Ministry of Industry (Japan)

The Ministry of Public Works (工部省, Kōbushō) was a cabinet-level ministry in the Daijō-kan system of government of the Meiji period Empire of Japan from 1870-1885. It is also sometimes referred to as the “Ministry of Engineering” or “Ministry of Industry”.[1]

History

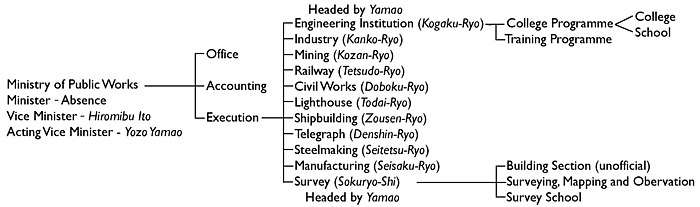

The Cabinet officially announced the establishment of the Public Works on December 12, 1870 by the advice of Edmund Morel, chief engineer of the Railway Construction to achieve rapid social and industrial development. After long arguments of 10 months, in September 28, 1871, the Meiji government completed arrangement of organization of 11 departments, which were mostly transferred from the Ministry of Civil Affairs. It included railroads, shipyards, lighthouses, mines, an iron and steel industry, telecommunication, civil works, manufacturing, industrial promotion, engineering institution and survey[2]. Each department had to be relied on the foreign advisor and officer for a while[3], but gradually replaced them with Japanese engineers, who received training in the Engineering Institution. Main function of the Engineering Institution was to manage the Imperial College of Engineering (the predecessor of the Tokyo Imperial University College of Engineering). One of the key roles of the ministry was locating, and if necessary, reverse engineering overseas technology. For example, in 1877, only a year after the invention of the telephone, engineers employed by the ministry had obtained examples and were attempting to create a domestic version.[4] By the mid-1880s, many of the industries created by the Ministry of Industry were privatized. With the establishment of the cabinet system under the Meiji Constitution on December 22, 1885, the ministry was abolished, with its functions divided between the new Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce and the Ministry of Communications.

| Name | Kanji | in office | out of office |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minister (工部卿, Kōbu-kyō) | |||

| Itō Hirobumi | 伊藤 博文 | October 25, 1873 | May 15, 1878 |

| Inoue Kaoru | 井上 馨 | July 29, 1878 | September 10, 1879 |

| Yamada Akiyoshi | 山田 顕義 | September 10, 1879 | February 28, 1880 |

| Yamao Yōzō | 山尾 庸三 | February 28, 1880 | October 21, 1881 |

| Sasaki Takayuki | 佐々木 高行 | October 21, 1881 | December 22, 1885 |

| Vice-Minister (工部大輔, Kōbu-taifu) | |||

| Yamao Yōzō | 山尾 庸三 | October 27, 1872 | February 28, 1880 |

| Yoshii Tomozane | 吉井 友実 | June 17, 1880 | January 10, 1882 |

| Inoue Masaru | 井上 勝 | July 8, 1882 | December 22, 1885 |

References

- Smith, Thomas Carlyle (1955). Political Change and Industrial Development in Japan. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-0469-4.

- Nelson, Richard R (1993). National Innovation Systems : A Comparative Analysis: A Comparative Analysis. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-536043-5.

- Fukasaku, Yukiko (2013). Technology and Industrial Growth in Pre-War Japan:. Routledge. ISBN 1-134-96401-3.

- Morris-Suzuki, Teresa (1994). The Technological Transformation of Japan. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-42492-5.

Notes

- Morris-Suzuki. The Technological Transformation of Japan. page 73.

- Hideo Izumida: Reconsideration of Foundation of Ministry of Public Works, Transaction of Japan Institution of Architecture, 2016.

- Fukasaku. Technology and Industrial Growth in Pre-War Japan. Pages 18, 40

- Nelson. National Innovation Systems. Page 95

- "太政官時代". Archived from the original on 2012-07-10. Retrieved 2014-01-09.