Mind-blindness

Mind-blindness is a concept of a cognitive divergence where an individual is unable to attribute mental states to others. As a result of this kind of social[1] and empathetic cognitive phenomenon, the individual is incapable of putting themselves "into someone else's shoes" and cannot conceptualize, understand or predict knowledge, thoughts and beliefs, emotions, feelings and desires, behaviour, actions and intentions of another person.[2] Such an ability to develop a mental awareness of what is in the other minds is known as the theory of mind (ToM),[3] and the "mind-blindness" theory asserts that children who delay in this development often will develop autism.[4][5] In addition to the research done on autism, ToM and mind-blindness research has recently been extended to other fields such as schizophrenia, dementia, bipolar disorders, antisocial personality disorders as well as normal aging.[6]

Relevance and causes

Theory of mind

Mind-blindness is a state where the ToM has not been developed, or has been lost in an individual. According to the theory, ToM is implicit in neurotypical individuals. This enables one to make automatic interpretations of events taking into consideration the mental states of people, their desires and beliefs. Simon Baron-Cohen described how an individual lacking a ToM would perceive the world in a confusing and frightening manner, leading to a withdrawal from society.[7] Since Cohen’s opinion was based on the idea that biology is strictly linked to autistic behavior, he started wondering if a delayed development of the theory of mind would lead to additional psychiatric complications. Moreover, he wondered if there exist multiple degrees of mental blindness.[8]

An alternative approach to the social impairment observed in mind-blindness focuses on the emotion of subjects. Based on empirical evidence, Uta Frith concluded that the processing of complex cognitive emotions is impaired compared to simpler emotions. In addition, attachment does not seem to fail in the early childhood of autistics. This suggests that emotion is a component of social cognition that is separable from mentalizing.[1]

Lombardo and Cohen updated the theory and pinpointed some additional factors that play an important part in ToM of autistic people. They highlighted that the middle cingulate cortex which is outside the traditional mentalizing region was underactive in autistic patients, while the rest of ToM activation was normal. This region was important in deciding how much to invest in a person and hence required mentalization.[9]

Theory of Mind in children

Scholars have recently wondered if children do possess a theory of mind. Specifically, Wellman and others have wondered if the theory of mind that characterizes adults is somehow different from the one that characterizes children.[10] According to the studies conducted by Wellman, children starting from three years of age, do possess a theory of mind.[10] Wellman is not the only scholar who was interested in discovering about the theory of mind and its divergent characteristics that effect both children and adults. Indeed, scholar Wang, in her work Mindful learning: Children’s developing theory of mind and their understanding of the concept of learning argues that the “theory of mind development is critical for children to engage in mindful learning, which refers to the learning during which the learner is consciously aware of own mental states and the changes in them, both motivational and epistemic mental states”.[11] Wang was able to demonstrate that children develop theory of mind as they understand how to conceptualize learning.[11] Indeed, Wang argued, during preschool years children become able to consider learning as the “representational knowledge change in the mind”.[11]

Additionally, Wang was also able to demonstrate that children that belong to divergent cultures develop theory of mind in different ways. Al-Hilawani, Easterbrooks, and Marchant (2002), who tried to understand the phenomenon regarding the development of the theory of mind in children from different cultures, reported that children with hearing loss, and therefore children who could potentially have problems developing the theory of mind, are “similar to hearing children in their ability to learn and reason if they are from the same culture, but not necessarily if the two groups of students are from different cultures”.[12]

Biological basis

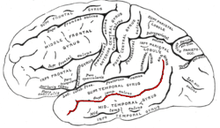

Neural correlates of the ToM point towards three regions of the brains. The anterior paracingulate cortex (Brodmann), is considered at the key region of mentalizing. It is located anterior corpus callosum and the anterior cingulate cortex. This cortex is associated with the medial frontal cortex where activation is associated with the mentalization of states. The cells of the ACC develops at the age of 4 months suggesting that the manifestations of mind-blindness may occur around this time.[2]

In addition to the anterior paracingulate cortex, there is the superior temporal sulcus and the temporal poles that are involved with the ToM and its nature. However, these areas are not uniquely associated with mentalization. They aid in the activation of the regions that are associated with the ToM. The superior temporal sulcus is therefore involved in the processing of behavioural information, while the temporal poles are involved in the retrieval of personal experiences. These are considered important regions for the activation of the ToM regions and are associated with the mind-blindness. The temporal poles provide personal experiences for mentalization such as facial recognition, emotional memory and familiar voices. In patients suffering from semantic dementia, for example, the temporal regions of these patients undergo atrophy and lead to certain deficits which can cause mind-blindness.[2]

The amygdala and the orbitofrontal cortex also are a part of the ToM. Those mental structures seem to be involved in the interpretation of behavior. It is suspected, in fact, that the damage to the orbitofrontal cortex brings upon subtle impairments, but not a total loss of the ToM that would lead to mind-blindness.[2] Some studies have shown that the orbitofrontal cortex is not directly associated with the theory of the mind or mind-blindness. However, a study by Stone and colleagues were able to show impaired ToM on mentalisation tasks.[13]

Surely, as reported by Gallagher and Firth (2003), neuroimaging plays a significant role “in determining the precise functions of the neural substrates comprising […] the mechanisms underlying theory of mind.” [14] The question that now remains unanswered is if the amygdala and the orbital frontal cortex do play a role in the acquisition of the theory of mind or not.

Since the frontal lobe is associated with executive function, researchers theorize that the frontal lobe plays an important role in ToM and its associated nature. It has also been suggested that the executive function and the theory of mind share the same regions.[15] Despite the fact that ToM and mind-blindness can explain executive function deficits, it is argued that autism is not identified with the failure of the executive function.[16]

Lesion studies show that when lesions are imposed to the medial frontal lobe, performance on mentalization tasks is reduced, similar to typical mind-blindness cases.[17] Patients that experienced frontal lobe injuries due to severe head trauma showed signs of mind blindness, as a result of a lost ToM. However, it is still debated whether the inactivation of the medial frontal lobe is involved in mind-blindness.[18]

Frith proposed that a neural network that comprised the medial prefrontal cortex, the anterior cingulate cortex and the STS, is crucial for the normal functioning of ToM and self monitoring. This so formed dorsal system is crucial for social cognition. Disruption of this neural network leads to mind-blindness in schizophrenic individuals.[19]

Another element that might give a possible explanation of mind-blindness in people with autism was discussed by Castelli and colleagues. For instance, they were able to show that the connectivity between occipital and the temporo-parietal regions were weaker in the autistic group than the control group. The under activation of this network may inhibit the interactive influences between regions that process higher and lower perceptual items.[1]

Relationship to autism

Individuals with autism tend to experience episodes of mind blindness.

According to the psychologist Uta Frith, individuals with social and communication impairments, such as who is affected by autism, will experience difficulties in the process of attributing mental states, as desires and beliefs, to themselves or to others.[20] In her article Mind Blindness and Brain in Autism, Frith discusses the differences between mind reading and mind blindness, and how those phenomena are experienced in the mind of a person with autism. Additionally, Frith affirms that individuals that are affected by autism, have “occasionally commented on what they perceive as an unfathomable yet ubiquitous ability of other people to “mind read” during ordinary social interactions. Normal people indeed behave as if they have an implicit theory of mind, and this allows them to explain and predict others’ behavior in terms of their presumed thoughts and feelings”.[20]

To contrast this idea, Carruthers, in his book Theories of Mind, explains that people affected by autism have more issues than just those argued by the theory of mind, and that those issues do not exclusively involve predicting other individuals’ behavior. Carruthers seems to argue that the “mind-blindness theory has only appeared to be losing out […] , because its proponents have paid insufficient attention to the consequences of their view for the access […] that autistic people will have to their own mental states.” [21]

Moreover, it is important to say that it has been discovered that lower performance on the mentalization tasks were the first screening task used to diagnose the autism, with a good prediction level.[1]

Cohen proposed the mind-blindness theory of autism as "deficits in the normal process of empathising". He described empathising to include the ToM, mind reading and taking an intentional stance. According to this view, empathising includes the ability to attribute mental states and to react in an appropriate emotional manner that is appropriate to another's mental state. More deficits tend to occur in reference to one's own mental states compared to the other's mental states. It has been proposed that individuals affected by autism undergo a specific developmental delay in the area of metarepresentational development. Such delay has been demonstrate to facilitate mind-blindness.[22]

There is some evidence that suggests that certain patients develop a rudimentary ToM and do not suffer from complete lack of ToM causing mind-blindness.[22] A study by Bowler concluded that mind-blindness and social impairment is not as straightforward as previously thought. Such study, for instance, showed that a complete possession of ToM was not enough to protect from social impairments in individuals affected by autism. Conversely, has been demonstrated that the absence or impairment of the ToM that leads to mind-blindness does not lead to social impairments.[23]

The social and cognitive differences seen in individuals affected by autism are often attributed to mind blindness. Abnormal behaviour of autistic children is therefore perceived to include a lack of reciprocity. Some cases in which mind-blindness is manifested, could include the child being totally withdrawn from social settings as well as the child's incapacity to make eye contact, while he or she may instead attempt to interact with other people. However, global asocial behaviour is not the rule in autism. Cohen described the cognitive/mind-blindness effects in individuals diagnosed with autism as a "triad of deficits." The triad consists of deficits in social, communication and imagination of others' minds.[22]

Ozonoff and colleagues were able to discriminate between individuals diagnosed with the Asperger's syndrome and other individuals affected with autism by their ability to solve ToM tasks. This was possible because those diagnosed with AS seem more neurotypical in early childhood development. The siblings of individuals diagnosed with AS were shown to have a lesser variant of ToM deficits. This shows that the cognitive deficits affecting ToM play a central role in the phenotype expressed in AS diagnoses.[24] However, since today’s perceptive about autism and Asperger disorder has changed, Ozonoff research might no longer be considered among other scholars. In fact, the DSM 5 no longer presents the differences between autism and Asperger disorder. Autism is now referred to Spectrum Disorder (ASD), and there are no more differences between all of the subcategories of such disorder. Such subcategories include Asperger syndrome, pervasive developmental disorder, and disintegrative disorder.[25] Unfortunately, “despite this change in diagnostic criteria, the number of diagnosed cases of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is much higher than expected”.[26] As reported by Johnson and Myers (2017), “ASDs are not rare […] In fact, a survey completed in 2004 revealed that 44% of primary care pediatricians reported that they care for at least 10 children with ASDs”.[27]

Relationship to schizophrenia

People with schizophrenia also show deficits associated with mind-blindness.[3] In fact, as stated by Brune, “there is good empirical evidence that the theory of minds is specifically impaired in schizophrenia and that many psychotic symptoms—for instance, delusions of alien control and persecution, the presence of thought and language disorganization, and other behavioral symptoms—may best be understood in light of a disturbed capacity in patients to relate their own intentions to executing behavior, and to monitor others’ intentions.” [28]

However, there is an ongoing debate as to whether individuals with schizophrenia have an impaired ToM leading to mind-blindness or display an exaggerated ToM. Unlike autism, schizophrenia is a late onset condition. It is speculated that this difference in the condition may account for differences seen in the ToM abilities.[29] Brain lesion studies show that there are differences seen in the laterality of brain that account for mind-blindness. However, it is unknown whether the ToM in schizophrenia deteriorates in the affected person as the condition progresses.[6]

The cognitive impairment linked to mind-blindness is best explained by a modular theory; the domain specific capabilities that account for mindreading and mentalization are lost in schizophrenia. Some studies conducted at this regard, have been administrated by Cleghorn and Albert (1990), who strived to understand schizophrenia from multiple angles, such as neurobiology, neuropsychology, and cognitive science. They found that despite “individual modules of cognitive and emotional function may be intact in schizophrenia, messages are inappropriately sent to parts of the brain not specialized for the required information […]thus, “modular disjunction” of widely distributed neural systems develops, causing the signs and symptoms of schizophrenic psychosis.” [30]

Furthermore, Frith has predicted that the extent of mind-blindness depends on whether the objective/behavioural or subjective symptoms of ToM abilities prevail.[1] Patients with the behavioural symptoms perform the poorest in ToM tasks, similar to autistic subjects, while patients displaying subjective/experiential symptoms have a ToM. However, these patients are impaired in using contextual information to infer what these mental states are.[6]

Additionally, it is important to affirm that some scholars have decided to look deeper at Frith’s work and review/ critique her theory. In fact, in their work Theory of mind in schizophrenia: A critical review, Professors Harrington, Siegert, and McClure (2005), have affirmed that the theory proposed by Uta Frith has not few issues that need to be redirected. For instance, “issues that demand further clarification include: Is the deficit a state or a trait? How to measure ToM in schizophrenia research, and whether certain symptoms or groups of symptoms are associated with the ToM deficit".[31]

Criticism

The mind-blindness theory helps to explain the impairment in the social development of individuals as well as the impairment in the communication skills of autistics. However one of the most important limitations of this theory is that it is unable to explain the highly repetitive behaviours which is a characteristic trait attributed to autistic people. This triad is explained through the process of systemising.[22] The theory also did not account for the motor problems and the superior rote memory skills that were associated with autism.[1] These aspects along with the highly repetitive behaviours formed the triad of strengths. Simon Baron-Cohen himself has acknowledged that the theory, while adept at explaining the communications difficulties experienced by autistic people, fails to explain such patients' penchants for narrowly defined interests, an important step to proper diagnosis. Furthermore, mind-blindness seems decidedly non-unique to autistic people, since conditions ranging from schizophrenia to various narcissistic personality disorders and/or anti-social personality disorders all exhibit mind-blindness to some degree.[4]

Another issue associated with the mind-blindness theory is that researchers are unable to predict whether the social deficits are a primary or secondary result of mind-blindness. In addition, Klin and his fellow researchers highlighted another limitation that was that the mind-blindness theory failed to delineate whether the ToM deficits are a generalised deficit or a specific discrete of a mechanism.[32] Stuart Shanker also argued in favour of Klin's argument, that a major part of the mind-blindness theory depicts the ToM as an autonomous cognitive capacity compared to being part of a more general ability for reflective thinking and empathy.[33]

Other researchers have pointed out the inherent flaws of assuming autistic traits develops from a "theory of mind" deficit, pointing out that this presupposes autistic traits derives from a single, core insufficiency within the brain. This contrasts, they say, with the very same researchers' description of autism as a "puzzle", which implies a far more diverse range of causes than a single, unifying theory.[34]

Many have also pointed out that Mind-blindness wrongly categorizes autism as a problem to be fixed, rather than a condition to be accommodated. This assumes an inherent lack of intelligence in individuals affected by autism, which ignores the nuanced view of intelligence (as in varying types of intelligence) that has been observed in cognitive research.[34]

The drawbacks in the Mind-blindness theory of individuals diagnosed with autism paved way for the E-S theory which helps to explain the observations seen in these individuals. The E-S theory accounts for both the triad of deficits which is the loss of empathising and the triad of strengths is related to hyper systemisation of certain behaviours. The theory also helps to explain the exaggerated male spectrum termed as the extreme male behavior.[35]

See also

Citations

- Frith, Uta (20 December 2001). "Mind Blindness and the Brain in Autism". Neuron. 32 (6): 969–979. doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00552-9. PMID 11754830.

- Gallagher, Helen L.; Frith, Christopher D. (1 February 2003). "Functional imaging of 'theory of mind'" (PDF). Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 7 (2): 77–83. doi:10.1016/S1364-6613(02)00025-6. PMID 12584026.

- Pijnenborg; et al. (June 2013). "Insight in schizophrenia: associations with empathy". European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 263 (4): 299–307. doi:10.1007/s00406-012-0373-0. PMID 23076736.

- Baron-Cohen, Simon (25 March 2009). "Autism: The Empathizing-Systemizing (E-S) Theory". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1156, The Year in Cognitive Neuroscience (1): 68–80. Bibcode:2009NYASA1156...68B. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04467.x. PMID 19338503.

- Jurecic, Ann (Spring 2006). "Mindblindness: Autism, Writing, and the Problem of Empathy". Literature and Medicine. 25 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1353/lm.2006.0021. PMID 17040082.

- Brune, M. (1 January 2005). ""Theory of Mind" in Schizophrenia: A Review of the Literature". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 31 (1): 21–42. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbi002. PMID 15888423.

- Baron-Cohen, Simon (1990). "Autism: a specific cognitive disorder of 'mind-blindness". International Review of Psychiatry. 2 (1): 81–90. doi:10.3109/09540269009028274.

- Baron-Cohen, Simon (January 1990). "Autism: A Specific Cognitive Disorder of & lsquo;Mind-Blindness'". International Review of Psychiatry. 2 (1): 81–90. doi:10.3109/09540269009028274. ISSN 0954-0261.

- Lombardo, Michael V.; Baron-Cohen, Simon (1 March 2011). "The role of the self in mindblindness in autism". Consciousness and Cognition. 20 (1): 130–140. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2010.09.006. PMID 20932779.

- Wellman, Henry M.; Cross, David (May 2001). "Theory of Mind and Conceptual Change". Child Development. 72 (3): 702–707. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00309. ISSN 0009-3920. PMID 11405576.

- Okamoto, Yukari (2010), "Children's Developing Understanding of Number: Mind, Brain, and Culture", The Developmental Relations among Mind, Brain and Education, Springer Netherlands, pp. 129–148, doi:10.1007/978-90-481-3666-7_6, ISBN 978-90-481-3665-0

- Al-Hilawani, Yasser A.; Easterbrooks, Susan R.; Marchant, Gregory J. (2002). "Metacognitive Ability From a Theory-of-Mind Perspective: A Cross-Cultural Study of Students With and Without Hearing Loss". American Annals of the Deaf. 147 (4): 38–47. doi:10.1353/aad.2012.0230. ISSN 1543-0375. PMID 12592804.

- Stone, V.E.; Baron-Cohen, S.; Knight, R.T. (September 1998). "Frontal lobe contributions to the theory of mind". Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 10 (5): 640–656. doi:10.1162/089892998562942. PMID 9802997.

- Gallagher, Helen L.; Frith, Christopher D. (February 2003). "Functional imaging of 'theory of mind'". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 7 (2): 77–83. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.319.778. doi:10.1016/s1364-6613(02)00025-6. ISSN 1364-6613. PMID 12584026.

- Josef Perner & Birgit Lang (1 September 1999). "Development of theory of mind and executive control". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 3 (9): 337–344. doi:10.1016/s1364-6613(99)01362-5. PMID 10461196.

- Carruthers, Peter (1996). "Chapter 16. Autism as Mind-Blindness: an elaboration and partial defence (pp. 257 ff.)". In Carruthers, Peter; Smith, Peter K. (eds.). Theories of Theories of Mind. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-55916-4.

- Havet-Thomassin; P. Allain; F. Etcharry-Bouyx; D. le Gall (2006). "What about theory of mind after severe brain injury?". Brain Injury. 20 (1): 83–91. doi:10.1080/02699050500340655. PMID 16403703.

- Bird, C. M. (14 January 2004). "The impact of extensive medial frontal lobe damage on 'Theory of Mind' and cognition". Brain. 127 (4): 914–928. doi:10.1093/brain/awh108. PMID 14998913.

- Frith, Uta; Frith, C.D (October 2001). "The biological basis of social interaction". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 10 (5): 151–155. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.00137.

- Frith, Uta (December 2001). "Mind Blindness and the Brain in Autism". Neuron. 32 (6): 969–979. doi:10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00552-9. ISSN 0896-6273. PMID 11754830.

- Carruthers, Peter; Smith, Peter K., eds. (1996-02-23). Theories of Theories of Mind. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511597985. ISBN 9780521551106.

- Baron-Cohen, S. (1 July 2004). "The cognitive neuroscience of autism". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 75 (7): 945–948. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2003.018713. PMC 1739089. PMID 15201345.

- Bowler, Dermont. M. (July 1992). "Theory of Mind in Asperger's syndrome". Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 33 (5): 877–893. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.1992.tb01962.x. PMID 1378848.

- Ozonoff, S; Rogers, S. & Pennington, B. (November 1991). "Asperger's syndrome: Evidence for an empirical distinction from high-functioning autism". Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 32 (7): 1107–1122. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.1991.tb00352.x. PMID 1787139.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Solerdelcoll Arimany, Mireia (2017-08-23). "Diagnostic stability of autism spectrum disorders with the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria". doi:10.26226/morressier.5971be87d462b80290b53368. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Definitions, Qeios, 2020-02-07, doi:10.32388/gskru1 Missing or empty

|title=(help);|chapter=ignored (help) - Johnson, C. P.; Myers, S. M. (2007-10-29). "Identification and Evaluation of Children With Autism Spectrum Disorders". Pediatrics. 120 (5): 1183–1215. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-2361. ISSN 0031-4005. PMID 17967920.

- Brune, M. (2005-01-01). ""Theory of Mind" in Schizophrenia: A Review of the Literature". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 31 (1): 21–42. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbi002. ISSN 0586-7614. PMID 15888423.

- Langdon, Robyn (2007) [2005]. "Chapter 21. Theory of Mind in Schizophrenia (pp. 323 ff.)". In Malle, Bertram F.; Hodges, Sara D. (eds.). Other Minds. How Humans Bridge the Divide Between Self And Others. New York City: Guilford Press. ISBN 978-1-593-85468-3.

- Cleghorn, John M.; Albert, Martin L. (1990), "Modular Disjunction in Schizophrenia: A Framework for a Pathological Psychophysiology", International Perspectives Series: Psychiatry, Psychology, and Neuroscience, Springer New York, pp. 59–80, doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-3248-3_3, ISBN 978-0-387-97221-3

- Harrington, Leigh; Siegert, Richard; McClure, John (August 2005). "Theory of mind in schizophrenia: A critical review". Cognitive Neuropsychiatry. 10 (4): 249–286. doi:10.1080/13546800444000056. ISSN 1354-6805. PMID 16571462.

- Klin, Ami., Folkmar, Fred R., Sparrow, Sara S. (July 1992). "Autistic Social Dysfunction: Some limitations of the Theory of Mind hypothesis". Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 33 (5): 861–876. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.1992.tb01961.x. PMID 1378847.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Shanker, S. (1 October 2004). "The Roots of Mindblindness". Theory & Psychology. 14 (5): 685–703. doi:10.1177/0959354304046179.

- Smukler, David (February 2005). "Unauthorized Minds: How 'Theory of Mind' Theory Misrepresents Autism". Mental Retardation. 43 (1): 11–24. doi:10.1352/0047-6765(2005)43<11:UMHTOM>2.0.CO;2. PMID 15628930.

- Baron-Cohen, S.; Knickmeyer, Rebecca S.; Belmonte, Mathew S. (4 November 2005). "Sex Differences in the Brain: Implications for Explaining Autism" (PDF). Science. 310 (5749): 819–823. Bibcode:2005Sci...310..819B. doi:10.1126/science.1115455. PMID 16272115.

References

- Geoffrey Cowley, "Understanding Autism," Newsweek, July 31, 2000.

- Simon Baron-Cohen, "First lessons in mind reading," The Times Higher Education Supplement, July 16, 1995.

- Suddendorf, T., & Whiten, A. (2001). "Mental evolution and development: evidence for secondary representation in children, great apes and other animals." Psychological Bulletin, 629–650.

- Al-Hilawani, Y. A., Easterbrooks, S. R., & Marchant, G. J. (2002). Metacognitive ability from a theory-of-mind perspective: A cross-cultural study of students with and without hearing loss. American Annals of the Deaf, 38-47.

- Baron-Cohen, S. (1990). Autism: A Specific Cognitive Disorder of & lsquo; Mind-Blindness’. International Review of Psychiatry, 2(1), 81-90. Brüne, M. (2005). “Theory of mind” in schizophrenia: a review of the literature. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 31(1), 21-42.

- Carruthers, P., & Smith, P. K. (Eds.). (1996). Theories of theories of mind. Cambridge University Press.

- Cleghorn, J. M., & Albert, M. L. (1990). Modular disjunction in schizophrenia: A framework for a pathological psychophysiology. In Recent Advances in Schizophrenia (pp. 59–80). Springer, New York, NY.

- Frith, U. (2001). Mind blindness and the brain in autism. Neuron, 32(6), 969-979.

- Gallagher, H. L., & Frith, C. D. (2003). Functional imaging of ‘theory of mind’. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 7(2), 77-83.

- Harrington, L., Siegert, R., & McClure, J. (2005). Theory of mind in schizophrenia: a critical review. Cognitive Neuropsychiatry, 10(4), 249-286.

- Hyman, S. L. (2013). New DSM-5 includes changes to autism criteria. AAP News, 4, 20130604-1.

- Johnson, C. P., & Myers, S. M. (2007). Identification and evaluation of children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics, 120(5), 1183-1215.

- National Autism Center. (2020). Online post. https://www.nationalautismcenter.org/

- Wang, Z. (2010). Mindful learning: Children’s developing theory of mind and their understanding of the concept of learning.

- Wellman, H. M. (1992). The MIT Press series in learning, development, and conceptual change. The child's Theory of Mind. The MIT Press.