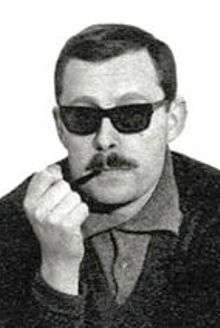

Michel Mortier

Michel Mortier (1925 – 22 May 2015) was a French furniture designer, interior designer and architect who was known for his modern designs.

Michel Mortier | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1925 Paris, France |

| Died | 22 May 2015 |

| Nationality | French |

| Occupation | Designer |

Life

Michel Mortier was born in Paris in 1925. He was admitted to the École des arts appliqués à l’industrie (School of Industrial Art), where he studied under René Gabriel and Louis Sognot.[1] He joined the Studium-Louvre in 1944, the workshop for modern decorative art run by Etienne-Henri Martin for the Grands Magasins du Louvre department store. The workshop produced designs for the growing number of customers who wanted modern styles of decoration.[2] Mortier's association with Martin led to work with the furniture department of the Bon Marché in Brussels.[3] Mortier was discovered by Marcel Gascoin, a central figure in French post-war design who surrounded himself with young talent to produce furniture sets.[2] In 1949 Gascoin founded ARHEC, Aménagement rationnel de l'habitation et des collectivités (Rational Improvement of Housing and Communities), to produce and distribute furniture sets.[4] From 1949 to 1954 Michel Mortier was the first director of Arhec.[2]

Mortier won the Gold Medal at the Milan Triennale in 1954.[2] That year he formed an association called the Atelier de Recherche Plastique (ARP: Plastic Research Workshop) with Pierre Guariche and Joseph-André Motte, whom he had met in Gascoin's studio.[5] The ARP had an exhibit at the Salon des arts ménagers in 1954, where Mortier showed a modular storage unit with an ingenious assembly system that was the origin for a range of products by Minvielle, a leading brand in the 1950s and 1960s.[6] For about three years the ARP designed a wide range of furniture for the living room, parent's bedroom and child's bedroom for the manufacturer Charles Minvielle.[5] The ARP partnership broke up in 1957.[2]

Mortier became artistic director of the store La Maison Française 55, and designed many products for leading manufacturers including chairs for Steiner and lights for Disderot and Verre Lumière. In 1959 Mortier founded his own interior design agency, the Habitation esthétique industrielle mobilier. He moved to Canada where he was introduced to graphisme in Montreal and taught at JM Blier Furniture & Design.[7] He also worked as a freelance journalist in his spare time.[8] In 1963 he won the Prix René Gabriel, awarded annually to the designer of a furniture series that combined quality and economy. He participated in the Expo 67 in Montreal, Quebec, Canada.[7]

Self-taught, Mortier designed several elegant private homes in the 1970s, and in 1977 obtained a diploma as an architect from the Île-de-France regional architecture council.[7] He taught interior design at the École nationale supérieure des arts décoratifs in Paris, the École des arts appliqués and the École supérieure d’arts graphiques Penninghen.[2] He became a painter towards the end of his life.[6] Michel Mortier died on 22 May 2015 at the age of 90.[2] He was survived by his children Christine Taïeb, Richard Mortier and Charlotte Mortier.[1]

Work

Mortier was among the young post-war designers who rejected Art Deco and the popular neo-Louis XVI and Louis XIII styles.[2] The work of the three young designers in ARP was unusual for the time, leading to truly modern concepts.[6] Mortier developed a child's room in the 1970s that was considered very avant-garde at the time, with flat colored surfaces that define the different uses of the built-in units: storage, work and play. His creations, with elegant lines influenced by Danish design, drew wide praise from the press.[6] His best known product is the Lampe 10576 produced by Verre Lumière.[7] His work is held in major public collections including the Centre national des arts plastiques, the Musée d'art moderne et contemporain de Saint-Etienne Métropole and the Collection nationale des arts décoratifs.[1]

Publications

- Gerd Hatje; Elke Kaspar; Julius Arthur Marcus; Michel Mortier (1971-01-01). Neue Möbel. Praeger. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-85458-480-2.

- Michel Mortier (1972). Décor et couleurs. J. Tallandier. p. 58.

Notes

Sources

- "Décès de Michel Mortier". Archicréé. Retrieved 2015-08-14.

- "Gascoin, Marcel (1907-1986)". BnF. Retrieved 2015-06-04.

- La galerie Pascal (2015-06-03). "Décès du designer français Michel Mortier" (in French). Retrieved 2015-08-14.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lorelle, Véronique (2015-06-04). "Michel Mortier, designer de la modernité, est mort". Le Monde (in French). Retrieved 2015-08-14.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Michel MORTIER" (in French). Galerie Alexandre Guillemain. Retrieved 2015-08-14.

- Prodhon, Françoise-Claire (May–June 2006). "PIERRE GUARICHE". Intramuros (124). Archived from the original on 2015-05-21. Retrieved 2015-05-19.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tournemire, Lara (2015-06-04). "Le designer Michel Mortier est décédé". Connaissance des Arts (in French). Retrieved 2015-08-14.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Zamboni, Agnès (2015). "Hommage à un grand designer français: Michel Mortier". Maison.com (in French). Retrieved 2015-08-14.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)