Melitaea (Thessaly)

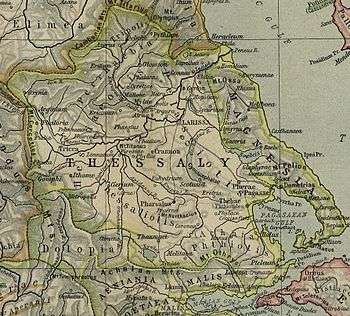

Melitaea or Meliteia (Ancient Greek: Μελιταία[1][2][3] or Μελίτεια[4] or Μελιτία[5]) was a town and polis (city-state)[6] of Phthiotis in ancient Thessaly, situated near the river Enipeus, at the distance of 10 stadia from the town of Hellas, whence the residents of Melitaea had come.[1] The inhabitants of Melitaea affirmed that their town was anciently called Pyrrha, and they showed in the agora the tomb of Hellen, the son of Deucalion and Pyrrha.[1] According to Greek mythology its eponymous founder had been Melitaea and there was a legend according to which Aspalis, a beautiful maiden of the place, had been hanged to avoid being possessed by a tyrant of the city which they called Tartarus. Astygites, the brother of Aspalis, killed the tyrant after disguising himself as his sister. It was believed that the body of Aspalis was not found because it was taken by the gods and in its place a statue appeared next to another statue of Artemis that was already in the city. In this new statue, called Aspalis Amilete Hekaërge, the maidens of the city hung a virgin goat every year, just as Aspalis had been hanged as a virgin.[7]

Thucydides relates that during the Peloponnesian War, when Brasidas was marching through Thessaly to Macedonia, his Thessalian friends met him at Melitaea in order to escort him (424 BCE),[5] learning from this narrative that the town was one day's march from Pharsalus, whither Brasidas proceeded on leaving the former place. In the Lamiac War the allies left their baggage at Melitaea, when they proceeded to attack Leonnatus.[8] Subsequently Melitaea was in the hands of the Aetolians. Philip V of Macedon attempted to take it (217 BCE), but he did not succeed, in consequence of his scaling-ladders being too short.[4] Melitaea is also mentioned in the Periplus of Pseudo-Scylax,[9] and by Stephanus of Byzantium,[3] Pliny the Elder,[2], and Ptolemy who erroneously calls it Μελίταρα (Melitara).[10]

Melitaea's site is near the town of Melitaia (Μελιταία), formerly Avaritsa but renamed to reflect its association with the ancient city, in the municipality of Domokos.[11][12]

References

- Strabo. Geographica. 9.5.10. Page numbers refer to those of Isaac Casaubon's edition.

- Pliny. Naturalis Historia. 4.9.16.

- Stephanus of Byzantium. Ethnica. s.v.

- Polybius. The Histories. 5.97, 9.18.

- Thucydides. History of the Peloponnesian War. 4.78.

- Mogens Herman Hansen & Thomas Heine Nielsen (2004). "Thessaly and Adjacent Regions". An inventory of archaic and classical poleis. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 715. ISBN 0-19-814099-1.

- Antoninus Liberalis, Metamorphoses, 13.

- Diodorus Siculus. Bibliotheca historica (Historical Library). 18.15.

- Periplus of Pseudo-Scylax, p. 24

- Ptolemy. The Geography. 3.13.46.

- Richard Talbert, ed. (2000). Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World. Princeton University Press. p. 55, and directory notes accompanying.

- Lund University. Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire.

![]()