Milcah Martha Moore

Milcah Martha Moore (1740–1829) was an 18th-century American Quaker poet, the creator of a manuscript commonplace book featuring the work of women writers of her circle and compiler of a printed book of prose and poetry.

.jpg)

Early years

Milcah Martha Hill was born in 1740 to Richard and Deborah (Moore) Hill in Funchal on the island of Madeira. She was one of eight children (six of them girls, of whom she was the youngest); one of her sisters would later become known under her married name of Margaret Morris for a fragmentary journal she kept during the revolutionary period of 1776-78 for Milcah's amusement.[1] Her father was a physician and trader who had moved to Madeira as a result of financial setbacks, and her mother was a granddaughter of William Penn's friend Thomas Lloyd. During her childhood, her father's fortunes improved, and in 1761 the family moved to the Delaware Valley of Pennsylvania. Milcah's mother died shortly before the journey was made, and her father not long after.

Career

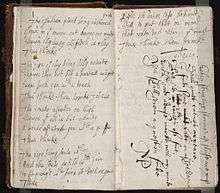

Women of the period used commonplace books as a method of creating a private, informal historical record of their own era, collecting in them aphorisms, quotations, advice, poems, letters, reminiscences, recipes, and other materials of personal significance.[2] Many of these women either found difficulty getting their work published or did not want to make their work public, so they circulated their writings in manuscript, forming what has been termed a "third sphere" of discourse, neither fully public nor fully private.[3] Moore's own commonplace book, which she called "Martha Moore's Book", focused on poetry written by women in her circle and included over 125 poems (some of them quite long) by more than a dozen writers. The exact number of contributors is uncertain because some of the women are represented under pseudonyms or initials, not all of which have been securely connected to known individuals. About half of the poems are by Moore's second cousin Hannah Griffitts, while many of the rest are by Susanna Wright and Elizabeth Graeme Fergusson, who are considered three of the era's most talented women writers of the eastern seaboard.[4] Of particular value are those by the polymath Wright, only four of whose poems were known before the discovery of Moore's book.[5]

The collection was made around the time of the American Revolution, between the mid 1760s and 1778, and a number of the poems, especially those by Griffitts, are satires on political events of the day. Occasional verse is a favored form—especially elegies and birthday poems—and there are also hymns and verse letters. Apart from poems, there are extracts from a journal kept by Fergusson during a trip to England as well as some passages copied from the works of Benjamin Franklin, Patrick Henry, and Samuel Fothergill.[6] With their strongly moral tone and striving towards personal improvement, it has been suggested that compendia such as Moore's were precursors to the advice columns that would become a staple of 19th century newspapers, and which had just begun to appear in the early republic.[7]

Moore's commonplace book was first published in 1997 under the title Milcah Martha Moore's Book.[8] Scholars Catherine La Courreye Blecki and Karin A. Wulf, who edited the book for publication, consider it "the richest surviving body of evidence revealing the nature and substance of women's intellectual community in British America."[9] In general, scholars of the period similarly value it for its contribution to understanding of the role of Quaker women in late 18th century American political and cultural life.[10][2][11]

Moore herself was a poet as well as an appreciator of other writers' verse. Her own poems, together with verse by other writers, aphorisms, and proverbs—some of it culled from her commonplace book—were published in a textbook that she edited for young readers in 1787 entitled Miscellanies, Moral and Instructive, in Prose and Verse; Collected from Various Authors, for the Use of Schools, and Improvement of Young Persons of Both Sexes.[12] The phrase "moral and instructive" gives a clear idea of the nature of her own poetry.[6] Endorsed by Benjamin Franklin in a brief statement in the book's front matter, Moore's book was used in Philadelphia-area schools until well into the 19th century.[13] Earnings from the book's sales went towards a school for indigent girls that Moore founded in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, and Moore herself taught there for the rest of her life.[10][14] Upon her death in 1829, she left the school an endowment.[14]

Personal life

In 1767 Milcah married the physician Charles Moore, who was a cousin of hers. Since the Quakers did not favor marriages between close kin, the couple was expelled from the Society of Friends. They lived at various times in Philadelphia, an important literary and political center of life in the American Revolutionary period, and in New Jersey.[10]

After her husband died in 1801, Moore rejoined the Quakers.[6] She died in New Jersey in 1829.

References

- Morris, Margaret. "The Revolutionary Journal of Margaret Morris, of Burlington, N.J., December 6, 1776, to June 11, 1778". Bulletin of Friends' Historical Society of Philadelphia, vol. 9, no. 1, May 1919, pp. 2-14.

- Stabile, Susan M. Memory's Daughters: The Material Culture of Remembrance in Eighteenth-Century America. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2004.

- Baker, Noelle A. "'Let Me Do Nothing Smale': Mary Moody Emerson and Women's 'Talking' Manuscripts". Journal of the American Renaissance, (2011): 57:1-2.

- Kelley, Mary. "'A More Glorious Revolution': Women's Antebellum Reading Circles and the Pursuit of Public Influence." New England Quarterly (2003): 163-196.

- Blecki, Catherine L., and Lorett Treese. "Susanna Wright's" The Grove": A Philosophic Exchange with James Logan." Early American Literature 38.2 (2003): 239-255.

- MacLean, Maggie. "Milcah Martha Moore: Quaker Writer and Poet". History of American Women website, Oct. 27, 2008.

- Logan, Lisa M. "" Dear Matron—": Constructions of Women in Eighteenth-Century American Periodical Advice Columns." Studies in American Humor (2004): 57-62.

- Blecki, Catherine La Courreye, and A. Wulf, eds. Milcah Martha Moore's Book: A Commonplace Book from Revolutionary America. Pennsylvania State University Press, 1997.

- "Milcah Martha Moore's Book". Penn State University Press website.

- Klepp, Susan E. "Milcah Martha Moore's Book: A Commonplace Brook from Revolutionary America by Catherine La Courreye Blecki, Karin A. Wulf". Pennsylvania History 65:4 (Autumn 1998). (Review).

- Mekeel, Arthur J. "Milcah Martha Moore's Book: A Commonplace Book from Revolutionary America (review)". Quaker History 88:1 (Spring 1999).

- Moore, Milcah Martha, ed. Miscellanies, Moral and Instructive, in Prose and Verse; Collected from Various Authors, for the Use of Schools, and Improvement of Young Persons of Both Sexes. Philadelphia: Joseph James, 1787.

- Barone, Dennis. "Before the Revolution: Formal Rhetoric in Philadelphia During the Federal Era." Pennsylvania History (1987): 244-262.

- "Revolutionary Visions: Women's Initiative(s)". Educating the Youth of Pennsylvania: Worlds of Learning in the Age of Franklin, University of Pennsylvania Libraries website.