Menna

The ancient Egyptian official named Menna carried a number of titles associated with the agricultural estates of the temple of Karnak and the king. Information about Menna comes primarily from his richly decorated tomb (TT 69) in the necropolis of Sheikh Abd al-Qurna at Thebes. Though his tomb has traditionally been dated to the reign of Thutmose IV, stylistic analysis of the decoration places the majority of construction and decoration of the tomb to the reign of Amenhotep III.[1]

| Menna in hieroglyphs |

|---|

Titles

Menna was unique for the 18th Dynasty because he carried titles associated with both temple and palace administration. Though the pharaoh technically owned both temple and palace agricultural estates, administration of these institutions was traditionally separated.[2] Egyptologist Dr. Melinda Hartwig argues that the high cost of Amenhotep III’s ambitious building projects resulted in a consolidation of temple and royal grain administration in order to pay the workers Amenhotep III utilized to construct his monuments.[3] These workers were typically paid with grain, so the combination of temple and palace administration under one person allowed for greater efficiency of wealth redistribution.[4]

Menna’s titles as recorded in his tomb chapel are:

- Scribe

- Overseer of Fields of Amun

- Overseer of Plowlands of Amun

- Overseer of Fields of the Lord of the Two Lands

- Scribe of the Fields of the Lord of the Two Lands of South and North

- Scribe of the Lord of the Two Lands[3]

Family

Menna’s wife, Henuttawy, was likely a woman from a more influential family. She herself carried the titles of "Chantress of Amun" and "Lady of the House", both of which speak to her noble birth and possession of property.[5] Her father may well have been Amenhotep-sa-se (TT75) who held the title of "second prophet of Amun" placing him second only to the high priest within the hierarchy of Karnak temple.[6]

Menna and Henuttawy had five children: two sons, Se and Kha, and three daughters, Amenemweskhet, Nehemet, and Kasy. Amenemweskhet held the title of "Lady-in-Waiting", which tied her closely to the royal household. Her sister, Nehemet is depicted wearing a crown typically worn by ladies-in-waiting and may have also carried this title. In Menna's tomb (TT69) Nehemet is labelled with the words "mAat-Xrw" which means "true of voice" or "justified". This indicates that she was likely deceased by the time the tomb was decorated. Menna's son, Se, was a "scribe of counting grain of Amun", and Kha was a minor priest known as a "wab-priest".[7]

Two more women, Way and Nefery are depicted in Menna's tomb. They both carry the titles of "Chantress of Amun" and "Lady of the House". They are also labelled with the word "sA.t" which can mean 'daughter' but can also mean 'daughter-in-law'. Their title of "Lady of the House" indicates that they were married, so they may well have been the wives of Se and Kha.[7]

Tomb (TT69)

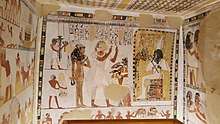

Much of the information that remains about Menna comes from his tomb in the Theban Necropolis, TT69. Like many Egyptian tombs of the time, the tomb consists of a sunken forecourt, a broad outer room (known as the 'transverse room' or 'broad hall') a long inner room (the 'long hall"), a central shrine, and a sloping passage leading to a burial chamber.[8] The broad hall, long hall, and shrine of Menna’s tomb were beautifully decorated, and still retain much of their vibrant color. The decoration of the tomb focused on Menna's position within the Egyptian administration, and on his transition from a living person in this world, to an effective and powerful ancestor in the next. Scenes of agriculture are common, as are scenes showing offering bringers giving food and drink to Menna, often accompanied by his wife, Henuttawy. Scenes of the funeral rites and judgement before Osiris also appear.

Art historical analysis of the style of decoration within the tomb has shown that though the tomb may have been begun during the reign of Thutmose IV, the majority of the painting was carried out during the reign of Amenhotep III.[9][10][11] TT69 is notable for having the earliest depiction of the Weighing of the Heart ceremony to appear on the wall of a tomb.[12]

See also

References

- Hartwig, Melinda (2013). The Tomb Chapel of Menna (TT69): The Art, Culture, and Science of Painting in an Egyptian Tomb. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press. p. 19.

- Säve-Söderbergh, Torgny (1957). Four Eighteenth Dynasty Tombs. Oxford: Griffith Institute at the University Press. p. 36.

- Hartwig, Melinda (2013). The Tomb Chapel of Menna (TT69): The Art, Culture, and Science of Painting in an Egyptian Tomb. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press. p. 16.

- Hartwig, Melinda (2013). The Tomb Chapel of Menna (TT69): The Art, Culture, and Science of Painting in an Egyptian Tomb. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press. pp. 17–18.

- Johnson, Janet (1996). "The Legal Status of Women in Ancient Egypt" in Mistress of the House, Mistress of Heaven. New York: Hudson Hills Press. pp. 175–186.

- Whale, Sheila (1989). The Family in the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt. Sydney: The Australian Centre for Egyptology. p. 208.

- Hartwig, Melinda (2013). The Tomb Chapel of Menna (TT69): The Art, Culture, and Science of Painting in an Egyptian Tomb. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press. p. 18.

- Hartwig, Melinda (2013). The Tomb Chapel of Menna (TT69): The Art, Culture, and Science of Painting in an Egyptian Tomb. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press. p. 9.

- Kampp, Friederike (1996). Die Thebanische Nekropole: Zum Wandel des Grabgedankens von der XVIII. bis zur XX. Dynastie. Band 1. Mainz: Philip van Zabern. p. 294.

- Kozloff, Arielle (1990). "Theban Tomb Paintings from the Reign of Amenhotep III: Problems in Iconography and Chronology" in The Art of Amenhotep III: Art Historical Analysis. Cleveland: Indiana University Press. pp. 268–273.

- Hodel-Hoenes, Sigrid (2000). Life and Death in Ancient Egypt: Scenes from Private Tombs in New Kingdom Thebes. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press. pp. 302.

- Hartwig, Melinda (2013). The Tomb Chapel of Menna (TT69): The Art, Culture, and Science of Painting in an Egyptian Tomb. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press. p. 74.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Menna. |