the breach of contract (or breach of duty) causes foreseeable loss.

- By contrast, a fraudulent misrepresenter is liable in the common law tort of deceit for all direct consequences, whether or not the losses were foreseeable.[84]

- For negligent misrepresentation, the claimant may get damages as of right under s.2(1) and/or damages in lieu of rescission under s.2(2).

- For innocent misrepresentation, the claimant may get only damages in lieu of rescission under s.2(2).

Given the relative lack of blameworthiness of a non-fraudulent defendant (who is at worst merely careless, and at best may honestly "believe on reasonable grounds" that he told the truth) for many years lawyers presumed that for these two categories, damages would be on a contract/tort basis requiring reasonable foreseeability of loss.

In 1991, Royscot Trust Ltd v Rogerson[85] changed all that. The court gave a literal interpretation of s.2 (which, to paraphrase, provides that where a person has been misled by a negligent misrepresentation then, if the misrepresentor would be liable to damages had the representation been made fraudulently, the defendant "shall be so liable"). The phrase shall be so liable was read literally to mean "liable as in fraudulent misrepresentation". So, under the Misrepresentation Act 1967, damages for negligent misrepresentation are calculated as if the defendant had been fraudulent, even if he has been merely careless.[86] Although this was almost certainly not the intention of Parliament, no changes to the law have been made to address this discrepancy: the Consumer Rights Act 2015 left the 1967 Act intact. This is known as the fiction of fraud and also extends to tortious liability.[87]

S.2 does not specify how "damages in lieu" should be determined, and interpretation of the statute is up to the courts.

Vitiating factors

| Contract law |

|---|

|

| Part of the common law series |

| Contract formation |

| Defenses against formation |

| Contract interpretation |

| Excuses for non-performance |

| Rights of third parties |

| Breach of contract |

| Remedies |

| Quasi-contractual obligations |

| Related areas of law |

| Other common law areas |

Misrepresentation is one of several vitiating factors that can affect the validity of a contract. Other vitiating factors include:

See also

- Embezzlement

- False pretenses—related criminal law term

- Tort of deceit

Bibliography

- Books and chapters

- PS Atiyah, Introduction to the Law of Contract (4th edn Clarendon, Oxford 1994)

- H Beale, Bishop and Furmston, Cases and Materials on Contract Law (OUP 2008)

- A Burrows, Cases and Materials on Contract Law (2nd edn Hart, Oxford 2009) ch 11

- H Collins, Contract law in context (4th edn CUP, Cambridge 2004)

- E McKendrick, Contract Law (8th edn Palgrave, London 2009) ch 13

- E Peel, Treitel: The Law of Contract (7th edn Thompson, London 2008) ch 9

- M Chen-Wishart, Contract Law (6th edn OUP 2018) ch 5

- Articles

- PS Atiyah and G Treitel, 'Misrepresentation Act 1967' (1967) 30 MLR 369

- PS Atiyah, 'Res Ipsa Loquitur in England and Australia' (1972) 35 Modern Law Review 337

- R Taylor, 'Expectation, Reliance and Misrepresentation' (1982) 45 MLR 139

- R Hooley, 'Damages and the Misrepresentation Act 1967' (1991) 107 LQR 547,[88]

- I Brown and A Chandler, 'Deceit, Damages and the Misrepresentation Act 1967, s 2(1)' [1992] LMCLQ 40

- H Beale, ‘Damages in Lieu of Rescission for Misrepresentation’ (1995) 111 LQR 60

- J O'Sullivan, 'Rescission as a Self-Help Remedy: a Critical Analysis' [2000] CLJ 509

- W Swadling, ‘Rescission, Property and the Common law’ (2005) 121 LQR 123, suggests the reasoning on recovery of property should not merge the issues of validity of contract and transfer of title.[89]

- B Häcker, ‘Rescission of Contract and Revesting of Title: A Reply to Mr Swadling’ [2006] RLR 106, responds to Swadling's argument. She point out flaws in Swadling's (1) historical analysis; and (2) conceptual analysis.

- J Cartwright, 'Excluding Liability for Misrepresentation' in A Burrows and E Peel, Contract Terms (2007) 213

References

- R v Kylsant [1931]

- In Curtis v Chemical Cleaning and Dyeing Co[1951] Ms Curtis took a wedding dress with beads and sequins to the cleaners. They gave her a contract to sign and she asked the assistant what it was. The assistant said it merely covered risk to the beads, but in fact the contract exempted all liability. The dress was stained but the exclusion was ineffective because of the assistant's misrepresentation, and the claim was allowed.

- Curtis v Chemical Cleaning and Dyeing Co [1951] 1 KB 805

- For the purposes of "offer and acceptance", a representation may serve a further function such as an "offer", "counter-offer", "invitation to treat", "request for information" or "statement of intention"

- A contractual term may be a warranty, condition or innominate term.

- Oscar Chess v Williams (1957)

- Dick Bentley v Harold Smith Motors (1965)

- Bannerman v White (1861).

- Schawel v Reade (1913)

- Ecay v Godfrey (1947)

- Andrews v Hopkinson (1957)

- Shanklin Pier v Detel Products (1951)

- Evans v Andrea Merzario (1976)

- Heilbut, Symons & Co. v Buckleton [1913] A.C. 30 HL

- Hoyt's Pty Ltd v Spencer [1919]

- [1919] HCA 64, High Court (Australia).

- A "condition" is a term whose breach denies the main benefit of the contract to the claimant.

- "Inherent limitations": equitable remedies are only ever discretionary; and one must "come to equity with clean hands".

- However, EU Law has introduced a "right of reasonable expectation". - Marleasing

- "Good faith in English contract law?"

- Hospital Products Ltd v United States Surgical Corp [1984] HCA 64, (1984) 156 CLR 41 at [68], High Court (Australia).

- See, e.g., Davies v. London & Provincial Marine Insurance Co (1878) 8 Ch. D. 469, 474. Justice Fry commented on the responsibilities of a fiduciary "...they can only contract after the most ample disclosure of everything..."

- Lowther v Lord Lowther (1806) 13 Ves Jr 95, the plaintiff handed over a picture to an agent for sale. The agent knew of the picture's true worth yet bought it for a considerably lower price. The plaintiff subsequently discovered the picture's true worth and sued to rescind the contract. It was held that the defendant was in a fiduciary relationship with the plaintiff and accordingly assumed an obligation to disclose all material facts. Accordingly, the contract could be rescinded.

- In Fletcher v Krell (1873) 2 LJ (QB) 55, a woman who was appointed to the post of governess failed to reveal that she had previously been married. (The employer favoured single women). It was held that she had made no misrepresentation.

- Spice Girls v Aprilia World Service CHD 24 FEB 2000

- http://swarb.co.uk/spice-girls-ltd-v-aprilia-world-service-bv-chd-24-feb-2000/

- Gordon v Gordon (1821) 3 Swan 400, two brothers had reached an agreement regarding the family estate. The elder brother was under the impression that he was born out of wedlock and thus not their father's true heir. The agreement was reached on this basis. The elder brother subsequently discovered that this was not the case and that the younger brother had knowledge of this during the negotiation of the settlement. The elder brother sued to set aside the agreement and was successful on the grounds that such a contract was one of uberrimae fidei and the required disclosure had not been executed.

- In insurance the insurer agrees to indemnify the assured against losses proximately caused by insured perils, and the insurer is thus entitled to know full details of the risk being transferred to him.

- Lord Blackburn addressed the issue in Brownlie v Campbell (1880) 5 App Cas 925 when he noted "...the concealment of a material circumstance known to you...avoids the policy."

- In the 1908 case of Joel v Law Union [1908] KB 884 the de minimis rule was applied in a life assurance policy. Despite minor omissions, the assured had made a sufficiently substantial disclosure of material facts that the insurer knew the risk, and the policy was valid

- lex non curat de minimis - the law does not concern itself with trifles

- In Krakowski v Eurolynx Properties Ltd, Krakowski agreed to enter into a contract to buy a shop premises from Eurolynx as long as a 'strong tenant' had been organised. The contract proceeded on the grounds that such a tenant had been arranged. Unbeknown to Krakowski, Eurolynx had entered into an additional agreement with the tenant to provide funds for the first three months rent to ensure the contract went ahead. When the tenant defaulted on the rent and subsequently vacated the premises, Krakowski found out about the additional agreement and rescinded the contract with Eurolynx. It was held that Eurolynx's failure to disclose all material facts about the 'strong tenant' was enough to constitute a misrepresentation and the contract could be rescinded on these grounds.

- Krakowski v Eurolynx Properties Ltd [1995] HCA 68, (1995) 183 CLR 563, High Court (Australia).

- Lockhart v. Osman [1981] VR 57, an agent had advertised some cattle as being "well-suited for breeding purposes". Later on, it was discovered that the stock had been exposed to a contagious disease which affected the reproductive system. It was held that the agent had a duty to take remedial action and correct the representation. The failure by the agent to take such measures resulted in the contract being set aside.

- With v O'Flanagan [1936] Ch. 575, the plaintiff entered into a contract to purchase O'Flanagan's medical practice. During negotiations it was said that the practice produced an income of £2000 per year. Before the contract was signed, the practice took a downward turn and lost a significant amount of value. After the contract had been entered into, the true nature of the practice was discovered and the plaintiff took action in misrepresentation. In his decision, Lord Wright said, "...a representation made as a matter of inducement to enter into a contract is to be treated as a continuing representation.".

- With v O'Flanagan [1936] Ch. 575, 584.

- Kleinwort Benson Ltd v Lincoln City Council [1999] 2 AC 349, abolished a bar on mistake of law bar and Pankhania v Hackney LBC [2002] EWHC 2441 (Ch) held the same went for misrepresentation under Misrepresentation Act 1967 s 2(1) where agents of a land seller incorrectly said that people running a car park on some property were licensees rather than protected business tenants

- Fitzpatrick v Michel [1928] NSWStRp 19, Supreme Court (NSW, Australia).

- Bisset v Wilkinson [1927] AC 177 PC

- See Achut v Achuthan [1927] AC 177.

- See Esso Petroleum Co Ltd v Mardon [1976] 2 Lloyd's Rep 305.

- Smith v Land & House Property (1884) 28 Ch D 7 CA

- Smith v Land & House Property (1884) 28 Ch D 7 CA

- Bisset v Wilkinson [1927] AC 177.

- See, e.g., Smith v Land & House Property Corp (1884) 28 Ch. D. 7.

- See, e.g., Esso Petroleum v Mardon [1976] QB 801.

- In Edgington v Fitzmaurice (1885) 29 Ch. D. 459, company directors seeking a loan "intended to develop the business" always intended to use the cash to repay debts. The state of mind is an existing fact, therefore, a false presentation of an existing fact, so that the contract was voidable.

- Beattie v Lord Ebury (1872) LR 7 Ch App 777, 803.

- See, e.g., David Securities Pty Ltd v Commonwealth Bank of Australia [1992] HCA 48, (1992) 175 CLR 353, High Court (Australia); see also Public Trustee v Taylor [1978] VicRp 31, Supreme Court (Vic, Australia). While dealing with a mistake of law, similar reasoning should apply to a misrepresentation of law.

- Andre & Cie v Ets Michel Blanc & Fils [1979] 2 Lloyds LR 427, 430.

- Peek v Gurney (1873) LR 6 HL 377

- See, e.g., Commercial Banking Co (Sydney) Ltd v R H Brown & Co [1972] HCA 24, (1972) 126 CLR 337, High Court (Australia).

- (1838) 6 Cl&F 232

- (1885) 29 Ch D 459

- A Burrows, A Casebook on Contract (Hart, Oxford 2007) 355

- Standard Chartered Bank v Pakistan National Shipping Corp (No 2) [2002] UKHL 43, damages for deceit cannot be reduced for contributory negligence.

- Gran Gelato Ltd v Richcliff (Group) Ltd [1992] QB 560

- see Smith v Hughes (1871) LR 6 QB 597

- (1881) 20 Ch D 1

- The case also makes clear that, the circumstances having altered, Redgrave was under a duty to inform the Hurd of the changes.

- Leaf v International Galleries [1950] 2 KB 86

- Doyle v Olby1969 2 QB 158 CA

- https://www.artslaw.com.au/images/uploads/NEW_ACL_and_other_legal_actions_07.01.2016.pdf

- Royscot Trust Ltd v Rogerson [1991] 2 QB 297

- Nowhere in the 1967 Act are the words "negligent misrepresentation" to be found; that terminology was established by practising and academic lawyers.

- There is no specific relationship between negligent misrepresentation and the tort of negligence and the duty of care under Donoghue v Stevenson or Hedley Byrne v Heller.

- R v Kylsant

- A defendant honestly believing his statement to be true is not fraudulent: "Honesty of belief in the truth of a warranty is no defence to a breach of warranty, whereas it is a complete defence to a charge of false representation. If a statement is an honest expression of opinion, honestly entertained, it cannot be said that it involves a fraudulent misrepresentation of fact."

- The victim of an innocent misrepresentation who wishes to affirm the contract has no legal right to damages. Of course, the misled party may seek to negotiate a compensation payment, but the other party need not comply; and if the misled party litigates to seek "damages in lieu", but the court holds that the contract must subsist, the misled party will lose the case and be liable for costs.

- Hong Kong Fir Shipping v Kawasaki Kisen Kaisha

- Hedley Byrne v Heller [1964] A.C. 465

- In Hedley Byrne v Heller, the "special relationship" was between one bank who gave a financial reference to another bank.

- Esso Petroleum Co Ltd v Mardon [1976] Q.B. 801

- http://www.comlaw.gov.au/Details/C2011C00003/Html/Volume_3#param46

- For legal reasoning application of the difference see Shogun Finance Ltd v Hudson [2004] 1 AC 919; Brooks, O & Dodd, A ‘Shogun: A Principled Decision’ (2003) 153 NLJ 1898

- "He who comes to equity must come with clean hands".

- See Erlanger v New Sombrero Phosphate Co (1878) 3 App. Cas. 308.

- Leaf v International Galleries 1950] 2 KB 86

- See Long v. Lloyd [1958] 1 WLR 753. See also Alati v Kruger [1955] HCA 64, High Court (Australia).

- in Long v Lloyd Mr Long bought from Mr Lloyd a lorry advertised as being in ‘exceptional condition,’ said to do 40 mph and 11 miles to the gallon. When it broke down after two days and was doing 5 miles to the gallon, Mr Long complained. Mr Lloyd said he would repair it for half the price of a reconstructed dynamo. Because Mr Long accepted this, when it broke down again, Pearce LJ held the contract had been affirmed. It was too late to escape for misrepresentation. A more lenient approach may now exist. As Slade LJ pointed out in Peyman v Lanjani,[42] actual knowledge of the right to choose to affirm a contract or rescind is essential before one can be said to have "affirmed" a contract.

- See Leaf v International Galleries [1950] 2 KB 86.

- Hadley v Baxendale

- The Wagon Mound

- Doyle v Olby (Ironmongers) Ltd [1969] 2 QB 158]

- Royscott Trust v Rogerson [1991] 3 All ER 294 CA

- Royscott Trust v Rogerson is arguably per incuriam as the court failed to pay attention to the definition of fraudulent misrep in Derry v Peek. Had the court done so, it would have held that the misrep in this case was fraudulent rather than negligent.

- Tortious liability has a wider scope than usual contractual liability, as it allows the claimant to claim for loss even if it is not reasonably foreseeable, which is not possible with a claim for breach of contract due to the decision in Hadley v Baxendale. Inclusion of the representation into the contract as a term will leave the remedy for breach in damages as a common law right. The difference is that damages for misrepresentation usually reflect the claimant's reliance interest, whereas damages for breach of contract protect the claimant's expectation interest, although the rules on mitigation will apply in the latter case. In certain cases though, the courts have awarded damages for loss of profit, basing it on loss of opportunity: see East v Maurer [1991] 2 All ER 733.

- Hooley argues that fraud and negligence are qualitatively different and should be treated differently in order to reflect fraud's greater moral culpability. He says the Misrepresentation Act 1967 s 2(1) establishes only liability in damages but not their quantum, so Royscott was a poor decision.

- Swadling controversially says the two are separate (i.e. he is in favour of the ‘abstraction principle’). So Caldwell should not have got his car back. Rights in property are passed on delivery and with intent to pass title. This is not dependent on the validity of the contract. In short, he argues for the abstraction principle.