Kuttab

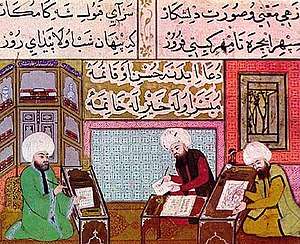

A kuttab (Arabic: كُتَّاب kuttāb, plural: kataatiib, كَتاتِيبُ[1]) is an Arabic word meaning elementary school. Though the kuttab was primarily used for teaching children in reading, writing, grammar, and Islamic studies, such as Qira'at (Quranic recitation), other practical and theoretical subjects were also often taught.[2] Until the 20th century, kuttabs were the prevalent means of mass education in much of the Islamic world.

Kuttab refers to only elementary schools in Arabic. Maktab is used in Dari Persian in Afghanistan as an equivalent term to school, including both primary and secondary schools. Avicenna used the word maktab in the same sense.

The kuttāb represents an old-fashioned method of education in Egypt and Muslim majority countries, in which a sheikh teaches a group of students who sit in front of him on the ground. The curriculum includes Islam and Quranic Arabic, but focused mainly on memorising the Quran. With the development of modern schools, the number of kuttabs has declined. Kuttāb means "writers", plural katatīb / katātīb.

In common Modern Arabic usage, maktab means "office" while maktabah means "library" or "(place of) study" and kuttāb is a plural word meaning "authors".[3][4]

Name

This institution can also be called a maktab (مَكْتَب) or maktaba (مَكْتَبَة) in Arabic—with many transliterations. In Morocco, it is referred to as a m'siid (مْسِيد). In Persian, it is a or Maktabkhaneh مکتبخانه.

History

In the medieval Islamic world, an elementary school was known as a maktab, which dates back to at least the 10th century. Like madrasahs (which referred to higher education), a maktab was often attached to a mosque.[2] In the 16th century, the Sunni Islamic jurist Ibn Hajar al-Haytami discussed Maktab schools.[5] In response to a petition from a retired Shia Islamic judge who ran a Madhab elementary school for orphans, al-Haytami issues a fatwa outlining a structure of maktab education that prevented any physical or economic exploitation of enrolled orphans.[6]

In the 11th century, the famous Persian Islamic philosopher and teacher, Ibn Sina (known as Avicenna in the West), in one of his books, wrote a chapter dealing with the maktab entitled "The Role of the Teacher in the Training and Upbringing of Children", as a guide to teachers working at maktab schools. He wrote that children can learn better if taught in classes instead of individual tuition from private tutors, and he gave a number of reasons for why this is the case, citing the value of competition and emulation among pupils as well as the usefulness of group discussions and debates. Ibn Sina described the curriculum of a maktab school in some detail, describing the curricula for two stages of education in a maktab school.[2]

Primary education

Ibn Sina wrote that children should be sent to a maktab school from the age of 6 and be taught primary education until they reach the age of 14. During which time, he wrote that they should be taught the Qur'an, Islamic metaphysics, language, literature, Islamic ethics, and manual skills (which could refer to a variety of practical skills).[2]

Secondary education

Ibn Sina refers to the secondary education stage of maktab schooling as the period of specialization, when pupils should begin to acquire manual skills, regardless of their social status. He writes that children after the age of 14 should be given a choice to choose and specialize in subjects they have an interest in, whether it was reading, manual skills, literature, preaching, medicine, geometry, trade and commerce, craftsmanship, or any other subject or profession they would be interested in pursuing for a future career. He wrote that this was a transitional stage and that there needs to be flexibility regarding the age in which pupils graduate, as the student's emotional development and chosen subjects need to be taken into account.[3]

Literacy

In medieval times, the Caliphate experienced a growth in literacy, having the highest literacy rate of the Middle Ages, comparable to classical Athens' literacy in antiquity.[7] The emergence of the Maktab and Madrasah institutions played a fundamental role in the relatively high literacy rates of the medieval Islamic world.[8]

See also

- Madrasah, meant for higher education

- Maktab Anbar

References

- Team, Almaany. "تعريف و شرح و معنى كُتاب بالعربي في معاجم اللغة العربية معجم المعاني الجامع، المعجم الوسيط ،اللغة العربية المعاصر ،الرائد ،لسان العرب ،القاموس المحيط - معجم عربي عربي صفحة 1". www.almaany.com. Retrieved 2019-05-22.

- M. S. Asimov, Clifford Edmund Bosworth (1999), The Age of Achievement: Vol 4, Motilal Banarsidass, pp. 33–4, ISBN 81-208-1596-3

- M. S. Asimov, Clifford Edmund Bosworth (1999), The Age of Achievement: Vol 4, Motilal Banarsidass, pp. 34–5, ISBN 81-208-1596-3

- Team, Almaany. "تعريف و شرح و معنى كُتاب بالعربي في معاجم اللغة العربية معجم المعاني الجامع، المعجم الوسيط ،اللغة العربية المعاصر ،الرائد ،لسان العرب ،القاموس المحيط - معجم عربي عربي صفحة 1". www.almaany.com. Retrieved 2019-05-22.

- Francis Robinson (2008), "Review: Law and Education in Medieval Islam: Studies in Memory of Professor George Makdisi, Edited by Joseph E. Lowry, Devin J. Stewart and Shawkat M. Toorawa", Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Cambridge University Press, 18 (01): 98–100, doi:10.1017/S1356186307007912

- R. Kevin Jaques (2006), "Review: Law and Education in Medieval Islam: Studies in Memory of Professor George Makdisi, Edited by Joseph E. Lowry, Devin J. Stewart and Shawkat M. Toorawa", Journal of Islamic Studies, Oxford University Press, 17 (3): 359–62, doi:10.1093/jis/etl027

- Andrew J. Coulson, Delivering Education (PDF), Hoover Institution, p. 117, retrieved 2008-11-22

- Edmund Burke (June 2009), "Islam at the Center: Technological Complexes and the Roots of Modernity", Journal of World History, University of Hawaii Press, 20 (2): 165–186 [178–82], doi:10.1353/jwh.0.0045

- Maktab Encyclopædia Britannica