Metorchis conjunctus

Metorchis conjunctus, common name Canadian liver fluke, is a species of trematode parasite in the family Opisthorchiidae. It can infect mammals that eat raw fish in North America. The first intermediate host is a freshwater snail and the second is a freshwater fish.

| Metorchis conjunctus | |

|---|---|

| |

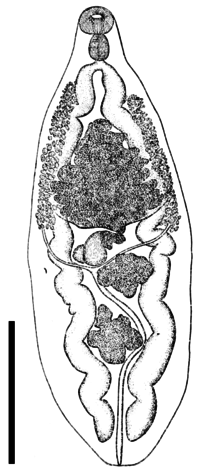

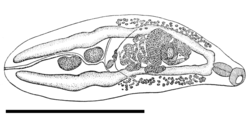

| Drawing of ventral view of Metorchis conjunctus, scale bar is 1 mm | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Subclass: | |

| Order: | |

| Suborder: | |

| Superfamily: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | M. conjunctus |

| Binomial name | |

| Metorchis conjunctus Cobbold, 1860 | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

|

Parametorchis noveboracensis (Hung, 1926)[2] | |

Taxonomy

This species was discovered and described by Thomas Spencer Cobbold in 1860.

Distribution

The distribution of M. conjunctus includes:

Description

The body of M. conjunctus is pear-shaped and flat.[6] The body length is 1⁄4–3⁄8 inch (6.4–9.5 mm).[6] It has a weakly muscular terminal oral sucker.[3] No prepharynx is present.[3] The pharynx is strongly muscular.[3] The esophagus is very short.[3] The intestinal ceca vary from almost straight to sinuous.[3] The acetabulum is slightly oval and weakly muscular.[3] The male has an anterior testis and a posterior testis.[3] The testes vary from almost round to oval, and may be deeply lobed or slightly indented.[3] No cirrus pouch is found.[3] The seminal vesicle is slender.[3] The ovary is trilobed.[3] The receptaculum seminis is elongated or pyriform, and slightly twisted, and situated to the right and behind the ovary.[3]

The eggs are oval and yellowish brown.[3]

Lifecycle

The first intermediate host of M. conjunctus is a freshwater snail, Amnicola limosus.[4]

The second intermediate host is a freshwater fish: Catostomus catostomus,[4] Salvelinus fontinalis,[4] Perca flavescens,[4] or Catostomus commersoni.[7] Metacercaria of M. conjunctus were also found in northern pike (Esox lucius).[8]

The definitive hosts are fish-eating mammals such as domestic dogs (Canis lupus familiaris), domestic cats (Felis catus), wolves (Canis lupus),[5] red foxes (Vulpes vulpes),[9] gray foxes (Urocyon cinereoargenteus),[1] coyotes (Canis latrans), raccoons (Procyon lotor),[5] muskrats (Ondatra zibethicus), American minks (Neovison vision),[5] fishers (Martes pennanti),[4][10] or bears.[8] It can also infect humans.[7] It lives in the bile duct and in the gallbladder.[6]

Effects on human health

M. conjunctus causes a disease called metorchiasis.[11] It has been known to infect humans since 1946.[4] Humans had eggs of M. conjunctus in their stools, but they were asymptomatic.[8] Sashimi from raw Catostomus commersoni was identified as a source for an outbreak in Montreal in 1993.[7] It was the first symptomatic disease in humans caused by M. conjunctus.[8]

Symptoms

After ingestion of fish infected with M. conjunctus, about 1–15 days are needed for symptoms to occur, namely for eggs to be detected in the stool (incubation period).[12]

The acute phase consists of upper abdominal pain and low-grade fever.[7] High concentrations of eosinophil granulocytes are in blood.[7] Also, higher concentrations of liver enzymes are seen.[7] When untreated, symptoms may last from 3 days to 4 weeks.[7] Symptoms of chronic infection were not reported.[12]

Diagnosis and treatment

Eggs of M. conjunctus can be found by stool analysis.[8] Serologic analysis can be also used - ELISA test for IgG antibodies against antigens of M. conjunctus.[8]

Drugs used to treat infestation include praziquantel:[7] 75 mg/kg in three doses per day (the same dosage applies for adults and for children).[8][13]

Effects on animal health

Watson and Croll (1981)[14] studied symptoms of cats. Prevention includes feeding with cooked fish (not raw fish).[6]

M. conjunctus was found to be a common infection of domestic dogs in Indian settlements in 1973.[15]

The prevalence of M. conjunctus in wolves in Canada is 1–3%.[12] In wolves, M. conjunctus causes cholangiohepatitis with periductular fibrosis in the liver.[5] It sometimes causes chronic inflammation and fibrosis of the pancreas in wolves.[5]

References

This article incorporates public domain text from the reference[3]

- Mills J. H. & Hirth R. S. (1968). "Lesions Caused by the Hepatic Trematode, Metorchis conjunctus, Cobbold, 1860: A Comparative Study in Carnivora". Journal of Small Animal Practice 9(1): 1–6. doi:10.1111/j.1748-5827.1968.tb04678.x.

- Hung See-Lü (1926). "A new species of fluke, Parametorchis noveboracensis, from the cat in the United States". Proceedings of the United States National Museum 69(2627): 1–2.

- Price E. W. (1929). "Two new species of trematodes of the genus Parametorchis from fur-bearing animals". Proceedings of the United States National Museum 76(2809): 1–5.

- Chai J. Y., Darwin Murrell K. & Lymbery A. J. (2005). "Fish-borne parasitic zoonoses: Status and issues". International Journal for Parasitology 35(11–12): 1233–1254. doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2005.07.013.

- Wobeser G., Runge W. & Stewart R. R. (1983). "Metorchis conjunctus (Cobbold, 1860) infection in wolves (Canis lupus), with pancreatic involvement in two animals". Journal of Wildlife Diseases 19(4): 353–356. PMID 6644936.

- Axelson R. D. (1962). "Metorchis Conjunctus Liver Fluke Infestation in a Cat". Canadian Veterinary Journal 3(11): 359–360. PMID 17421548. PDF.

- MacLean J. D., Arthur J. R., Ward B. J., Gyorkos T. W., Curtis M. A. & Kokoskin E. (1996). "Common-source outbreak of acute infection due to the North American liver fluke Metorchis conjunctus". The Lancet 347(8995): 154–158. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(96)90342-6

- Behr M. A., Gyorkos T. W., Kokoskin E., Ward B. J., MacLean J. D. (1998). "North American liver fluke (Metorchis conjunctus) in a Canadian aboriginal population: a submerging human pathogen?" Canadian Journal of Public Health 89: 258–259. PMID 9735521. PDF.

- Smith H. J. (1978). "Parasites of red foxes in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia". Journal of Wildlife Diseases 14(3): 366–370. PMID 691132.

- Dick T. A & Leonard R. D. (1979). "Helminth parasites of fisher Martes pennanti (Erxleben) from Manitoba, Canada". Journal of Wildlife Diseases 15(3): 409–412. PMID 574167.

- Dennis J. Richardson; Peter J. Krause (6 December 2012). North American Parasitic Zoonoses. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 86. ISBN 978-1-4615-1123-6.

- Waikagul J. & Thaekham U. (2014). Approaches to Research on the Systematics of Fish-Borne Trematodes. Academic Press, 130 pp., page 6–7.

- "FLUKE, hermaphroditic, infection"., 2 pp., accessed 31 December 2015.

- Watson T. G & Croll N. A. (1981). "Clinical changes caused by the liver fluke Metorchis conjunctus in cats". Veterinary Pathology 18(6): 778–785. doi:10.1177/030098588101800608.

- Unruh D. H., King J. E., Eaton R. D. & Allen J. R. (1973). "Parasites of dogs from Indian settlements in northwestern Canada: a survey with public health implications". Canadian Journal of Comparative Medicine 37(1): 25–32. PMID 4265550.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Metorchis conjunctus. |

- Cameron T. W. M. (1944). "The morphology, taxonomy and life history of Metorchis conjunctus". Canadian Journal of Research 22: 6–16. doi:10.1139/cjr44d-002.

- Eaton R. D. P. (1975). "Metorchiasis – A Canadian Zoonosis". Epidemiological Bulletin (National Health and Welfare, Canada) 19: 62–68.