Oceanic core complex

An oceanic core complex, or megamullion, is a seabed geologic feature that forms a long ridge perpendicular to a mid-ocean ridge. It contains smooth domes that are lined with transverse ridges like a corrugated roof. They can vary in size from 10 to 150 km in length, 5 to 15 km in width, and 500 to 1500 m in height.

History, distribution and exploration

The first oceanic core complexes described were identified in the Atlantic Ocean.[1] Since then numerous such structures have been identified primarily in oceanic lithosphere formed at intermediate, slow- and ultra-slow spreading mid-ocean ridges, as well as back-arc basins.[2] Examples include 10-1000 square km expanses of ocean floor and therefore of the oceanic lithosphere, particularly along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge[3][4] and the Southwest Indian Ridge.[5] Some of these structures have been drilled and sampled, showing that the footwall can be composed of both mafic plutonic and ultramafic rocks (gabbro and peridotite primarily, in addition to diabase), and a thin shear zone that includes hydrous phyllosilicates. Oceanic core complexes are often associated with active hydrothermal fields.

Formation

Oceanic core complex structures form at slow spreading oceanic plate boundaries which have a limited supply of upwelling magma. These zones have low upper mantle temperatures and long transform faults develop. Rift valleys do not develop along the expansion axes of slow spreading boundaries. Expansion takes place along low-angle detachment faults. The core complex builds on the uplifted side of the fault where most of the gabbroic (or crustal) material is stripped away to expose mantle peridotite. They comprise peridotites ultramafic rocks of mantle and to a lesser extent gabbroic rocks from the Earth's crust.

Each detachment fault has three notable features: a breakaway zone where the fault began, an exposed fault surface that rides over the dome and a termination, which is usually marked by a valley and adjacent ridge.

However, the formation process through detachment faults has its limitations, such as the scarce seismic evidence that low-angle normal faulting do exist,[6] where the presumably significant offset along such faults, which transect the lithosphere at low angle should be involved with some friction. The rarity of eclogite in oceanic core complexes also casts doubt on the deep source in such domains. The abundance of peridotites in oceanic core complexes could be accounted for by a unique variation of ocean-ocean subduction at the junction of slow-spreading oceanic ridges and fracture zones. Analog models of subduction show that density contrast of more than 200 kg/m^3 between two juxtaposed lithospheric slabs would lead the underthrusting of the denser one to depth of circa 50 km, where remineralization of pyroxenes into garnets would increase the slab's density and drive it into the mantle, provided that the friction between the slabs would be low.[7] There is ground to presume that at slow ridge and fracture zone intersections, the density contrast of the juxtaposed slabs would exceed 200 kg/m^3, the friction between the slabs would be low, the thermal gradient would be ca. 100 deg. C/km, and with ca. 5% water contents, the drop of the solidus of basalt at relatively low pressure would enable the co-occurrence of serpentinites and peridotites, the abundant rock-types in oceanic core complexes.

Examples

Some 50 oceanic core complexes have been identified, including:

- Godzilla Mullion, part of the Parece Vela Rift in the Western Pacific Ocean between Japan and the Philippines was discovered in 2001. It is about 155 km long by 55 km across, and is the largest known ocean core complex in the world.[9]

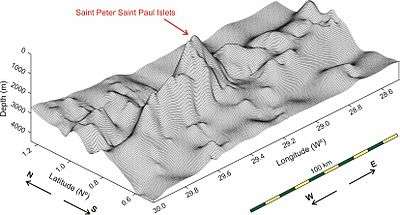

- The Saint Peter Saint Paul complex lies in the equatorial Atlantic Ocean. It is 90 km long and 4000 m high. The apex forms the Saint Peter and Paul Rocks. This is one of the few known examples where sea floor mantle rocks are exposed above sea level.

Research

Scientific interest in core complexes has dramatically increased following an expedition in 1996 which mapped the Atlantis Massif. This expedition was the first to associate the complex structures with detachment faults. Research includes:

- To investigate the structure of the mantle:

- The complexes provide cross sections of mantle material which could only otherwise be found by drilling deep into the mantle. The deep drilling that is required to penetrate 6-7 km through the crust is beyond current technical and financial constraints. Selective sample drilling into the complex structures are already underway.

- To investigate the formation of detachment faults

- To investigate the development of oceanic core complexes:

- In 2005 scientists from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute discovered a series of complexes in the North Atlantic, 1,500 miles (2,400 km) from Bermuda.[3] These structures are at various stages in their evolution—from bumps that indicated the emergence of a core complex to the faded grooves of long-exhumed core complexes that had been eroded away over millions of years. Such features will enable scientists to see active detachment faults in operation and understand their development.

- To study mineralisation and the release of minerals from the mantle:

- A steeply sloping detachment fault which penetrates deeply can be a conduit for hot mineral-rich hydrothermal fluids to circulate towards the surface and build mineral deposits. These deposits can grow massive because detachment faults persist for hundreds of thousands of years. The Woods Hole Institution is studying one such site, called the TAG hydrothermal field on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge.

- To investigate marine magnetic anomalies:

- The conventional view that marine magnetic anomalies arose in the upper, extrusive layer of the oceanic crust requires a rethink because perfectly normal magnetic anomalies arise at core complexes, where the crust has been stripped away. This suggests that the lower part of the ocean crust contains a substantial magnetic signature.

See also

References

Notes

- Cann et al. 1997; Tucholke, Lin & Kleinrock 1998

- Fujimoto et al. 1999; Ohara et al. 2001

- Smith, Cann & Escartí 2006

- Escartín et al. 2008

- Cannat et al. 2006

- Scholz, C.H. (2002). The Mechanics of Earthquakes and faulting, 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mart, Y.; Aharonov, E.; Mulugeta, G.; Ryan, W.B.F.; Tentler, T; Goren, L. : 1081. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - Motoki et al. 2009, Fig. 5

- Loocke, M.; Snow, J.E.; Ohara, Y. (2013). "Melt stagnation in peridotites from the Godzilla Megamullion Oceanic Core Complex, Parece Vela Basin, Philippine Sea" (PDF). Lithos. 182–183: 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.lithos.2013.09.005.

Sources

- Cann, J. R.; Blackman, D. K.; Smith, D. K.; McAllister, E.; Janssen, B.; Mello, S.; Avgerinos, E.; Pascoe, A. R.; Escartin, J. (1997). "Corrugated slip surfaces formed at ridge-transform intersections on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge" (PDF). Nature. 385 (6614): 329–332. Bibcode:1997Natur.385..329C. doi:10.1038/385329a0. Retrieved July 2016. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Cannat, M.; Sauter, D.; Mendel, V.; Ruellan, E.; Okino, K.; Escartin, J.; Combier, V.; Baala, M. (2006). "Modes of seafloor generation at a melt-poor ultraslow-spreading ridge". Geology. 34 (7): 605–608. Bibcode:2006Geo....34..605C. doi:10.1130/G22486.1. Retrieved July 2016. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Escartín, J.; Smith, D. K.; Cann, J.; Schouten, H.; Langmuir, C. H.; Escrig, S. (2008). "Central role of detachment faults in accretion of slow-spreading oceanic lithosphere" (PDF). Nature. 455 (7214): 790–794. Bibcode:2008Natur.455..790E. doi:10.1038/nature07333. hdl:1912/2805. PMID 18843367. Retrieved July 2016. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Fujimoto, H.; Cannat, M.; Fujioka, K.; Gamo, T.; German, C.; Mével, C.; Muench, U.; Ohta, S.; Oyaizu, M.; Parson, L.; Searle, R.; Sohrin, Y.; Yama-Ashi, T. (1999). "First submersible investigations of mid-ocean ridges in the Indian Ocean". InterRidge News. 8 (1): 22–24.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- MacLeod, C. J.; Searle, R. C.; Murton, B. J.; Casey, J. F.; Mallows, C.; Unsworth, S. C.; Achenbach, K. L.; Harris, M. (2009). "Life cycle of oceanic core complexes". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 287 (3): 333–344. Bibcode:2009E&PSL.287..333M. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2009.08.016. Retrieved July 2016. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Motoki, A.; Sichel, S. E.; Campos, T. F. D. C.; Srivastava, N. K.; Soares, R. (2009). "Present-day uplift rate of the Saint Peter and Saint Paul Islets, Equatorial Atlantic Ocean". Rem: Revista Escola de Minas (in Portuguese). 62 (3): 331–342. doi:10.1590/s0370-44672009000300011.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ohara, Y.; Yoshida, T.; Kato, Y.; Kasuga, S. (2001). "Giant megamullion in the Parece Vela backarc basin". Marine Geophysical Researches. 22 (1): 47–61. Bibcode:2001MarGR..22...47O. doi:10.1023/A:1004818225642.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Smith, D. K.; Cann, J. R.; Escartín, J. (2006). "Widespread active detachment faulting and core complex formation near 13°N on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge". Nature. 442 (7101): 440–443. Bibcode:2006Natur.442..440S. doi:10.1038/nature04950. PMID 16871215. Retrieved July 2016. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Tucholke, B. E.; Lin, J.; Kleinrock, M. C. (1998). "Megamullions and mullion structure defining oceanic metamorphic core complexes on the Mid‐Atlantic Ridge" (PDF). Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth. 103 (B5): 9857–9866. Bibcode:1998JGR...103.9857T. doi:10.1029/98JB00167. Retrieved July 2016. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)